Pastry chef Noreen Ovadia Wills is whisking eggs in the kitchen of Coco Café on a Sunday morning in May in Washburn. The place is packed with customers eating baked goods and breakfast. It’s a common sight, and has been since she and her husband opened the business back in 2009.

Just six years before opening Coco Café, Wills said her drinking had made her unemployable.

“I went through this whole long period where I tried to control my drinking,” she said. “I was in and out of detox and treatment.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Wills started drinking heavily when she was 18 after she graduated from high school. She wound up in the restaurant industry by accident when she dropped out of college at the age of 22. Wills ended up moving to Lake Superior’s popular tourist destination Madeline Island in the summer of 1990. It’s where her love affair with food began, along with her spiral into alcohol abuse.

The island became a place she could fly under the radar as a person with alcoholism, discovering early on that she could line cook while drinking. Wills recalled one instance where the owner of the Beach Club, a popular bar and restaurant on the island, fed her Bloody Mary’s on the job.

“This is restaurant culture in a lot of places you go. You work hard, you get really sweaty and you go out drinking afterwards,” said Wills. “That’s not just Madeline Island. That’s basically a lot of places. It’s not just Wisconsin.”

A 2015 report from the Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality shows the accommodations and food service industry is among the top three sectors with the highest rates of heavy alcohol use next to mining and construction.

Dr. George Koob, director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, said it’s no surprise excessive drinking can lead to problems on the job.

“It doesn’t take much of an imagination to realize it contributes to injuries, fatalities, absenteeism, hangovers,” he said. “You’re not at your best. You’re slower to work. You make more mistakes.”

The most recent study available shows excessive drinking in Wisconsin cost $6.8 billion in 2012 — nearly 43 percent of that was due to lost productivity.

Employee Assistance Programs And Their Effectiveness

As workplaces became increasingly industrialized during the early part of the 20th century, alcohol-related accidents began to rise. This led companies to develop drug- and alcohol-free workplace policies, as well as programs to help employees struggling with alcohol.

Around 81 percent of employees work for an employer that has a written policy on alcohol and drug use, while 59.5 percent have access to an employee assistance program (EAP), according to a 2014 report from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

An EAP is a voluntary and confidential, work-based program that offers counseling, referrals and resources to employees dealing with work-place or personal problems like mental health issues and substance abuse disorders.

The foundation of EAPs is to improve job performance, said Dr. Paul Roman, regents professor of sociology at the University of Georgia. He said the idea is employees can seek out the services voluntarily, but sometimes employers will refer workers to the programs when their job performance begins to suffer.

“For a lot of workers, male and female, the job is really central to their identity, and it may be enough of a shock or wakeup call that they’re letting their behavior become sloppy that they don’t need to go to treatment,” said Roman.

Roman said EAPs have great potential to help workers. However, he questions whether other programs offered by companies are effective for addressing alcohol.

Much of the research about the impact programs have on employees struggling with alcohol is outdated in its assessment of outcomes and the rates at which programs are utilized. One 2003 study shows 62 percent of 1,050 people in 1999 who used an EAP for a wide variety of factors — not just substance use — avoided lost time from work. On average, work time that was not lost amounted to two work days when employees participated in the program.

Another 2016 study that examined 156 public employees who used EAPs in Colorado found they greatly reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety, but not at-risk alcohol use. Study author Melissa Richmond with the OMNI Institute said one factor may have been the low prevalence of employees who sought services related to alcohol. She said underreporting may also play a role.

“Sometimes when there’s no tolerance policies and even though in the consent process they assured people that their information would not be shared with their employers, we don’t know if underreporting might have contributed to our findings,” Richmond said.

Meanwhile, Roman noted a lot of EAPs are provided by outside private vendors that give people a 1-800 number to call where they may be referred to a handful of free counseling sessions.

“Then, after that, if that isn’t adequate then they supposedly have to start paying these counselors if they want to get anymore treatment,” Roman said. “That’s it. That’s all there is.”

