There are many contradictory myths about Northwoods lumberjacks and the work they did in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

They were depicted as hard-living, violent men, but also as upstanding, conservation-minded gentlemen.

Recently, Willa Hammitt Brown, the author of the book “Gentlemen of the Woods: Manhood, Myth and the American Lumberjack,” visited WPR’s “The Larry Meiller Show” to help sort out logger legend from lumberjack reality.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The myth of Paul Bunyan

It is fitting that a culture that has been mythologized as much as the logging industry is widely represented by a mythical figure: the fictional Paul Bunyan.

Contrary to Bunyan’s current folk hero status, Hammitt Brown recalled that in the earliest tale written about him — 1906’s “Round River Drive” — Bunyan was “a jerk.” The story depicted Bunyan as a dishonest logger who tricked his men into taking logs around and around the same river so that he would never have to pay them.

For today’s more heroic vision of Bunyan, Hammitt Brown credited an advertising copywriter named William Laughead. She said of promotional materials dating back to 1916 for the Red River Lumber Company: “Laughead collected a bunch of tall tales about Bunyan, sanitized them and made this cheerful, sweet, good-hearted guy out in the woods having a good time.”

Laughead is also credited with naming Bunyan’s blue ox “Babe” and increasing Bunyan’s heights to impossible proportions.

“That’s the image that took over,” Hammitt Brown said. “We erased a lot of the real history of what those men had been like. Now we had this very easy, friendly symbol that we have all become very familiar with.”

The harsh reality of the logging industry and lumber towns

What the Bunyan myth helped to cover up is what Hammitt Brown called the “exploitative nature of the logging industry” that she likened to western mining or oil rigging that produced “incredible environmental damage.”

Instead of a destroyer of the woods — particularly the Northwoods of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan, where the Bunyan myth continues to loom the largest — Hammitt Brown said Bunyan was portrayed almost as a conservationist who was “working with the woods, like sailors in the sea or farmers and the land.”

Also contradictory to the clean-cut image of Bunyan, she said lumber towns — communities that arose around lumber mills or logging operations — were as violent, if not more violent, than the cattle towns of the Old West.

“Those lumber towns were just full of brothels and taverns and largely the police let what happened happen as long as it didn’t come into the rest of the town,” she said.

The term “skid row,” which is now associated with an unseemly part of a town, originally referred to the area where logs were “skidded” or transported to a lake for further transport.

Hammitt Brown talked about how her visit to the former lumber town of Seney in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan encapsulated the character of these communities. At the town’s historical museum, she recalled that there was a photo of the Women’s Woodwind Society that she said showed a “respectable middle class, all of these ladies sitting in their proper little band.”

And then in the same museum were pictures of the town’s brothels with women beckoning to customers from the top floors of hotels.

“And some of the women are the same women. The town was too small to put together a woodwind band without a few prostitutes in it,” Hammitt Brown laughed.

Back in Wisconsin, “Hurley and Hayward were some of the roughest towns, just filled with lumberjacks and filled with taverns and brothels,” Hammitt Brown said. “But now they reclaim that history as a real point of pride. Hayward is where the Lumberjack World Championships are. But at the time, they were not exactly respectable. And the year-round citizens were doing anything they could to try to keep the lumberjacks either out of town or at least contained where the rest of the town could be safe, and the lumberjacks could just fight each other and not get into the main part of town.”

Lumberjacks were seen as not OK

Hammitt Brown said lumberjacks, like other itinerant workers of the era, were feared and distrusted because of their lack of family ties or meaningful attachment to the community.

“Men were thought to have natural urges,” Hammitt Brown said. “And without the restraint imposed by a family, it was feared they might be capable of doing anything.”

Hammitt Brown believes these are ideas that have not gone away.

“I think you can look at the way we talk about migrant workers today and you can see a lot of parallels in this scapegoating and fear that these people aren’t committed enough to the community and might therefore be a danger,” she said.

