The Supreme Court of Wisconsin is considering whether a man who was wrongfully convicted is entitled to know why the state’s Claims Board limited the compensation for his years in prison to $25,000 dollars.

Derrick Sanders was first convicted in 1993 on charges of first degree intentional homicide as party to a crime. According to the Claims Board’s 2019 decision, Sanders and two other men beat Jason Bowie in November 1992. One of the other men then took Bowie to a different location and killed him with a single gunshot to the head.

Under state law, anyone who is involved in “the commission of a crime,” either through assisting the person who commits the crime or conspiring with that person, can be convicted as a party to the crime.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

According to the Claims Board decision, Sanders consistently maintained that he was not involved in or aware of the shooting. He said his attorney didn’t properly explain what “party to a crime” meant, which led him not to contest the charges. He later appealed and the state Court of Appeals vacated his plea in 1995.

But Sanders said his new attorney had him enter the same plea in a new trial in 1996 and led him to believe that because he was a part of the beating, he was liable for the homicide. That plea was eventually vacated by a circuit court in August 2018, and prosecutors dismissed the charges against Sanders the following month after the person who shot Bowie reiterated in an interview with investigators that he acted alone.

In petitioning the state’s Claims Board, Sanders requested the maximum reimbursement available for the wrongful conviction of $25,000 and an additional $5.7 million in damages for his 26-year imprisonment. If the board approved of the additional damages, they would send a recommendation to the state Legislature.

But the Claims Board decided to award the $25,000 without addressing the request for additional damages in its decision. Sanders asked for a rehearing, saying the board had erred in not commenting either way on the claim. But the request was rejected.

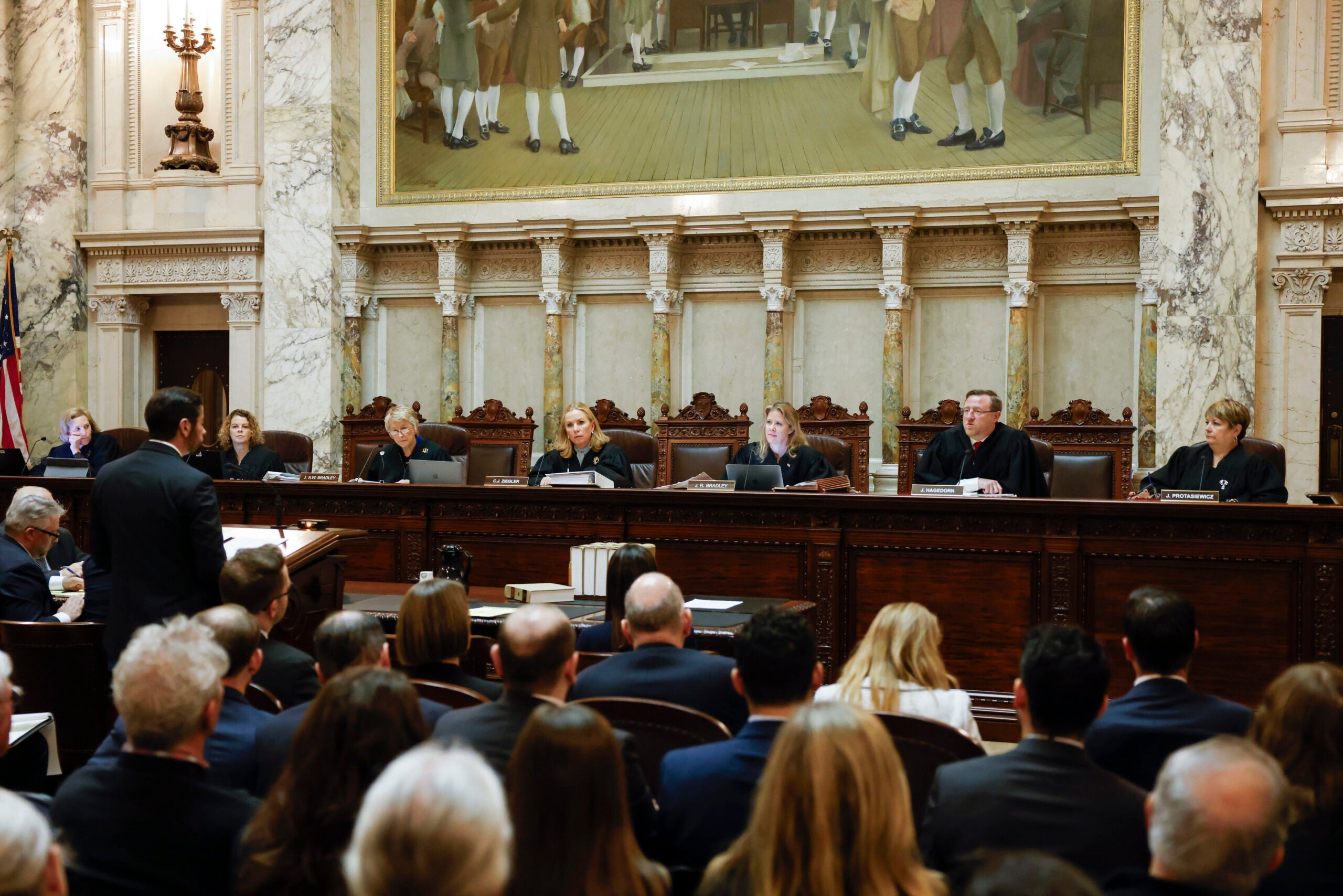

During oral arguments on Wednesday, Assistant Attorney General Colin Roth argued the board effectively decided that the $25,000 was the appropriate compensation for Sanders. He quoted from the letter denying Sander’s request for a rehearing, which said the board “did not conclude that the amount which it was able to award was not adequate compensation.”

“I know there’s a lot of negatives in that, but I think you can remove the double negative and simply bear a reading of that statement from the board as ‘we found that this was adequate,’” Roth said.

Matthew Splitek, attorney for Sanders, argued the board is required to offer some process of reasoning behind why they chose the compensation that they did.

“Whether it’s the maximum or not, they need to offer some explanation, so there is a process of reasoning evidenced in the record that the circuit court and, if necessary, the appellate courts can review,” he said.

Splitek asked the justices to return the case to the circuit court and ultimately the state Claims Board so that it can clearly state what equitable compensation should be for Sanders. He said it is up to the board to make that determination, regardless of whether the total exceeds the amount they are allowed to award.

But Roth argued that the Claims Board is not required to document its reasoning if it chooses not to make a recommendation for additional compensation. He said that recommendation is done in an advisory capacity to lawmakers, and is not something that can be reviewed by a court. Roth said any petitioner’s legal right to receive compensation for wrongful imprisonment only extends to the $25,000 cap outlined in the law.

“I think there’s no legal right at issue to more than $25,000. That’s the bottom line here,” Roth said. “The petitioner may have a right to money from the state, not a discretionary award from the legislature.”

But Justice Rebecca Dallet pressed Roth on the issue, saying the statute relates to people who have been wrongfully imprisoned by the state.

“What about the fact that this is someone’s liberty that was taken away by the state of Wisconsin wrongfully?” she questioned Roth, saying the statute is meant to give them the right to be appropriately compensated.

Several of the justices focused on the changes made between the original state statute from 1913 that created the board and a 1935 revision that introduced the $25,000 cap.

While Splitek argued the board’s charge to determine the appropriate compensation didn’t change under the revised language, Roth claimed the introduction of the cap limited the board’s findings to that maximum.

A decision in the case will be released by the end of the court’s session in June.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.