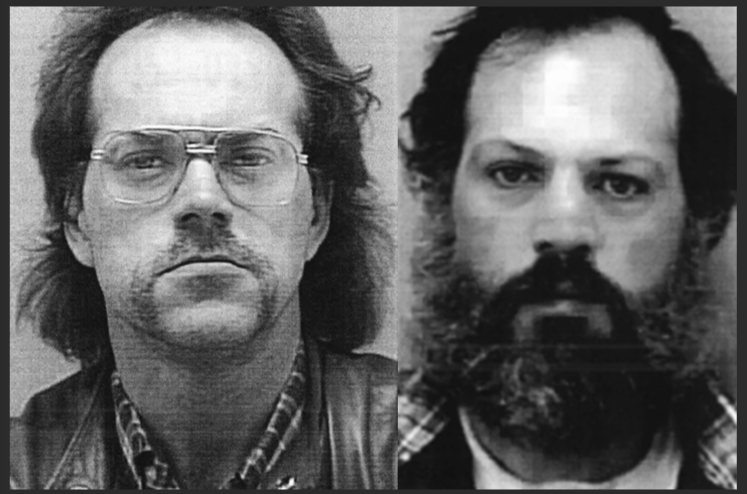

Two brothers from Green Bay got out of prison last year after serving more than two decades for a murder they didn’t commit.

Now, David and Robert Bintz could receive about $1 million each as compensation, if the state Legislature agrees to the payout.

In 1987, 44-year-old Sandra Lison went missing after shift at the Good Times bar in Green Bay. Her body was later found in the Machickanee Forest, and there was evidence that she had been robbed and sexually assaulted.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

That case remained cold for more than a decade, before the Bintz brothers were convicted of Lison’s murder in 2000.

But last year, a judge agreed to vacate their convictions after DNA evidence showed another man — who has since died — was actually guilty of raping and killing Lison.

State law caps compensation for wrongfully convicted people

Last week, the State of Wisconsin Claims Board agreed to reimburse the Bintz brothers for about $130,000 each in attorney’s fees.

The board also approved a payout of $25,000 to each brother. That $25,000 is the maximum amount possible under a decades-old state law that caps compensation to a wrongfully incarcerated person.

As Wisconsin Innocence Project Director Rachel Burg points out, it amounts to less than $3 dollars for each day the brothers wrongfully spent in prison.

“Which is less than what most of us spend on our daily coffee,” Burg said. “It’s a woefully inadequate amount.”

The Wisconsin Innocence Project represented David Bintz in the process. Robert Bintz was represented by the Great North Innocence Project, an affiliated nonprofit.

In its recently released findings, the Wisconsin Claims Board also recommended that the brothers receive an additional payment of $1 million each. Since that exceeds the cap set under state law, the additional amount would need to be approved by state lawmakers.

“No amount of money can ever give back David the time he lost,” Burg said of that recommendation. “We’re happy that they’ve acknowledged the harm that was done to him, but this is just a small step towards accountability for David and his brother.”

Jarrett Adams, the attorney who represented the brothers in the claims process, said he hoped the Legislature approves the board’s request sooner rather than later.

Robert is now 69 while David is 70. After decades behind bars, Adams said they have serious health issues and limited savings. In their claims filed with the state, each brother had initially requested about $2 million in compensation.

“Their life is a house of cards right now where they don’t really know where their resources will continue to come from,” Adams said.

Convictions were riddled with ‘red flags,’ Innocence Project attorney says

From the beginning, the case against David and Robert Bintz was riddled with a “lot of red flags,” Burg said.

“There’s a lot of hallmarks of wrongful convictions in this case, with things like jailhouse informants and alleged false confessions and forensic science issues,” Burg added.

After Lison went missing in the late ’80s, Robert and David were questioned by police. That’s after Robert and his friend bought a case of beer from the Good Times bar.

“Upon their return, David was allegedly angry and called the bar and yelled at Lison, as he was upset and believed the men were overcharged for the beer,” the claims board decision explains.

But, during that initial investigation, authorities tested blood and semen found on Lison’s clothes. That testing showed the genetic material could not have belonged to either of the Bintz brothers.

Things changed in 1998, while David Bintz was serving time in prison for the sexual assault of a child in an unrelated case. During that time, David’s cellmate told police that David had confessed to Lison’s murder while talking in his sleep.

After “over six hours of relentless interrogation,” David “allegedly made confused and contradictory statements, some of which implicated him and Robert in Lison’s murder,” according to claims board documents.

David Bintz has an intellectual disability, and during that interrogation he wasn’t allowed breaks for food or to use the bathroom, according to his attorney.

When the case went to trial, David Bintz later tried to maintain his innocence. Meanwhile, his brother, Robert, has always maintained his innocence, according to documents reviewed by the claims board.

Although police had initially been investigating the crime as a sexual assault, prosecutors switched gears when the Bintz brothers were charged.

Since testing had showed that the semen found of Lison’s clothes could not have belonged to either brother, the state argued that the genetic material could have come from a consensual sexual encounter before Lison’s death.

John Zakowski, who was Brown County’s district attorney when the Bintzes went to trial, did not respond to a request for comment from WPR. Zakowski is now a Brown County Circuit Court judge.

The Brown County District Attorney’s Office did not take a position on the Bintzes’ compensation claim. In filings submitted to the claims board, however, that office disputed the suggestion that David Bintz’s confession had been “coerced by relentless pressure” from detectives.

Who killed Sandra Lison?

In the mid 2000s, the Wisonsin Innocence Project used additional DNA testing to show that the blood on Lison’s dress belonged to the same man who left the semen found on her clothing.

David Bintz moved for a new trial based on that evidence but that request was denied.

“That (new information) should have been enough for their convictions to be vacated at that time, which would have saved the Bintz brothers a decade and a half of their lives,” Burg said.

Instead, it took until 2024 for the brothers to be released.

The Great North Innocence Project was eventually able to secure their release using the emerging field of forensic genealogy. That process has been made possible thanks in large part to the growing popularity of at-home DNA tests. It involves mapping out a genetic family tree and using the information to pinpoint or exclude suspects who have been tied to specific crimes.

Investigators used genetic mapping to tie Lison’s killing to one of three men who had been born to a Green Bay couple. One of those brothers, William Hendricks, had a previous conviction for a similar sexual assault. At the time of Lison’s murder, Hendricks was out on parole, and a car that looked like his had been spotted outside the Good Times bar on the night of Lison’s disappearance, according to documents submitted to the claims board.

The Innocence Project used that evidence to get a court order, allowing Hendricks’ body to be exhumed.

Analysis of those remains prompted the Wisconsin State Crime Lab to conclude that there was less than a 1 in 329 trillion chance that the DNA from the crime scene could have belonged to anyone other than Hendricks.

Hendricks will never go to trial for Lison’s murder. He died in 2000 — the same year the Bintzes were convicted.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.