While February’s Black History Month activities offer many a wider exposure to pivotal moments and people critical to understanding the African American experience, connecting with that history on a personal level can be more complicated. In particular, tracing African American family histories is sometimes challenging.

In recent years, sites like Ancestry.com or other resources and databases have made it easier for those seeking to explore their roots and understand their family genealogy. Even DNA testing has added a new dimension of scientific fact to test family lore.

But for African Americans interested in understanding the history of their families, the effort is more complicated. The legacy of slavery, prejudice and institutional racism mean many records are incomplete or aren’t easily available. As such, discovering information from popular genealogy sites can be difficult, especially before the 1870 U.S. Census. This is because this was the first census to include African Americans by name.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Despite the roadblocks, Laurie Bessler, a genealogy specialist in the Wisconsin Historical Society’s Library Archives and Museum Collections Division, said there are resources for those who want to know more.

Bessler, who has been researching family histories for nearly 40 years, spoke with host Kate Archer Kent on WPR’s “The Morning Show” to offer strategies for beginning the search.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: So it’s Black History Month, but for African Americans, tracing a family history can be really challenging. It can also be really painful. What kind of obstacles do African Americans encounter in this research?

Laurie Bessler: You know, I think one of the first things that they encounter is feeling like, “If I even try, I’m not going to find very much.” And it’s just not true. There’s so many records that could be found on everybody’s family history, but especially those groups that go into it thinking while they probably didn’t document much about my family, and yet they did.

KAK: Where should African Americans start when they want to trace their family history and really dig into this?

LB: Start with what you already have, and that is family stories, documents that your family may have kept, all of that. And then you put that information into charts, into family group sheets, into pedigree charts, so that it shows you what are you missing.

One of the key things that you have to watch for when you’re doing genealogical research is you need to know name, date and place, because a lot of the records you’re going to try and find will be relying on you knowing where are you going to have to try and find this record?

And of course, then the names that you’re researching and so on. Doing that research at home, talking to people first is really going to be key, especially again with those groups who may not have … as many documents out there. You’re really relying on the family history that came down through those lines and then it’s just really starting with that kind of thing. Then, when you go to the records, you’re working from the present to the past.

one of the records you’re really going to focus on … is you find them in censuses.

Now, the United States (has) done censuses from 1790 to the present. What we have available to look at is only from 1940 going back. So, if people know where their grandparents or their great-grandparents were in 1940, then you can leapfrog every 10 years going back to 1940, then back to 1930. And what you’re seeing are listings of families. So, once you find your great-grandfather in the 1940 census as a 5-year-old, then you can say, ‘OK, well, he’s living with his parents or his aunts and uncles or whoever he’s living with.’ You’ve identified more people to put on that tree.

KAK: You point out that there isn’t a single narrative for African Americans. (You said it) can’t be assumed that all African Americans were enslaved.

LB: Don’t look at the common narrative … look (and) you let the record show you your story.

So when you find you’ve gone back, like in the example I was giving in the censuses, and you actually find one of the family members who’s African American who shows up in the 1860 census, that means they were a free person because that’s the only people they list in the 1860 census.

