The Wisconsin Supreme Court will hear oral arguments Tuesday in a redistricting lawsuit that seeks to declare Republican-drawn voting maps unconstitutional, a move that could shift the balance of political power that has existed in the state for more than a decade.

The redistricting lawsuit, filed by 19 Democratic voters from Wisconsin, was submitted one day after the investiture of liberal Supreme Court Justice Janet Protasiewicz, which gave liberals their first majority in 15 years. That timing, and comments made by Protasiewicz during her campaign that were critical of the maps, have spurred threats of impeachment from Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, underscoring the political stakes of redistricting as a tool used by Republicans to maintain power in the Wisconsin Legislature.

Democrats originally argued that existing Republican maps, which were adopted by the court’s former conservative majority in 2022, are an example of extreme partisan gerrymandering because they give the GOP an unfair advantage in State Assembly and State Senate races, stripping Democrats of political power in the process.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But the court’s four liberal justices decided not to take up the gerrymandering question directly. Instead, they focused on two others:

- Do the current maps violate the Wisconsin Constitution’s contiguity requirements for voting districts?

- Did the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision to enact Republican-drawn maps violate the Constitution’s separation of powers clause?

What is contiguity when it comes to redistricting?

Wisconsin’s Constitution states that when Assembly voting districts are drawn, they should be “bounded by county, precinct, town or ward lines, to consist of contiguous territory and be in as compact form as practicable.” It also states Senate districts should not split Assembly districts and should also be made of “convenient contiguous territory.”

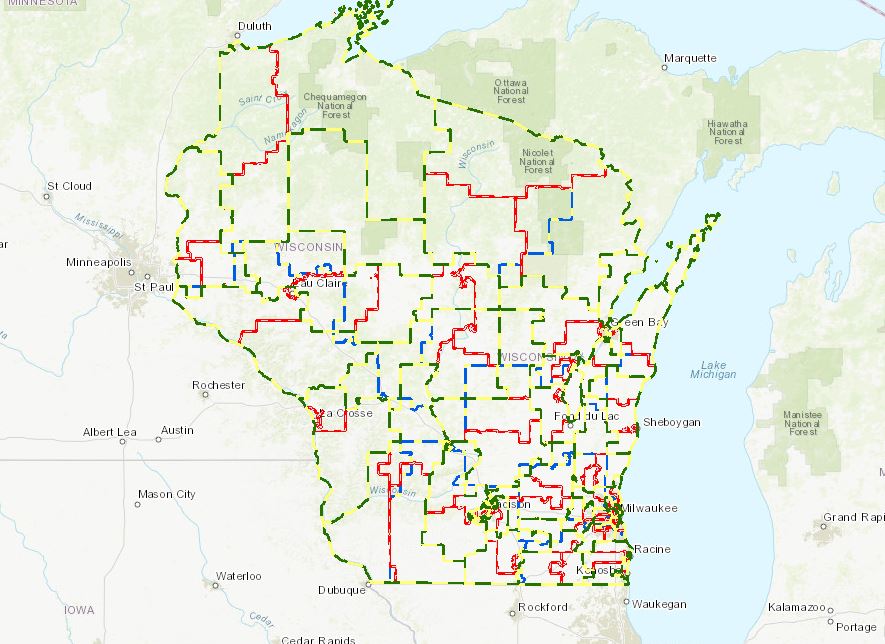

Attorneys representing the Democrats who filed the lawsuit argue that means all parts of the boundaries of voting districts should be physically touching. They provide examples of 55 Assembly districts and 21 Senate districts with disconnected pieces referred to as “islands.”

“Noncontiguity pervades both the assembly and senate maps — with noncontiguous districts across the entire state,” the Democratic lawsuit claims. “And this violation of the Constitution’s most basic redistricting requirement has representational consequences. Legislators are less likely — as the journal from the Constitutional Convention suggests — to interact with constituents residing in disconnected pieces of their district.”

Attorneys representing the Republican-controlled Legislature see the contiguity question differently. They argue the word “contiguous” in the Constitution has been interpreted by legislators, judges and justices to mean “politically contiguous municipalities” for more than 50 years.

“Petitioners’ ‘hyper-literal approach’— claiming ‘all parts of a district must physically touch such that a district may not have detached pieces,’ flouts precedent and plain meaning and is absurd and unworkable,” a brief from the Legislature claims. Republicans argue decades of annexations by municipalities necessitate the legislative “islands” and the issue is settled law because the Supreme Court, when deciding the cases that led to the current GOP maps, held that in those cases “the district containing detached portions of the municipality is legally contiguous even if the area around the island is part of a different district.”

