Scientists say communities around the Great Lakes should prepare for swings in high and low water levels to boost their resilience in the face of climate change.

A multi-agency panel of scientists discussed the uncertainty surrounding the effects of climate change on the Great Lakes Monday during the American Geophysical Union’s fall meeting in Chicago.

Water fluctuations on the Great Lakes are primarily driven by precipitation, evaporation and runoff from rivers and streams that drain into the Great Lakes Basin. Scientists say it’s uncertain how climate change will affect each of those factors, including Lauren Fry, a research physical scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Even so, Fry said NOAA’s Great Lakes Integrated Science and Assessments team expects warmer and wetter conditions on the lakes by mid-century. Wetter conditions are expected to vary by location and season on the lakes.

“The take home message is that resilience and adaptive management really needs to consider both high and low water levels going forward,” Fry said.

Until recently, the lakes experienced a period of consistently low water levels from 1998 to 2013 with Lake Michigan hitting a record low in 2013. In the years since, levels climbed rapidly and reached record highs between 2017 and 2020 before dropping steadily due to dry, mild weather.

During low levels, precipitation varied but remained relatively low while evaporation was high, according to Alexander VanDeWeghe, a research assistant with the University of Michigan’s School for Environment and Sustainability. VanDeWeghe said that led to a loss of water from the Great Lakes, which is in sharp contrast to patterns seen from 2014 to 2020. As levels reached record highs, the lakes saw very high precipitation and below average evaporation.

Drivers of those changes in lake levels have helped with modeling future conditions on the Great Lakes, and research indicates climate change will drive water levels higher.

“We see that, although there’s some variability across the lakes and across the months of the year, the long-term average water level in this study — it’s projected to have slight to moderate increases something on the order of a couple inches up to just under a foot,” VanDeWeghe said.

Those findings are consistent with a study from Michigan Technological University. That study found Lake Superior is expected to rise on average by 7.5 inches while levels on the Lake Michigan-Huron system is projected to increase 17 inches by 2050 due to climate change.

Even so, VanDeWeghe noted their results are highly variable with a wide range of outcomes from a decline of several inches in water levels to an increase of 20 inches over that time.

In recent years, surging water levels and extreme storms on the Great Lakes have battered infrastructure along coastal communities and eroded shorelines. In Wisconsin, lakeshore communities estimated they will spend almost $250 million to repair damage linked to climate change.

Those communities may see more flooding in the future as scientists project climate change will drive more intense storms and higher water levels, according to researchers with the University of Michigan.

Researchers used a flood forecasting model to simulate hazards that people have seen along Lake Michigan over the last three years to determine which groups may be most vulnerable to flooding, according to Yi Hong, a postdoctoral research fellow with the university’s NOAA-funded Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research. Researchers examined populations based on race, age, education and income.

Hong said they found the Green Bay and Chicago areas are most susceptible to flooding with up to 30 percent of certain census tracts flooded in the last several years.

“We can see that the socially vulnerable people are more likely to live in flood prone areas, especially for minority and also for low-income populations,” Hong said.

And the Great Lakes have become home to large populations along its shores with around 27 million people residing in its coastal counties. In Illinois, the coast makes up less than 1 percent of the Great Lakes shoreline. But two coastal counties are home to almost one-third of the U.S. population bordering the Great Lakes, according to Riley Balikian, assistant research scientist with the Illinois State Geological Survey.

Balikian said the dynamic shift in water levels and its effects on erosion highlights the social, economic and environmental concerns facing coastal communities. In the last decade, Lake Michigan rose more than 6 feet in less than eight years before falling about 3 feet in the last three years.

