Major utilities serving Wisconsin are moving forward with plans to increase solar and wind projects as they’ve set goals to drastically reduce carbon emissions over the next several decades. But some are making the transition to renewable energy faster than others.

Minneapolis-based Xcel Energy was the first major utility to announce its commitment to transition to 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2050. Madison-based Alliant Energy and Milwaukee-based WEC Energy Group, which owns We Energies and Wisconsin Public Service, have both pledged to cut carbon emissions 80 percent from 2005 levels by 2050.

The transition to renewable energy is being driven by declining costs, customer and investor demand and anticipated policy changes on carbon emissions.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

A larger portion of the utilities’ carbon-free energy mix has come from sources like wind or nuclear energy. The utilities had little to no investment in utility-scale solar as part of their energy supply. But in the last year, Xcel told regulators of its plans to add 3,000 megawatts of solar in the Upper Midwest.

WEC Energy Group, meanwhile, had received approval or was seeking 300 megawatts of solar generation in addition to up to 185 megawatts of solar pilot programs in Wisconsin.

Then, Alliant Energy announced plans earlier this month to add 1,000 megawatts of solar, although exactly where solar generation would be developed hasn’t yet been detailed.

Utilities say the declining cost of solar is one major factor prompting investment.

“It’s become much more cost-effective very quickly,” said Annemarie Newman, an Alliant spokeswoman.

“Now is the right time to be putting up and proposing these plans,” said Brendan Conway, spokesman for WEC Energy Group.

Xcel, which serves 241,000 electric customers in the state, provided about 25 percent of its energy from renewables last year with a goal of providing up to 60 percent renewable energy by 2030.

Alliant, which serves more than 450,000 electric customers, provided 20 percent of its energy from renewables last year with a goal of providing 33 percent renewables by 2024.

WEC Energy Group, which delivers electricity and natural gas to around 3 million customers in Wisconsin, had around 3 percent renewable energy through subsidiary We Energies last year and about 2 percent through Wisconsin Public Service. WEC Energy Group reported 52 percent of its energy came from low to no carbon sources in 2018, estimating around 71 percent of its energy will come from low- to no-carbon sources in 2030.

Environmental groups have pushed utilities to be more aggressive in shifting away from coal-fired generation and plants that emit fossil fuels as scientists are sounding the alarm on climate change.

Tyler Huebner, executive director of RENEW Wisconsin, said more than 6,000 megawatts of solar and around 1,200 megawatts of wind projects are being explored by private development firms in Wisconsin that could be utilized by utilities. As providers transition to renewables, a number of factors are driving the pace and level of investment, including regulatory uncertainty, technology, siting challenges and existing coal plants.

Huebner likened investments in existing power plants to a mortgage on a home.

“When you have these existing plants, they’re on a schedule to be paid off and you’re somewhere in the middle of that schedule,” said Huebner. “You don’t necessarily want to turn it off if you still have 25 years left to pay on the mortgage for that power plant. Then, you might have to pay the mortgage for a plant you’re not using plus something new.”

The transition could increase costs for ratepayers, which is something utilities and citizen groups are looking to prevent, according to Tom Content, executive director of the Citizens Utility Board.

“If we can reduce the price tag that’s going to be billed (to) customers for the plants they don’t want, that’s going to be critical for helping to pay for the cleaner sources they do want,” said Content.

Alliant has retired more than 30 percent of its coal generation plants since 2005. The company has around 1,000 megawatts of coal capacity remaining in Wisconsin.

“It will be a matter of looking at other technologies and what other capacities we have to capture renewable energy to make even greater use of that,” said Newman. “That’s something that we’re continuously monitoring.”

