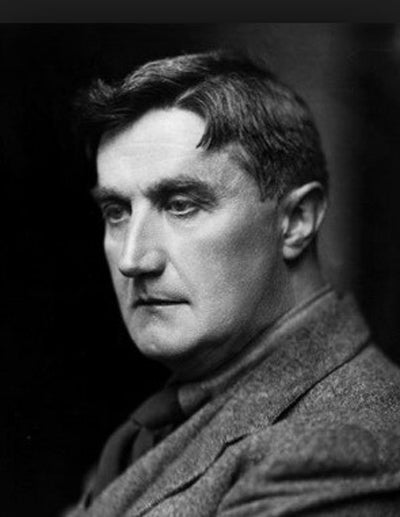

The composer was all caught up in conducting the debut of his first really big work. For several days, Ralph Vaughan Williams had been too nervous to sleep or eat right. He was unaware of friends and musical personages in the audience–Charles Villiers Stanford and the promising composer George Butterworth among them–all of them in Leeds for the performance of A Sea Symphony.

The timpanist offered helpful advice to calm Vaughan Williams’ nerves. “Give us a square four to the bar and we’ll do the rest.” The baritone, waiting with the composer before the performance and equally nervous, was less encouraging when he said, “If I stop, you’ll go on, won’t you?”

Vaughan Williams had lived with the symphony on paper for so long that in rehearsal he had been overwhelmed by his first hearing of it, remarking that the sound of the orchestra playing the first chords and the chorus entering with the words “Behold the sea itself,” had nearly blown him off the podium.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Once the symphony had been performed, Vaughan Williams was suddenly aware of being very hungry and very tired. Some of the singers probably felt the same way. The day after the debut a friend wrote an affectionate thank you note to Vaughan Williams in which she chided him for “expecting human larynxes to adapt themselves to impossible feats and to stretch or contract their vocal chords to notes not in their registers.”

Vaughan Williams came to the conclusion that the performance had not been particularly good, and yet musicians and audience alike had recognized the stature of the symphony. A performance at Oxford was arranged almost immediately, and Ralph Vaughan Williams would later find out that many members of the next generation would discover “contemporary” classical music through A Sea Symphony.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.