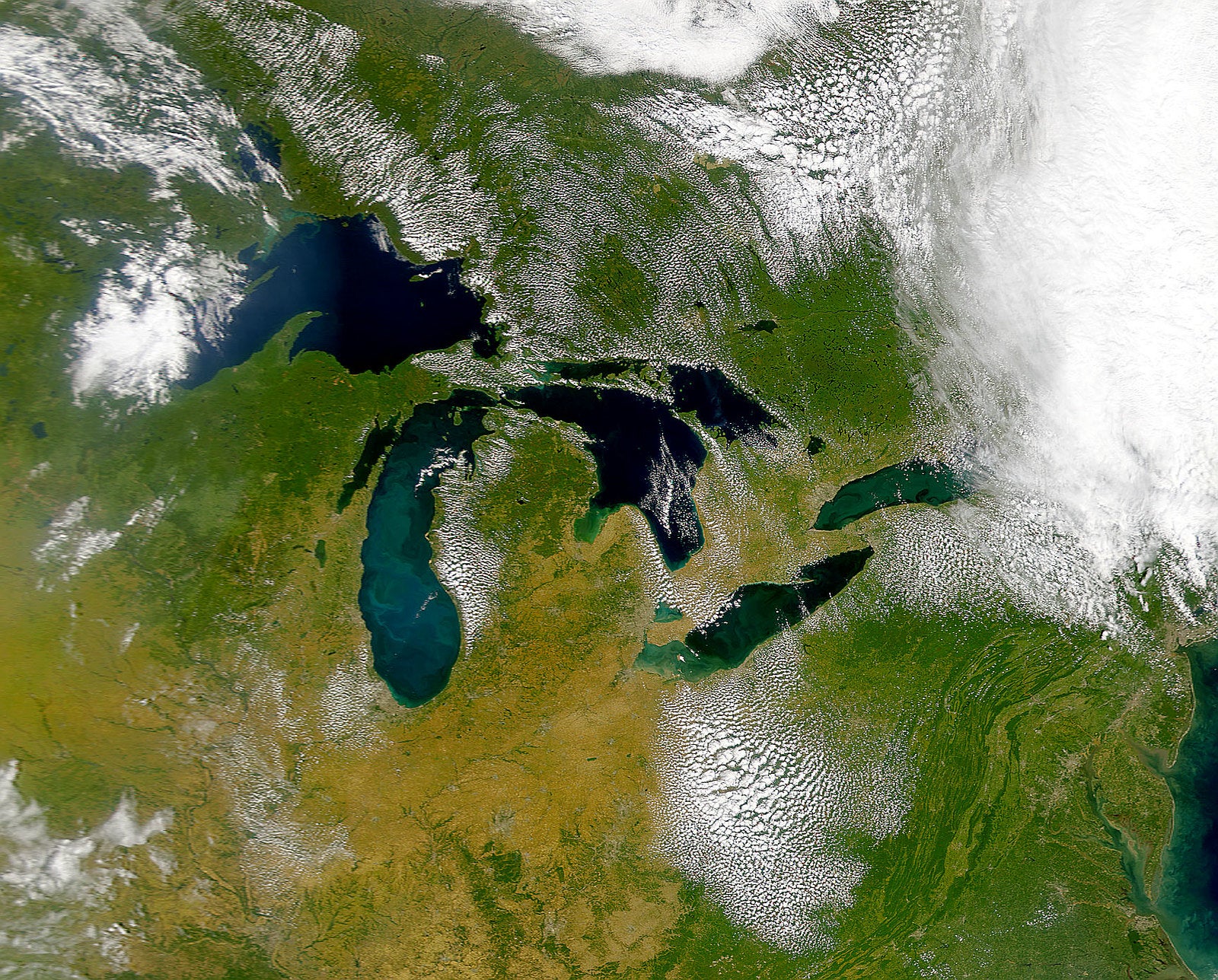

Now, Balikian and other scientists are using satellite data to document the effects of erosion on Great Lakes coastal shorelines. Satellite images of a single site 50 miles south of Chicago show parts of the shoreline have lost up to 100 feet in just the last six years.

“This is an example of how you can get some large changes in some small periods of time when there’s a dynamic lake level and other processes happening,” Balikian said.

He said he hopes satellite data can be used to better understand the causes and consequences of erosion along the Great Lakes shoreline amid a changing climate.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.