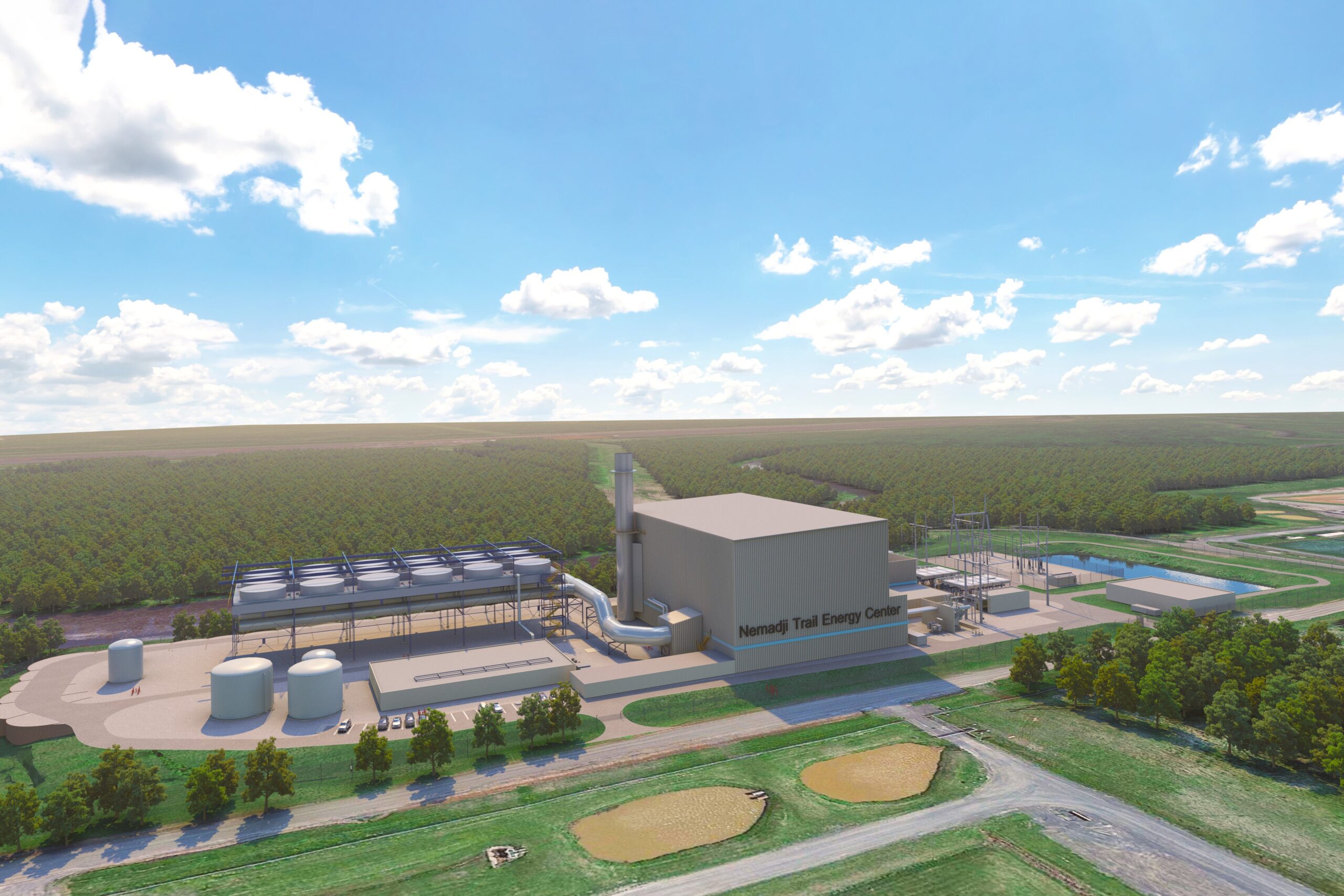

As it shifts away from coal, Alliant has added more natural gas to its system to maintain reliable electricity with more intermittent renewable sources, including a $700 million natural gas plant set to come online in early 2020.

WEC Energy Group has also transitioned to natural gas or shut down more than 2,800 megawatts of its coal generation in the last decade, including the Pleasant Prairie power plant that was shuttered last year. Conway said the closure is expected to save ratepayers $2.5 billion over 20 years.

Yet, he said there are no plans to close remaining plants in the near future, adding they’re constantly evaluating affordability and reliability of service as they transition to carbon-free energy sources. The company noted in its 2019 climate report that it’s considering other options like carbon capture and sequestration as it moves to reduce carbon emissions from plants built after 2000. In addition, it’s purchasing power from the Point Beach Nuclear Plant, which Conway said provides around one-fifth of their daily carbon-free energy mix.

“There is no kind of one-size fits all approach … We all are dealing with different things. We’re all dealing with different weather. We’re all dealing with different types of customers and even a regulatory environment,” said Conway.

Xcel expects to retire 23 coal-generating units by 2027, which is about half of its coal capacity. Mark Stoering, president of Xcel Energy for Wisconsin and Michigan, said utilities will have to consider all options to eliminate carbon emissions.

“Getting from 2030 to 2050 and getting that last 20 percent of carbon out of the system is going to take something else because gas still produces carbon,” said Stoering. “We see a system without gas-fired generation on it, but we’re going to need something else.”

Utilities will also likely need more transmission lines to tie renewable energy sources into the electric grid, which is expensive and complex. Although, environmental groups and citizens have pushed providers to pursue battery storage or other technology as opposed to infrastructure. Utilities argue storage is cost-prohibitive and volatile.

However, Greg Nemet, public affairs professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and affiliate with the Wisconsin Energy Institute, said the cost of batteries now looks like solar around a decade ago.

“It could be that it’s not an economical decision exactly now, but within a couple of years I think we’d be missing the boat if we’re not putting batteries in at least some parts of the grid,” said Nemet.

More regulatory certainty surrounding a potential federal price on carbon emissions or increased federal research and incentives may help accelerate the transition, according to Rolf Nordstrom, chief executive officer and president of Great Plains Institute, a Minneapolis-based nonpartisan nonprofit energy research group.

“If we enacted, both at the federal level and the state level, policies that made it clearer where we’re headed, I think that would be enormously helpful,” said Nordstrom. “It would help the business community be able to operate in a more predictable environment and know how to invest.”

If anything is certain, the transition to renewables and carbon-free energy will be an incredible lift, said Nordstrom.

“Worrying too much now on the front end about whether or not it’s 100 percent renewable or 70 to 80 percent renewable does not feel, to us, like energy that’s terribly well spent.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.