Joe Martin Rose was the first person to welcome Patty Loew to the Bad River community when she reconnected with the tribe 45 years ago. Loew is a Bad River tribal member, but she grew up in Milwaukee. It wasn’t until she began teaching and doing outreach work in her 20s that she started going to the reservation.

“He became like a second dad to me,” said Loew. “Everything I learned about the Ojibwe, I learned from Joe.”

Better known to some by his Ojibwe name Moka’ang Giizis, or Rising Sun, Joe Rose died on Feb. 23 at the age of 85 from complications of contracting COVID-19.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Born in Oklahoma, the son of Carl Rose Sr. and Mary “Dolly” Rose, Joe grew up on the reservation in northern Wisconsin during a time of kerosene lamps, outhouses and wood heat. He learned about plants and medicines from his grandfather Dan Jackson, gaining an appreciation for the natural world. Loew, who is a journalism professor at Northwestern University, said that’s something he passed on to all who knew him.

“He was one of the most amazing individuals I’ve ever met,” said Loew, pausing as she blinked back tears. “Good communities have a center and Joe Rose was the center of Mashkiiziibii — Bad River.“

More than 6,500 Wisconsinites have died from COVID-19 in the last year, but the heaviest toll has fallen on Native Americans who are dying at the highest rate from the virus. More than 6,300 cases of the virus have been confirmed among American Indians statewide, claiming at least 90 lives since April of last year.

Bad River Tribal Chairman Mike Wiggins looked up to Joe as a kid growing up on the reservation. To him and others, Joe was an encyclopedia of knowledge about the history of the Anishinaabe people and their cultural practices. He taught people to live in a way that would benefit those for seven generations to come. Wiggins said that included the seven grandfather teachings that urge one to live with humility, love and respect for all creation.

“Joe was a compass point that always helped us remember our bearing,” said Wiggins. “And so, from a community perspective, all of our elders are real sacred because they give us those tangible ties to the past and help us remember where we came from. And they help us get perspective in real time, so that we can make good decisions about where we’re headed.”

Wiggins said the tribal elder, who was a member of the Midewiwin or Grand Medicine Society, often spoke of the seventh fire prophecy that foretold of a time when people would be left with a choice between two paths.

“One path would lead to the continuing degradation and ultimate demise of Mother Earth, and the other path would lead us back to harmony,” said Wiggins.

Wiggins said Joe believed in that prophecy and made it his mission to protect and preserve natural resources. He passed on those teachings to the youth at Bad River and through a Native American studies program that he directed at Northland College in Ashland. That’s where Lac Courte Oreilles tribal member Mic Isham first met Joe as a student in 1983.

“That guy saved my life, and I’ll never forget it ‘cause I swear I don’t know where I’d be without him,” said Isham.

Isham, whose dad is Native and mom is white, remembers struggling with his identity. Now executive administrator of the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), he said Joe taught him the Anishinaabe culture and helped him find his way during a tumultuous period. Around the same time, Isham recalled protesters were gathering at boat landings to hurl rocks and insults at tribal spear fishers after a federal judge reaffirmed their treaty rights to hunt, fish and gather in ceded territory.

“I couldn’t figure out how they were not throwing punches and things like that, and Joe explained to me — basically with a European proverb — you catch more flies with what is it? Honey than vinegar or something like that?” said Isham. “And when they go low, you go high.”