“The company has to be behind the program. The program has to be of quality. And the employee has to be brave enough to ask for the help and it takes courage to ask for help.”

Clinical social worker Marina London

He said using outside providers can be a cost-saving measure for employers instead of providing a professional who works with employees in-house. However, licensed clinical social worker Marina London argues it’s difficult to maintain the perception of confidentiality when employers offer a professional within the workplace.

London, who works for the Employee Assistance Professionals Association, adds a variety of factors also play a role in whether employees use such programs ranging from awareness they exist to circumstances in the employee’s life. She said a good EAP has behavioral health professionals who provide confidential services to help connect people with the resources they need.

“The company has to be behind the program,” London said. “The program has to be of quality. And the employee has to be brave enough to ask for the help and it takes courage to ask for help.”

London said employees could receive reasonable accommodations under the Americans with Disability Act. Workers might also be able to take family and medical leave to seek treatment. Still, there are a variety of reasons that keep people from asking their employer for help.

Barriers To Seeking Help

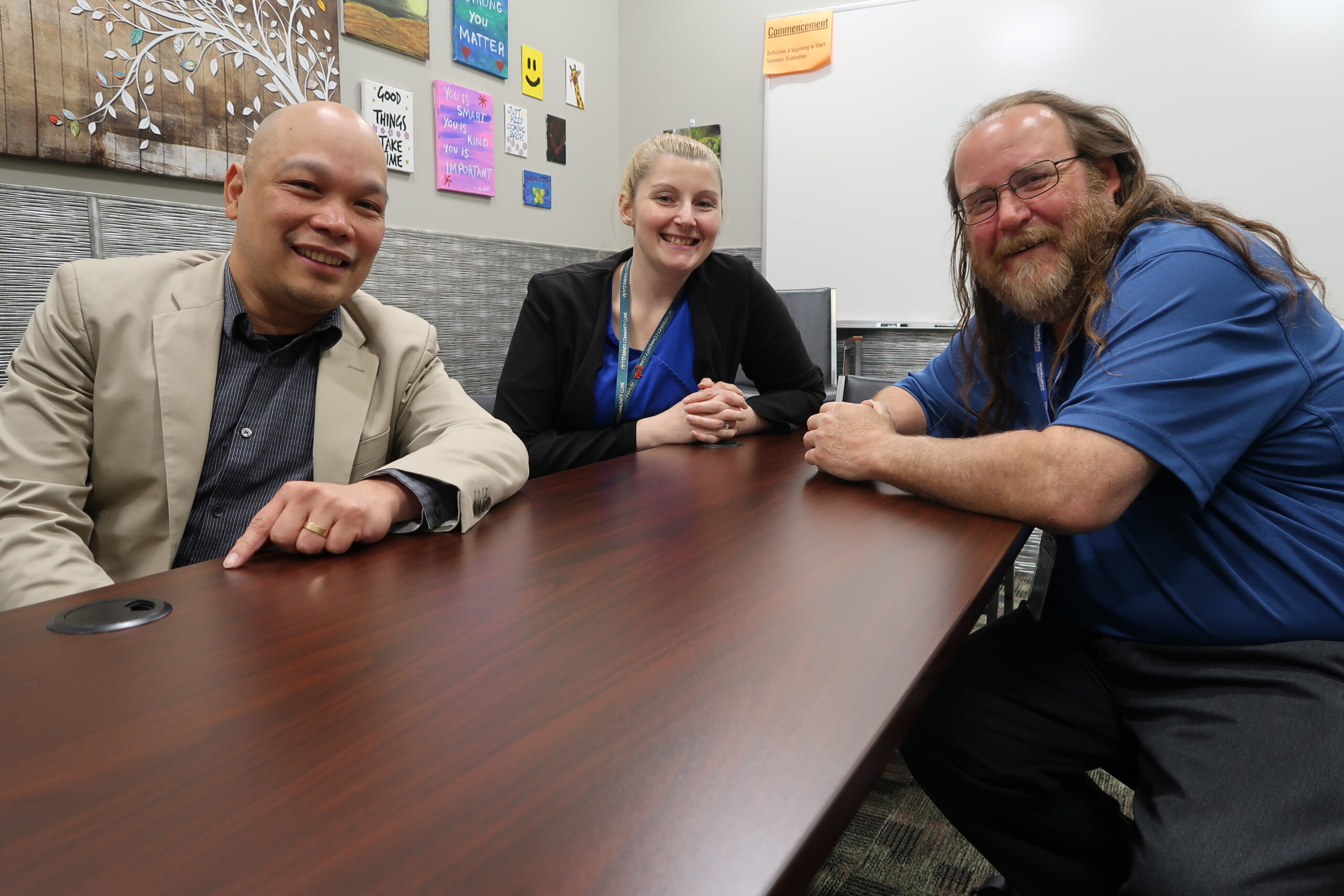

Terry Schemenauer sits at an alcohol- and drug-free drop-in center in Ashland. He’s on the board of the nonprofit coalition Partners in Recovery, which seeks to help addicts and alcoholics get resources they need in northern Wisconsin.

Schemenauer, a recovering alcoholic, recalled working construction many years ago and closing down the bars after work. He said one reason people might shy away from seeking help is the stigma associated with substance abuse.

“Alcoholism and drug addiction still have negative connotations,” he said. “It’s unusual for professional people to talk about this and come out and say, ‘Yeah, I’m in recovery.’”

Others may not have health coverage or fear backlash from their employer.

Pete Wasson, a newspaper editor and board member with Partners in Recovery, said his boss was very understanding the first time he checked himself into treatment while working for a newspaper in New Richmond, Indiana. Wasson said the newspaper held his job open for 28 days, but it wasn’t long before he relapsed.