No ‘glamping’ here

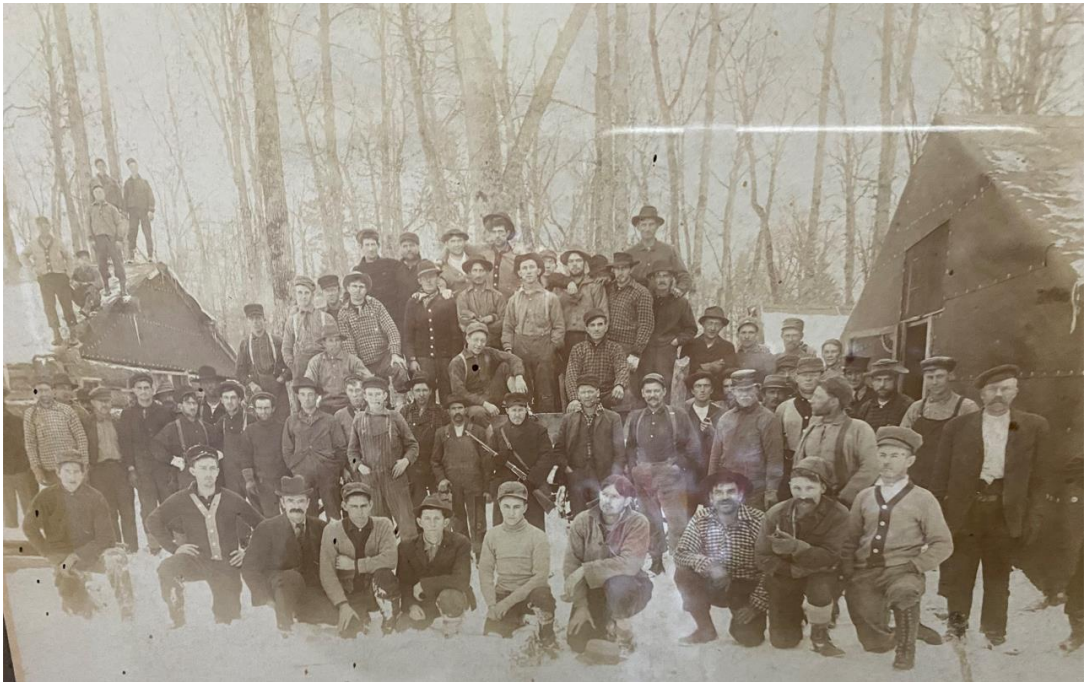

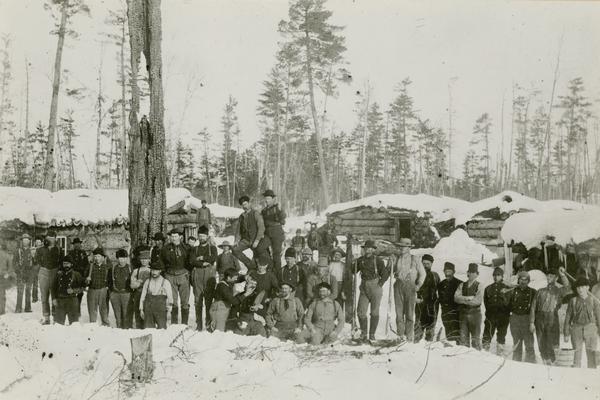

Hammitt Brown did not romanticize the conditions at the logging camps, calling them “deeply unpleasant.” She explained that a typical camp consisted of a main shanty where between 50 and 120 men would sleep in very close quarters.

“Some men were known to put on their long underwear at the beginning of winter and take them off at the end and never in between,” Hammitt Brown laughed. “And at the end of the day they would hang their wet socks over a big iron stove. So, you just have to imagine 100 pairs of wet socks steaming into a poorly ventilated space with 100 unwashed men bedding down for the night.”

Lumberjacks were typically paid between $3.50 and $4 a week, but some camps would hold back payment if loggers didn’t cut enough wood to fulfill their contract. In that case, they would just have been working for food. Hammitt Brown cited this as the origin of the phrase “working for beans.”

The environmental consequences of logging

“The scale of lumbering is really hard to imagine,” Hammitt Brown said.

Central Wisconsin was one of the most devastated areas of the Northwoods region, and in the late 1920s and early 1930s there was even a dust bowl there, second only in size and severity to the more famous one that occurred in the Great Plains.

“During the 1930s, even though only about 10 percent of the population of Wisconsin lived in the area, over 75 percent of government aid was going to that area,” she said. “That’s because it had been so ecologically devastated by this industry.”

