For Abby Funseth, mother of one daughter with another child due in two months, a day without child care would be exhausting.

Funseth and her husband both work full-time, so finding a place to send their kids has always been a major consideration in how they’ve planned their family. Funseth said they talked to their daughter’s child care provider, Corrine’s Little Explorers in New Glarus, before getting pregnant with their soon-to-be second child.

“We told Corrinne when we were going to start trying, and she gave us a time frame for when she’d have a full-time spot open, and we tried to conceive a baby in a window when she’d have a full-time baby — and fortunately, it worked for us,” she said. “I love my job, and I knew I didn’t want to stay home permanently with my child, and so we had to find room for child care in our budget, and find space.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

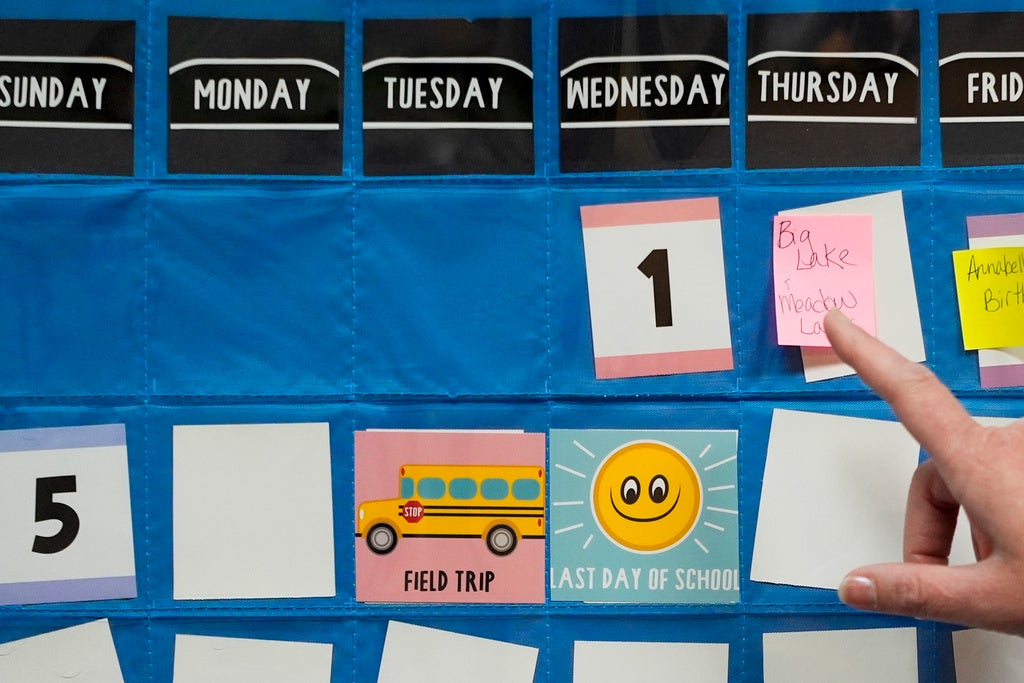

Child care providers around the country held a “Day Without Child Care” on Monday to raise awareness of how financially difficult it is to provide quality child care and pay workers a livable wage. Although the movement called for day care centers to close their doors for the day, several Wisconsin providers who participated in the event said they couldn’t bring themselves to close when they’d already had to leave families scrambling so many times in the past year because of COVID-19 closures.

“This was an incredibly hard year with children getting sick and then parents having to come take their kids home — and even if their kids didn’t get sick, we had to quarantine out rooms,” said Tracy Jensen, program director at Sunny Day Child Care in Washburn. “That was just a lot on parents to begin with, and we felt like there weren’t a lot of extra days parents could take off.”

Instead, Sunny Day gave parents a sheet to fill out describing what they would have to do without child care. One wrote that, as a single parent without family nearby who can help out, they’d have to continually call in sick to work. Another wrote that one parent in the family would have to quit working to watch the kids. Someone else wrote that they’d have to quit their job and find a lesser paid, work-from-home job.

The center is licensed for up to 192 kids but is at least four full-time positions short of the staffing Jensen said they need to be able to handle those kids comfortably. Right now, they’re managing by filling in for each other and carrying heavier loads.

In New Glarus, some providers pushed their opening time back to 11 a.m. and held a rally in a local park where providers, parents and community members talked about the need for more state and federal funds for child care.

The federal pandemic relief packages included funding for child care providers that helped them offer raises and bonuses to their staff, and some were also able to get Paycheck Protection Program loans. But the federal Child Care Counts grants are set to run out in 2024.

“What’s going to happen after that? Because financially, I won’t be able to sustain that,” said Tricia Peterson, director of Future All-Stars Academy in Juneau. “I hope to see more money come down through the early care and education programs directly to us.”

Peterson said she’s put all her relief dollars directly into bonuses and raises for her staff, and would like to pay them more. But staff alone already uses 88 percent of her budget, she said, and the center also has to cover overhead, snacks, insurance and everything else to create a healthy and safe learning environment for children. She criticized a statement U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson made in March, when he suggested mothers on public assistance should staff child care centers.

“Well, unfortunately, we have a lot of those working in child care — they’re on it because they can’t afford to — they don’t get paid very much, that’s why they’re on it,” she said.

Peterson said her pay scale is $11-15 per hour, and she’d like to see that raised to $15-25, but to do that, she’d have to raise her prices substantially, doubling the weekly cost of infant care.

Abby Funseth, the New Glarus mom, said that when her day care center closed for three months in the beginning of the pandemic, she was at first taken aback that the family still needed to pay for her daughter’s slot.

“I just didn’t understand why — why I needed to pay you when you’re not even watching my child and I’m here at home trying to work and watch my child,” she said. “What I realized was that there’s no support for day care providers outside of the paychecks they’re getting from their families, and it’s just not right.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.