I recommitted to a meditation practice as part of my recovery from addictive behaviors. I really wanted to meditate with others, and I shared this desire with a friend. She’s an avid meditator who is also 12 years sober, and she knows firsthand how practicing meditation and mindfulness in recovery can help.

My friend soon invited me to my first in-person Recovery Dharma meeting. The meeting was at a yoga studio on Madison’s east side. While there are a handful of Recovery Dharma meetings around Wisconsin, Recovery Dharma “offers a trauma-informed, empowered approach to recovery based on Buddhist principles,” according to its website. It also offers free access to its Recovery Dharma handbook, guided meditations and other resources.

The meeting participants were kind and welcoming. The format was easy enough to follow. But I realized that a majority of the folks there didn’t look like me. I wondered if other people of color practiced meditation as part of their recovery.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

I went looking for an affinity space within Recovery Dharma. Affinity spaces are voluntary groups formed by folks who share common identities. I was looking for one exclusive to Black, Indigenous and/or people of color, or BIPOC.

Just as there are countless forms of meditation, and seemingly endless benefits, there are myriad reasons why affinity spaces are important to the success of institutions.

One of the most important is that affinity spaces foster psychological safety and belonging among their members. They serve as a “refuge” for traditionally underrepresented and marginalized people. Finding the right ones can be challenging because people have multiple, intersecting aspects to their identities. In regions of the country that are less racially and ethnically diverse, it is even more difficult.

For example, I identify as a cisgender woman who is both Black and queer. Research shows that offering culturally sensitive treatment options, ones that address racial, ethnic, and identity-related root causes of addiction, are essential to the ability of diverse groups of people building sufficient recovery capital, which are vital, interconnected resources that aid in maintaining a healthier lifestyle.

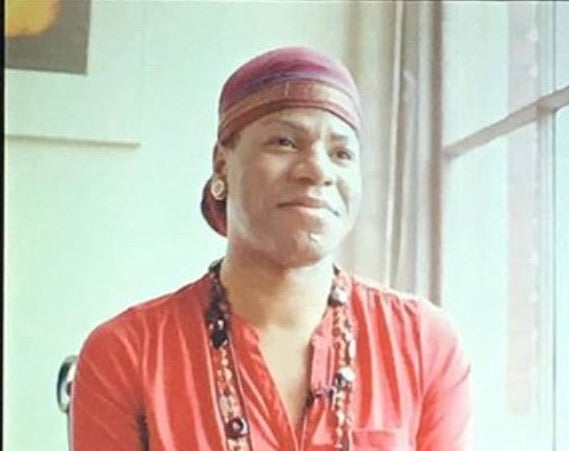

In my search, I was referred to Ablossi Tzaphkiel. Tzaphkiel identifies as two-spirit and Indigenous. They have a long history as a practicing Buddhist and were elected to the board of Recovery Dharma local in May 2025.

“I like Recovery Dharma because it’s not about being a Buddhist,” Tzaphkiel said. “We use a Buddhist practice to talk about our addiction, which is basically suffering that’s born out of running from and grasping.”

“In traditional recovery spaces, it’s ‘the men stay with the men, the women stay with the women,” and there’s a reason for that’. I did struggle a little bit because that wasn’t my story and that really wasn’t going to work with me. It’s difficult sometimes when I’m super open and vulnerable and the word I use is ‘open.’ Men don’t always hit the bullseye for me personally,” Tzaphkiel chuckled.

“I have different needs and I have a different experience and orientation,” Tzaphkiel added.

Later, after attending a few of the BIPOC Recovery Dharma meetings online, I met Sara Bumpus. Bumpus volunteers often in these sanghas, helping to pick the meditations and offer tech support at the meetings. On occasion, Bumpus also delivers a meditation of her own, inspired by phrases from the Recovery Dharma handbook.

“Take a moment to settle in, focusing on your breath, and allow me to read this love letter to you,” Bumpus said.

“Breathe in whatever way feels most comfortable and helpful to you right now. Knowing that your lungs are already doing the work, filling you with life. You are breathing with friends here, dear Sangha. There is nothing else that needs your attention right now. Feel into how powerful it really is that we’re all here together right now, just breathing. In different time zones, breathing together with intention. There’s something magical about this. Can you feel it?” she gently asked.

Her love letter brought tears to my eyes because it rang so true. There is something magical about people who experience great harm and trauma finding the strength to hold space for each other. While the work to end our individual and collective suffering as BIPOC folks in recovery is far from over, Recovery Dharma and the BIPOC sanghas offer restorative, validating, and meaningful support on the path.

Editor’s note: The full conversation with Ablossi Tzaphkiel, Sara Bumpus and Morgan D. Stewart can be found on the uHuman: a multimedia miracle website and podcast, which is exploring creative tools used to help people in recovery. Audio engineering support for this story was provided by Luke Tschosik, a music producer living in Madison, Wisconsin.

“Wisconsin Life” is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS Wisconsin. The project celebrates what makes the state unique through the diverse stories of its people, places, history and culture.