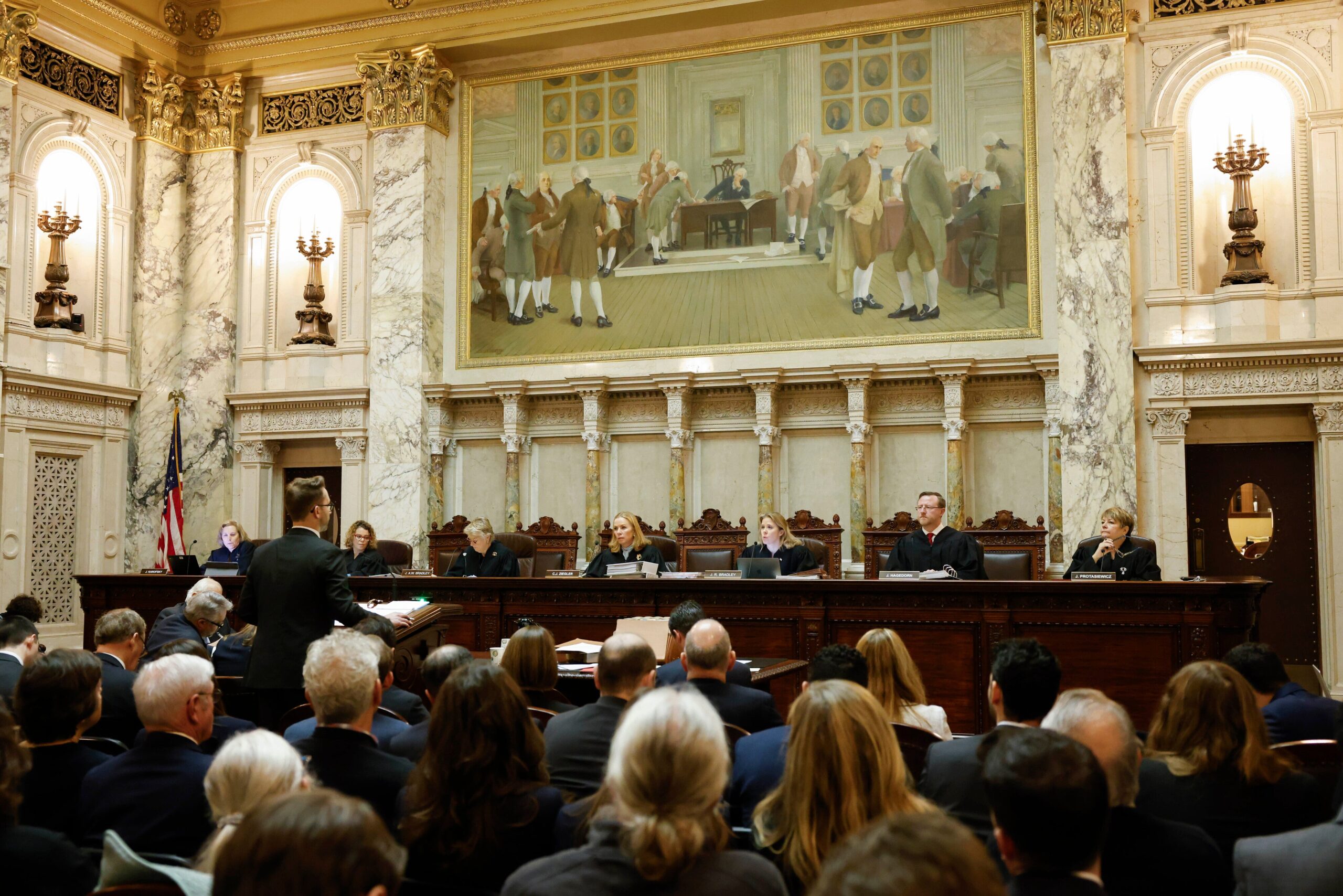

When the Wisconsin Supreme Court chooses a new redistricting plan to replace the state’s current, Republican-drawn maps, justices on the court’s liberal majority have said they’ll consider its “partisan impact.”