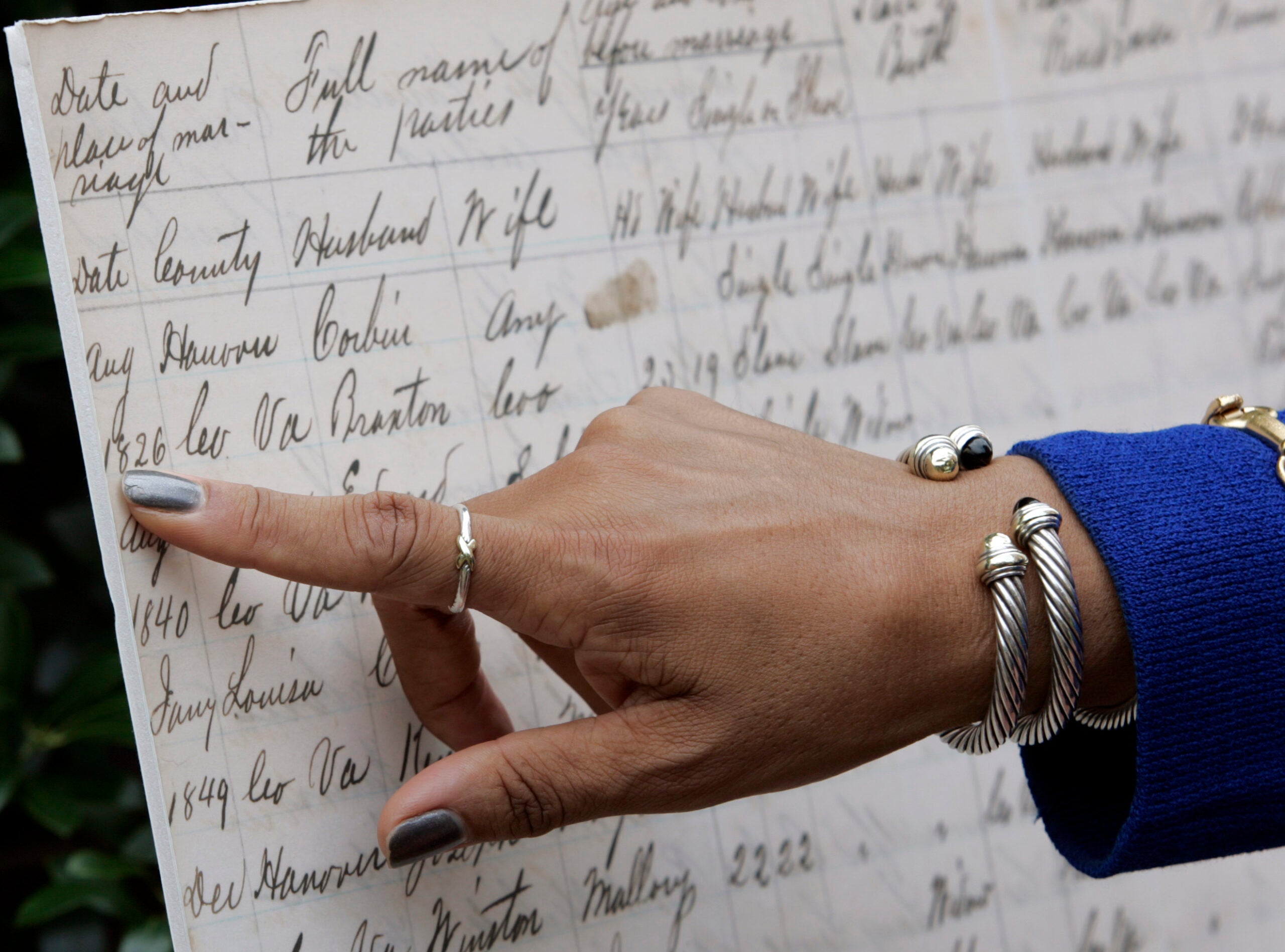

One of the main strategies that you use when you’re dealing with people who had been enslaved is that you look at the slaveholders’ history, their paper trail, their journals, their diaries. But most importantly, their probate files because a lot of times, slaves are listed in those probate files.

Now, plantation records are a little bit more difficult to find. There is a big series we have on microfilm in the library in the Wisconsin Historical Society called the Antebellum Plantation Records. And so, they cover many plantations throughout the South, but not all.

Wills and probate can actually be fairly easy to find. I call them land deeds, but they’re really property deeds. And so, when a person is transferring the property ownership of a slave from one person to another, I’ve seen one where a slave was transferred between two sisters and there was a deed that explains that transfer.

KAK: Aside from government records and other official census data, what are other big resources that we might not think about when researching African American history?

LB: They have a lot of local historians doing a lot of wonderful work. OK, so you have identified where your family is located in whatever state and whatever county at whatever time. You should be checking to see if any county histories have been written. Any documentation like everybody buried in this one cemetery could be a book that is out there as well as something that might be online.

And so looking at those local history collections now at the Wisconsin Historical (Society), we have been collecting these types of resources since the 1850s. So, we have a really wonderful collection.

KAK: How important are old newspapers?

LB: Newspapers are incredibly important … it’s telling us what’s going on in that community. It’s also one of the important things when you’re doing genealogical work, when you’re starting with the current generations and moving backwards. You’re going to look for them in every census. You’re going to find every birth, marriage and death records you can on each person in the family, because these have lots of clues. But you’re also going to find their obituary in the newspapers.

KAK: If you’re researching your family tree and you seem to hit a dead end, you just can’t get around it. What do you suggest that you do?

LB: I suggest people call us at Wisconsin Historical Society because we can have a consultation. I do phone consultations with people across the country. And so, what I do is I talk to them and say, “OK, what have you found? Where did you find that? Where did you look if you didn’t find something?” And I can explain the process.

And so, helping them come up with a research plan. There’s only been one time in my 20-plus years of doing this that I could not find another place for someone to look.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.