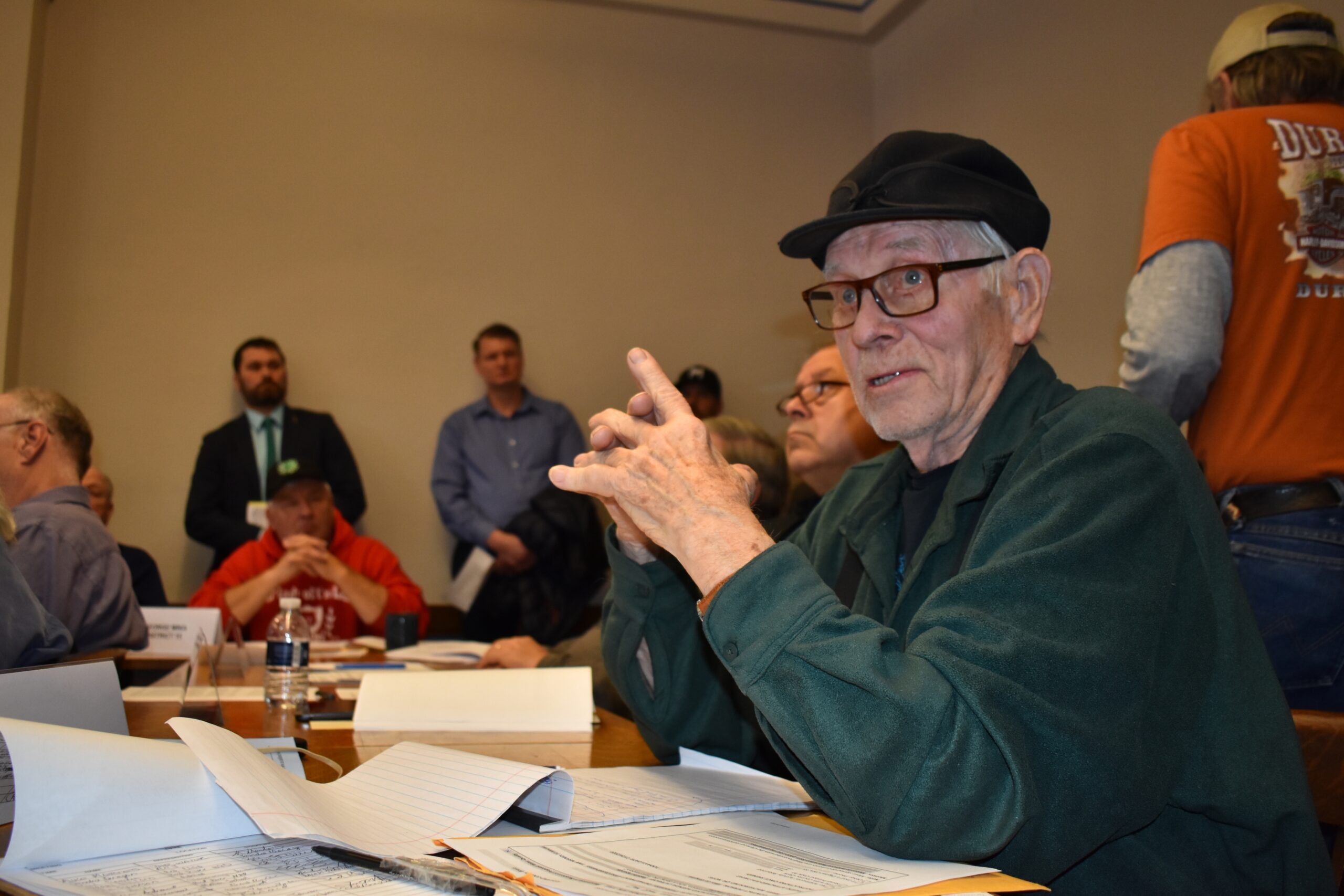

Joe would defend tribal treaty rights and the natural resources on which they relied throughout his life. During a contentious debate over iron mining, he and other tribal members traveled to the state Capitol in 2012 to protest a Republican bill that weakened environmental standards and sought to pave the way for a $1.5 billion iron ore mine proposed upstream from the Bad River reservation. The mining company eventually abandoned the project in 2015.

“We can’t put any price on the wild rice or any of those other resources that our hunter-gatherer society would use,” said Rose at the time.

Former state Sen. Bob Jauch, D-Poplar, said he first got to know Joe during the mining debate. The tribal elder invited Jauch and his Republican colleagues to his round house on the reservation.

He likened meeting Joe to that of spending time with the Dalai Lama. An amazing storyteller, Jauch recalled him recounting the history and mistreatment of Native Americans with a rhythm and tranquility in his voice like the wind.

“We learned not only about the history and the perspective that he and other tribal members had about mining in general, but particularly the Penokees and the importance of the Bad River Watershed to Lake Superior in our lives,” said Jauch. “He really left us living in their shoes to understand their perspective.”

Danielle Kaeding/WPR

Philomena Kebec worked with Joe during the mining debate as an attorney with GLIFWC and later served with him on the Ashland County Board.

“He was always there with his strong voice, supporting other people, and really advocating for the voices of community people to be heard,” said Kebec.

Losing Joe to COVID-19 amplified for Kebec the difficulty of controlling the spread of a virus that often left people divided over how to keep it in check. Tribal communities have suffered some of the highest rates of cases and deaths — often losing elders like Joe.

“It just seems like another expression of indifference toward tribal people,” said Kebec.

When he first contracted the virus, those who knew him were confident Joe was recovering before he took a turn for the worse. Even at his age, Loew said he was strong, healthy and active. She said that made his loss even more puzzling and heartbreaking.

“When you have a small homogenous community, where the language is endangered, and so much of culture is embedded in language, to lose those elders who can speak the language and know all the truths embedded in that land — is so devastating,” said Loew.

[[{“fid”:”1463461″,”view_mode”:”embed_portrait”,”fields”:{“format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EBad%20River%20tribal%20member%20Dylan%20Jennings%20and%20tribal%20elder%20Joe%20Rose%20show%20off%20their%20catch%20on%20the%20Lake%20Superior%20shoreline.%3Cbr%20%2F%3E%0A%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20Mike%20Wiggins%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Dylan Jennings With Joe Rose”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Dylan Jennings With Joe Rose”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EBad%20River%20tribal%20member%20Dylan%20Jennings%20and%20tribal%20elder%20Joe%20Rose%20show%20off%20their%20catch%20on%20the%20Lake%20Superior%20shoreline.%3Cbr%20%2F%3E%0A%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20Mike%20Wiggins%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Dylan Jennings With Joe Rose”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Dylan Jennings With Joe Rose”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Dylan Jennings With Joe Rose”,”title”:”Dylan Jennings With Joe Rose”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]

Before he died, Dylan Jennings spoke with Joe. The Bad River tribal member recalled him saying that it was going to be a long road to recovery, and he would need continued prayers and positive energy to “make it out of this one.” He asked Jennings to consider taking his place on the county board.

On March 9, the board appointed Jennings to Joe’s seat and passed a resolution honoring the tribal elder and his years of service. Jennings said many are still in shock over his loss, but he knows Joe would be proud to see community members continuing his legacy.

“He’s made a huge, huge enough impact to where his memory lives on through our language being revitalized and our cultural way of life and our ceremonies being revitalized and still being carried forward,” said Jennings.

Like Jennings, those who knew him aim to ensure those teachings will live on for the next seven generations.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.