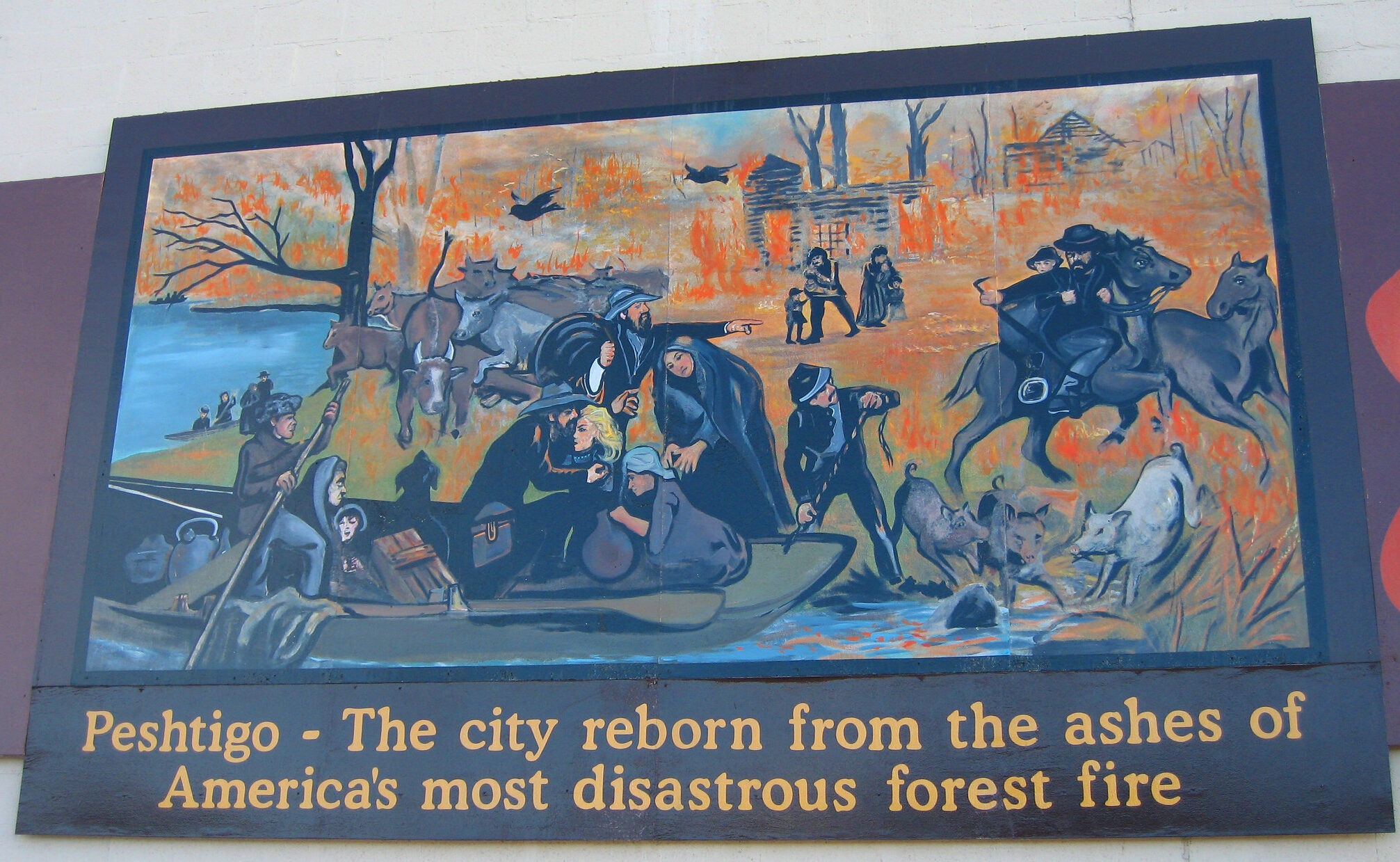

Hammitt Brown also explored the connection between the logging industry and historic wildfires, citing that four out of the 10 deadliest fires in American history — the Peshtigo fire in Wisconsin, the Great Chicago Fire, the Thumb Fire in Michigan, and the Cloquet fire in Minnesota — could be connected to the logging industry.

“As the industry went, they would clear cut and anything that wasn’t worth saving, they would just leave,” Hammitt Brown said. “You had these miles and miles of forest debris and those would catch fire incredibly quickly. These fires covered an area almost the size of Delaware.”

The racial disparities of lumber towns

Lumber barons of the era either bought small tracts of land or simply stole it from the Anishinaabe and the Menominee people with the assumption they could get away with it.

“They were successful in doing so,” Hammitt Brown said.

She said the Anishinaabe people were the most negatively affected by the logging industry, lumber barons and related federal laws such as the Dawes Act, which authorized the president to survey tribal lands and divide it into allotments for individual Native Americans. Many Anishinaabe people sold their plots to lumber barons since the land wasn’t large enough to provide a sustainable living.

Beyond the economic and land loss, Hammitt Brown said the Anishinaabe suffered by being at the bottom of the racial hierarchy within the camps. It was thought that white men were the best workers because they had to learn logging skills while it was assumed that those same skills came natural to the Anishinaabe people.

“They supposedly had the natural ability of someone considered to be closer to nature. So any skill was sort of discounted,” Hammitt Brown said.

The staying power of the lumberjack myth

The conclusion to Hammitt Brown’s book is subtitled, “The Stories We Still Buy.” By citing modern-day promotional campaigns, the popularity of urban ax-throwing bars and her personal travels and research, she said the lumberjack myth not only continues, but could be stronger today than ever. It’s a myth that perhaps even Paul Bunyan himself would struggle to cut down with his mightiest ax.