The Mark Hembree Band is well-known in Wisconsin’s bluegrass music scene. Its upright bass playing leader, Mark Hembree, has been playing music professionally for decades. For “Wisconsin Life,” WPR’s Norman Gilliland talked with the Oconomowoc musician about his time playing with another bluegrass legend, Bill Monroe.

==

While waiting for a friend outside the Stoughton Opera House, I struck up a conversation with a gent whose down-home Sunday attire was topped by a weathered Stetson.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Before long, we were talking about bluegrass — that confluence of African American blues, jazz, Irish ballads and dance tunes.

It turns out that one man is credited with inventing and naming bluegrass.

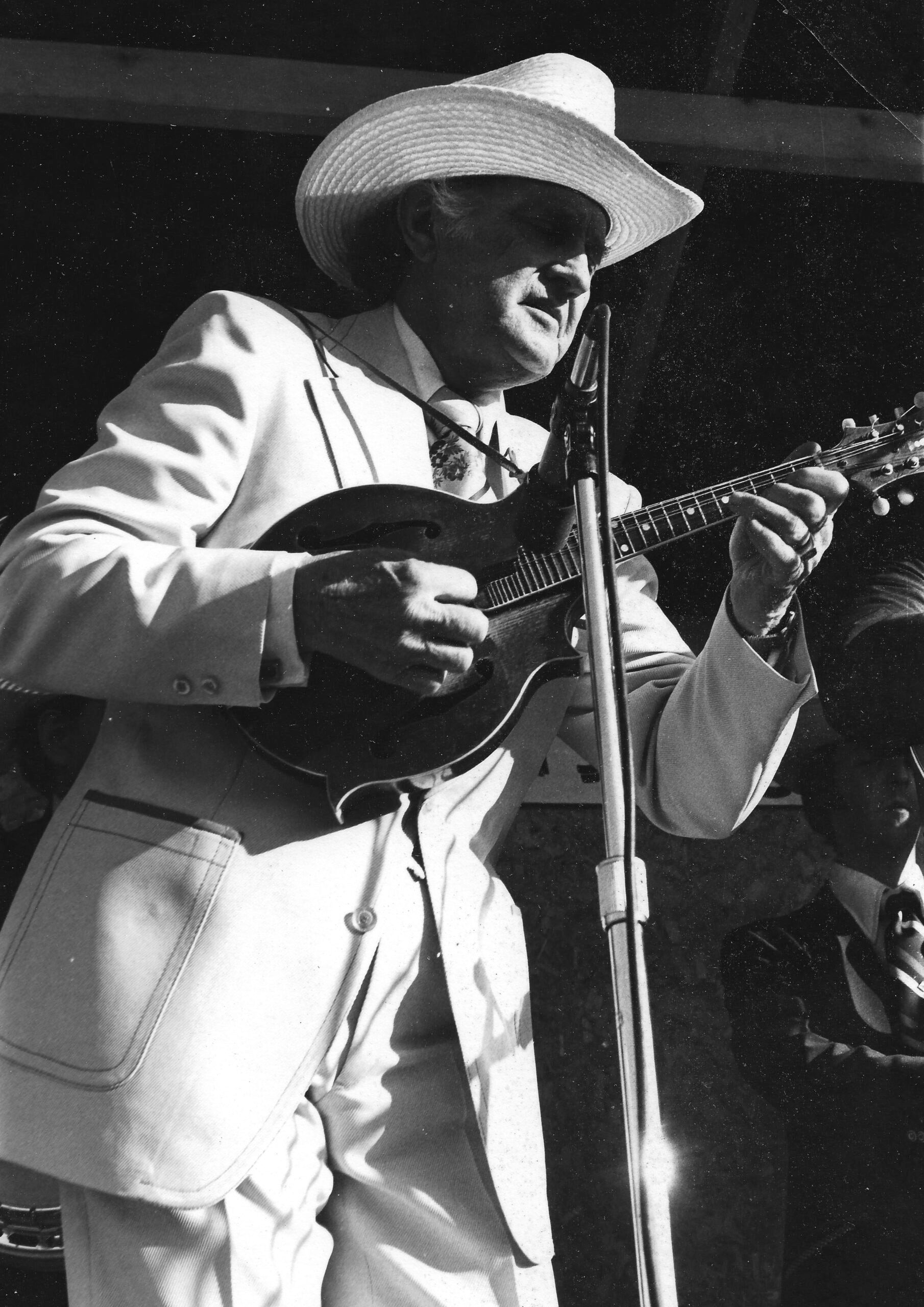

In the mid-1940s, Kentuckian Bill Monroe and The Blue Grass Boys developed all the elements that came to define bluegrass: acoustic instruments — mandolin, banjo, fiddle, guitar and bass — breakneck tempos, rich vocal harmonies and flashy solos known as breakdowns.

The man I met, an Oconomowoc resident by the name of Mark Hembree, played bass and sang with Bill Monroe’s band from 1979 to 1984. He even wrote a book about that time, “On the Bus with Bill Monroe: My Five-Year Ride with the Father of Blue Grass.” It was an experience that left a lasting impression, beginning with the audition.

“I caught them just before they went on stage for their last set,” Hembree said about his first encounter with the band. “’Well, what can you play?’ I said, ‘Well, how about ‘Road to Columbus?’ a Bill Monroe fiddle tune. (Fiddler Kenny) Baker just flew right into it. No count or anything. I grabbed the bass quick and jumped in. I made it in in time and played through that. And by the end of it, we were, you know, getting a good groove. So Butch Robbins, banjo player, came trotting by. He said, ‘We’re going to blast right out of here. But if you’ve got a business card or something, give it to the old man, you might have a job.’”

Hembree was hired as a member of The Blue Grass Boys soon after that audition.

For the bass-playing Wisconsinite, there was also the matter of adjusting to the South.

By some accounts, bluegrass requires that you sing higher than you should and faster than you can. Start, say, in the key of G, get ready to improvise, and you are off and running.

According to the book he wrote about his experiences, Hembree’s touring high road included playing at the White House and performing on Bill Monroe’s album “Master of Bluegrass.”

But the high road also put him “on a collision course with the rigors of touring, the mysteries of Southern culture and the complex personality of bandleader legend Bill Monroe.”

“Bill was not interested in whatever I had to say or think about much of anything, really,” said Hembree. “Finally, after a few weeks, I asked him, ‘Do you think I should bring my car and some stuff down from Wisconsin?’ And he didn’t say anything, he just barely nodded.”

After five years, Hembree broke away from The Blue Grass Boys and eventually formed his own bands.

Over the decades, the fortunes of bluegrass have risen and fallen with the trends of musical tastes, but it endures. A curious thing about bluegrass may account for its durability. Although the lyrics are usually about bankruptcy, breakups or other personal catastrophes, the music is so darn upbeat and cheerful that it sweeps those woes away.

You might not be able to ditch your troubles completely, but for a while, with bluegrass, you just might be able to outrun them.

“Wisconsin Life” is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS Wisconsin. The project celebrates what makes the state unique through the diverse stories of its people, places, history and culture.