“I would have an evening assignment … that I had to cover so I would cut out of work at noon and have a few drinks. I was still pretty drunk when I went to that evening assignment,” Wasson said. “Eventually, they got tired of my shenanigans.”

“Alcoholism and drug addiction still have negative connotations. It’s unusual for professional people to talk about this and come out and say, ‘Yeah, I’m in recovery.’”

Partners in Recovery board member Terry Schemenauer

Yet, for others, a stressful work environment may play a role in their alcohol use or prevent them from reaching out.

Recovering alcoholic Robert Fredericks works as a certified peer specialist with NorthLakes Community Clinic in Ashland, which offers addiction treatment in northern Wisconsin. He said a toxic work environment at a job in Madison sparked a relapse.

“I left work one day and went straight to the liquor store and for two weeks I was at the bottom of a whisky bottle. I looked in the mirror one day and said, ‘Don’t do it again, Bob,’” he said. “So, I packed up and I left and came back to my family and I started over.”

Now, Fredericks is counseling others who are in recovery.

Dr. Mark Lim, addiction medicine physician and recovery program medical director at NorthLakes, said a genetic disposition and a person’s mental health, along with their environment can play a role in activating the disease.

“(It’s the) exact same thing with diabetes. Sugar doesn’t make people diabetic. I could eat as much sugar as I wanted to, but it might not be healthy to me. It doesn’t mean I’m going to develop diabetes,” said Lim. “But, unfortunately, I have a genetic disposition. I could be diabetic. If I eat sugar, I don’t exercise, I don’t take care of myself, I might develop diabetes.”

Danielle Kaeding/WPR

Wills, who is adopted, said a history of the disease runs on her biological mom’s side of the family.

But, she said it never occurred to her to ask an employer or others for help because she wasn’t ready to admit she was struggling.

Around 38 percent of people who need treatment cite not being ready to quit as the reason they don’t reach out for help, according to SAMHSA.

“It helps to know where you can go for help when you need it. It doesn’t mean you’re going to get it,” she said. “It doesn’t mean you’re going to ask for it.”

When Wills did reach out for help, it wasn’t easy. She said she went to detox more than a dozen times and began going to recovery meetings. But, now, Wills has gone from being unemployable to hiring others looking for a second chance. She’s even driven employees to detox herself.

Wills said it may seem crazy, but someone was crazy enough to take a chance on her.