A first-time author from central Wisconsin is working to ensure the Korean War is no longer remembered in silence, documenting the experiences of veterans who endured combat, captivity and decades of unspoken memories.

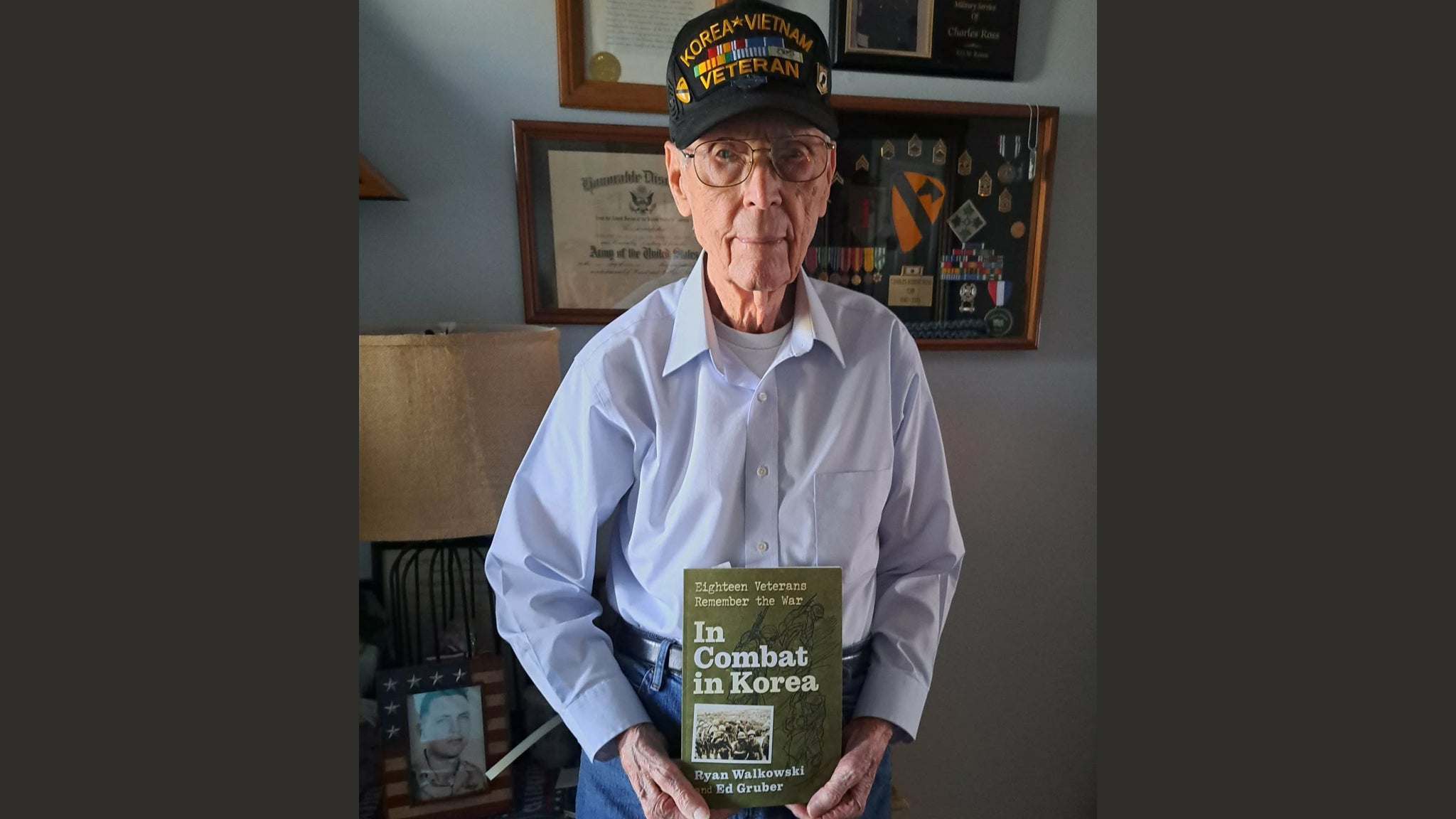

Ryan Walkowski, of Birnamwood, traveled across the country to interview veterans for his new book, “In Combat in Korea: Eighteen Veterans Remember the War.” The book, co-authored by Ed Gruber, centers on firsthand accounts from 18 men who fought in a conflict often overshadowed by World War II and Vietnam.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In a conversation on WPR’s “Morning Edition,” Walkowski said many of the veterans he interviewed had never spoken openly about their experiences.