The term may sound mundane, but this is the first time it’s been used by the state Supreme Court in the modern era of redistricting, and how it’s defined could have big implications for the balance of political power in Wisconsin for years to come.

When the court’s 4-3 liberal majority issued its bombshell ruling Dec. 22 striking down Republican drawn voting maps, it laid out a list of criteria it wanted parties to the state redistricting lawsuit to use when drawing new districts. Those maps are due to the court by 5 p.m. Friday.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Aside from Constitutional requirements that districts be as compact as possible, include similar populations and have boundaries that physically connect, the majority opinion said justices will weigh partisan impact as one of their criteria.

“As a politically neutral and independent institution, we will take care to avoid selecting remedial maps designed to advantage one political party over another,” the majority opinion said. “Importantly, however, it is not possible to remain neutral and independent by failing to consider partisan impact entirely.”

Liberal justices said that by ignoring any potential partisan impact of maps proposed by parties like the Republican-controlled Legislature or Democratic Gov. Tony Evers, it could wind up enacting new districts that give an advantage to one party over the other.

The initial task of deciding whether proposed maps comply with the partisan impact criteria and others will fall to University of California, Irvine Political Scientist Bernard Grofman and Carnegie Mellon University Political Scientist Jonathan Cervas. The two were hired as consultants to the court and have been tasked by the majority with drawing their own maps if those submitted by parties come up short.

The court’s conservative justices scoffed at the partisan impact guideline in their dissents, accusing their liberal colleagues of failing to define the term in order to enact maps that benefit Democrats. Justice Rebecca Bradley went so far as to say the majority will consider partisan impact “without authority” rooted in the state constitution.

“The majority’s decision to consider the “partisan impact” of proposed maps lacks any legal foundation, enabling the majority to engage in a purely political exercise,” Bradley said.

Two ways to approach fair maps

Marquette Law School Lubar Center Research Fellow John Johnson, an expert on redistricting and how maps advantage political parties, told WPR there are two main ways to approach drawing a fair map.

The first is to ignore election results entirely when district lines are drawn.

“If you do that in Wisconsin, you’ll end up with a map that favors Republicans, because Republicans and Democrats are not spread out around the state in the same way,” Johnson said.

While Wisconsin’s electorate is split roughly 50-50 on a statewide level, Democratic voters are generally clustered in larger cities, said Johnson, while Republican voters are more spread out in small towns and rural areas. If partisanship isn’t considered by mapmakers, he said, “you’ll end up with a little bit of a gerrymander without even meaning to.”

Under the other approach to fairness, Johnson said, mapmakers try to draw districts using data on partisanship that are more competitive “or with a balance of districts that is closer to the balance of Democrats and Republicans in the state.” He said that’s what the court’s majority is doing.

Still, Johnson said, that means partisan impact will have to be weighed against other redistricting criteria, like requirements that districts be compact, of roughly equal population and contiguous.

“So I think the question is, what do you give up on one goal to get more of what you want on a different goal?” Johnson said.

Harvard Law School Professor Nicholas Stephanopoulos, who is one of the attorneys representing Democrats who brought Wisconsin’s redistricting lawsuit, told WPR there might be some tensions between the court’s criteria for drawing new maps.

“But when you start with a really pretty awful map,” Stephanopoulos said, “it’s often possible to improve on every dimension simultaneously.”

Stephanopoulos said he wouldn’t be surprised if new maps picked by the court “are much more fair” than those picked by the Supreme Court’s former conservative majority, while meeting the state’s constitutional requirements.

As for claims that the state constitution doesn’t authorize the court to consider partisan impact, Stephanopoulos said that same constitution also doesn’t authorize the “least change” approach used by the court’s former conservative majority in 2022 to enact the Republican-drawn maps that were struck down last month.

“This was a completely, court-made-up principle that had the obvious effect of continuing one of the most extreme gerrymanders in modern history,” Stephanopoulos said.

Once new proposed maps are submitted to the court, consultants Grofman and Cervas will weigh them against the court’s criteria and write a report by Feb. 1. If they determine that none of the maps meet that criteria, they’ll draw their own map and submit that for the court’s consideration.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.