It may be the dead of winter, but a recent mapping campaign found heavily developed urban areas of Milwaukee stayed about 10 degrees warmer at night than other parts of the city during hot summer days.

Last summer, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources coordinated with groups and agencies to measure how extreme heat is affecting the city.

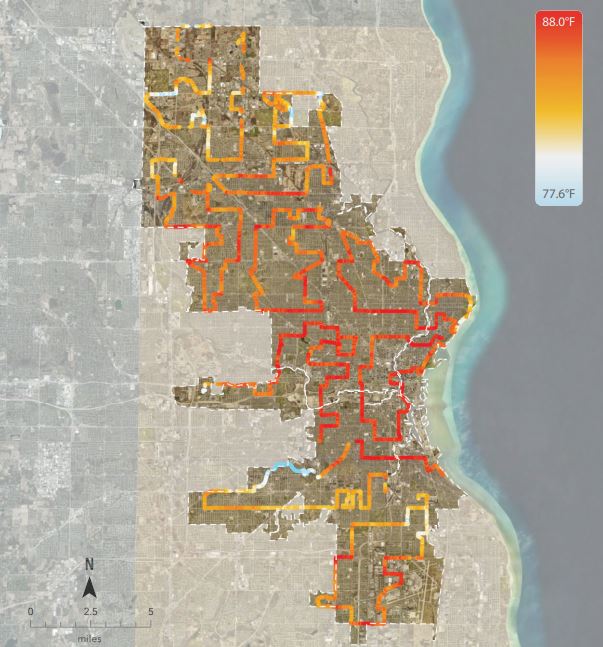

During July 21 and 22, a group of 43 volunteers drove vehicles donned with sensors around the city to collect temperature and humidity data every second for about an hour. They drove along nine routes during the morning, afternoon and night. Volunteers collected more than 59,000 measurements over 96 square miles of Milwaukee.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The results showed a 10-degree difference at night between the hottest and coolest areas of the city, according to Dan Buckler, an urban forest assessment specialist with the DNR. He said they found the hottest spots centered around the most heavily developed areas.

“In those parts of the city, which had fewer trees, fewer green spaces and more asphalt and concrete, they tend to keep being hot into the evening,” Buckler said. “So we saw that biggest differential in the evening.”

Volunteers recorded a maximum temperature of 96.7 degrees Fahrenheit during the day. The highest temperature at night was around 88 degrees on Brady Street in the city’s lower east side, while other parts of Milwaukee cooled down to 77.6 degrees. Buckler said downtown Milwaukee, the east side and lower south side of the city experienced the hottest temperatures.

Joey Williams, manager of climate services consulting firm CAPA Strategies, worked with the DNR on the data collection campaign in Milwaukee and 15 other cities last summer.

“We see that kind of spread with temperatures — that there’s more green space on the outer edges of the city, whereas you’ve got some denser land uses towards the core,” Williams said. “And that results in higher temperatures in the core and cooler on the outside, so that was very typical of what we expect to see.”

Asphalt and concrete absorb heat in a process referred to as the urban heat island effect. As climate change drives temperatures higher, the number of days with a heat index above 105 degrees in Milwaukee will likely triple by 2050.

That’s among the findings of Wisconsin’s Initiative on Climate Change Impacts. The latest report from the statewide collaboration of scientists and various groups found the number of nights at or above 70 degrees Fahrenheit will likely quadruple by mid-century.

Steve Vavrus, the initiative’s co-director and state climatologist, said heat doesn’t dissipate at night as easily during humid, summer days. Humidity in the air becomes like a blanket that prevents heat from escaping, and cities like Milwaukee that have more development retain heat even more. He said that can create dangerous conditions at times during heat waves.

“This has implications in terms of public health because studies have shown that nighttime heating, when the body’s unable to cool off at night, can be as deadly or deadlier than extreme daytime heat even with lower temperatures,” Vavrus said.

Image courtesy of CAPA Strategies

Extreme heat kills more people nationwide than any other weather event, according to most recent data from the National Weather Service. In 1995, a massive heat wave killed hundreds of people in the Midwest, including at least 85 people in Milwaukee. More recently, Wisconsin witnessed 27 heat-related deaths in 2012.

Vavrus noted the maps coordinated by the DNR and others strongly overlap with the Milwaukee heat vulnerability index created by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services in 2014. State health officials identified the inner core of Milwaukee among areas where people are most vulnerable to heat-related illnesses or deaths. The index found low-income residents and people of color are at higher heat risk in the center of the city and along highways.

“This is really troubling because it means there’s a double whammy. Places in the city that are the hottest are also the most vulnerable,” Vavrus said. “And, therefore, we need to really intensify strategies to try to find ways to allow those residents to cope better with extreme heat waves.”

Groundwork Milwaukee, a nonprofit group that promotes green infrastructure and climate safe neighborhoods, said they’ve already found a direct link between at-risk neighborhoods and redlining with their own GIS mapping in Milwaukee. Redlining refers to government maps developed in the 1930s that outlined areas with racial and ethnic minorities in red that involved discriminatory investment practices and prevented groups from owning certain properties. Redlined neighborhoods became generally concentrated near the center of urban areas, according to the nonprofit public policy group Brookings Institution.

“With the lack of trees, with redlining, and all of the socio-economic conditions that sprang from that, I’m not surprised at all that these neighborhoods run hotter than what they should be,” Young Kim, the group’s executive director, said.

Kim said they’re trying to share maps with residents so they can work with them on green infrastructure to mitigate the effects of extreme heat due to climate change.

“The time to plant trees properly is now. Trees not only provide shade, they beautify. They reduce noise pollution,” Kim said. “They also have a cooling effect, especially after it rains.”

The group is already working with neighborhoods like Metcalfe Park to design green spaces. Kim said there needs to be more planning around cooling centers, keeping houses cool with insulation and potential renewable energy development to ensure reliable power on days of peak demand.

Vavrus noted more trees and green spaces can make a difference over the long run. In the immediate future, public cooling centers and a program to provide free air conditioners are examples of ways to reduce risks for those facing extreme heat.

“A study like this can be helpful in allowing decision-makers to really target, with limited resources, how to apply those,” Vavrus said, “and making sure that the services that they can provide, in terms of cooling, go to the people who need it most.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.