“The average person just doesn’t understand what a combat veteran goes through,” he said.

Through the interviews, Walkowski said he gained a deeper understanding of the Korean War’s significance. He noted that U.S. and allied forces achieved the central objective of restoring the boundary between North and South Korea, even though the war officially ended with a ceasefire rather than a peace treaty.

Each veteran’s story underscores how deeply the war’s impact still resonates. For Walkowski, the goal is straightforward: to bring long-overlooked stories into the public record and ensure the Korean War is not forgotten again.

He is now working on a new book focused on Vietnam War veterans and is seeking participants willing to share their stories. Veterans interested in taking part can email Walkowski at ryan.author1993@gmail.com.

The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Shereen Siewert: This project began as a personal search for you. Tell us about that.

Ryan Walkowski: When I first started, I had no intention of writing a book. I just wanted to understand what my grandfather went through, because he never talked about it. I knew a local veteran in Wausau, and I went and interviewed him. His story is in the book.

Hearing this very profound, emotional stuff about combat, hand-to-hand combat, it was eye-opening. After that I found more veterans to talk with and took to Facebook to seek them out, and it spread like wildfire. That’s when I started traveling the country to document these stories. A lot of these Korean War veterans just repressed those memories for 70 plus years. I’d say 90 percent of the veterans I interviewed have never even told their wives or their families anything about it.

SS: How did you earn their trust?

RW: I didn’t really ask questions. I just asked them to tell me their story from the beginning. I will, of course, interject with questions, but I let them take it at their pace with what they felt comfortable sharing with me. Most of the time once they start to talk, it’s like the lid comes right off the top and all the details come out. But it varies. I’ve traveled the country to interview someone for just 15 minutes. Other times it’s a couple hours driving to meet another veteran who talks for hours. It was tough to whittle it down to just 18 veterans to feature in the book.

SS: One of the veterans in the book was held as a prisoner of war for nearly three years. How did hearing that story affect you?

RW: Well, when I interviewed Charles Ross in Cave City, Kentucky, all I knew was that he was an Army veteran and that he was willing to speak with me. It wasn’t until I was setting up my little camera stand when it came out. I mentioned that I had interviewed another veteran who was in the first Cavalry Division a day or two prior to meeting him. Charles asked me if he had been a prisoner of war, too, and I had no idea, but then he told his story. He told me exactly how it was, and it is a pretty emotional thing. There were tears rolling down his cheeks. I couldn’t imagine being held captive for almost three years. It’s emotional stuff. But a lot of these vets told me it’s something you have to witness to really understand.

SS: When you started this project, you were trying to understand what your grandfather went through. How did your understanding of war change as a result of this project?

RW: I never served, but I was always into the History Channel, the Band of Brothers series, but so much is about World War II or Vietnam. When I was a little kid, I hadn’t even heard of Korea. I gained a new perspective of what we really did on the Korean Peninsula. Learning about that is eye-opening. For one, we didn’t lose the Korean War. The soldiers who fought were part of something big. That’s pretty amazing. But hearing about the combat, it’s hard to fathom having to fight off hordes of people running at you at night with the added psychological effects of bugles and horns, whistles and screaming. The book gives a detailed view of what I’m talking about.

SS: What do you hope readers who have no personal connection to the military take away from this book when they read it?

RW: Just a better understanding of what our combat veterans go through. I mean, Korea is the forgotten war. It was dubbed that in the ’80s by some politician. We went there with the fundamental goal of establishing the 38th parallel, pushing the North Koreans out of South Korea, and we accomplished that.

If you have an idea about something in central Wisconsin you think we should talk about on “Morning Edition,” send it to us at central@wpr.org.