University of Wisconsin-Madison Associate Professor of Law Robert Yablon is the co-director of the State Democracy Research Initiative and filed a brief with other scholars challenging the current maps. He told WPR the contiguity argument presented by Democrats is “rooted in the original meaning and practice of the Constitution.”

One case cited in both Democratic and Republican briefs goes back to 1992. Former Supreme Court Justice David Prosser, who was then a Republican legislator, filed a lawsuit challenging voting maps drawn by Democrats who controlled both houses. Those Democratic maps considered “islands” as contiguous. Prosser and Republicans argued for “literal contiguity.”

As circumstances have changed, the parties’ arguments have flipped. Yablon said the contiguity question is one that doesn’t have clear ideological lines.

“And so I suppose it’s not surprising that, over time, the political sides that have argued it one way or the other have changed depending on what they viewed as their interests at the moment,” Yablon said.

The ‘Separation of Powers’ argument

The Democrats’ lawsuit also argues the Supreme Court’s former conservative majority violated the state Constitution when it chose the maps drawn by Republicans after those maps were vetoed by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers. Legislators never held a vote to override the governor’s disapproval, Democrats note, but the Supreme Court enacted the maps anyway.

“First, the Court usurped the exclusive gubernatorial power to approve (or reject) a law passed by the Legislature,” Democratic attorneys claim. “Second, the Court exercised the exclusive legislative power to override the Governor’s veto. The current legislative maps unconstitutionally transgress the Constitution’s separation of powers and must be enjoined.”

Unsurprisingly, Republican lawmakers see things differently. They say that argument “fundamentally misunderstands” the court’s role in finding a judicial remedy when the Legislature and the Governor couldn’t agree on new voting maps in 2021.

In those legal battles, Republicans say, the court adopted a “least change” approach to ensure new maps comply with legal requirements without “rewriting duly enacted law.”

“Petitioners’ view would have the perverse effect of excluding the Legislature from redistricting remedies,” the Legislature’s brief said. “That cannot be justified by any constitutional theory, least of all separation of powers. The Constitution vests the Legislature with the power to redistrict.”

Loyola Marymount University Law School Professor Justin Levitt told WPR it’s not unusual for courts to use a “least change” approach when tasked with deciding voting maps after the legislative process breaks down. He said courts often ask for proposed maps from parties in a redistricting lawsuit.

But Levitt said there was a “fairly rare” twist when, in 2021, the Wisconsin Supreme Court asked parties for “least change” maps and Wisconsin Republicans offered Justices the exact same map that Evers vetoed.

“There are usually tweaks when the Legislature doesn’t have to worry about the governor or when the governor doesn’t have to worry about the Legislature, when other parties don’t have to worry about getting things through the legislative process, they put forward maps that look a little bit different,” Levitt said. “That didn’t happen here.”

Because of that, Levitt said, he’s not aware of any “great examples of precedent” in Wisconsin or elsewhere for the Supreme Court to follow with regards to the separation of powers question.

What experts are watching for

Levitt and Yablon say they’ll be watching for different things when attorneys argue before the newly-minted liberal majority of the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

Yablon said he’s curious about how the court’s more conservative justices handle the question of contiguity because it’s the type one would expect “more conservative members of the court would find attractive.”

“It’s a historically-oriented argument and looks to the original meaning of the Constitution and to 19th century practice,” Yablon said. “And so, is it something that they will have any sympathy for or not?”

On the question of separation of powers, Yablon has joined other legal scholars in filing a brief that argues the court’s previous conservative majority got it wrong when justices adopted maps that Evers vetoed.

Levitt said he’ll be looking to see how much “the popular image” of what the case is about seeps into legal arguments.

“The public thinks this is about partisan gerrymandering,” Levitt said. “And the court has been very clear, that’s not what it’s deciding.”

Levitt said he’s also not sure “how big the stakes are” with regard to the specific legal questions justices are asked to resolve. He said, in theory, both of those questions could be resolved with “pretty small changes.”

But things have changed since the last time this map was before the court. Republicans now hold a two-thirds majority in the Senate and are two votes shy of that threshold in the Assembly, which would give them the power to override a governor’s veto. And the court, which was run by conservatives last time around, now has a liberal majority.

“And so, the practical payoff is a very big deal indeed,” Levitt said. “Because it’s unlikely that the remedial map, if there is a remedial map, would look just a tiny bit different from the map that you’ve got in front of you.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.