It looks like Wisconsin will be counting on more animal waste digesters to handle the growing amount of cow manure at large dairy farms. The state’s Public Service Commission recently authorized spending up to $20 million in utility ratepayer money on the large waste-to-energy units.

But the record on digesters is mixed, and they don’t completely get rid of nutrients that can pollute local drinking water and surface water.

One digester that’s been operating for years is at the family-owned Vir-Clar Farm near Campbellsport. Vir-Clar’s 1,800 cows are milked three times a day, with each cow producing about 11 gallons daily. But cows, being big eaters, also generate about 80 pounds of manure each day.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

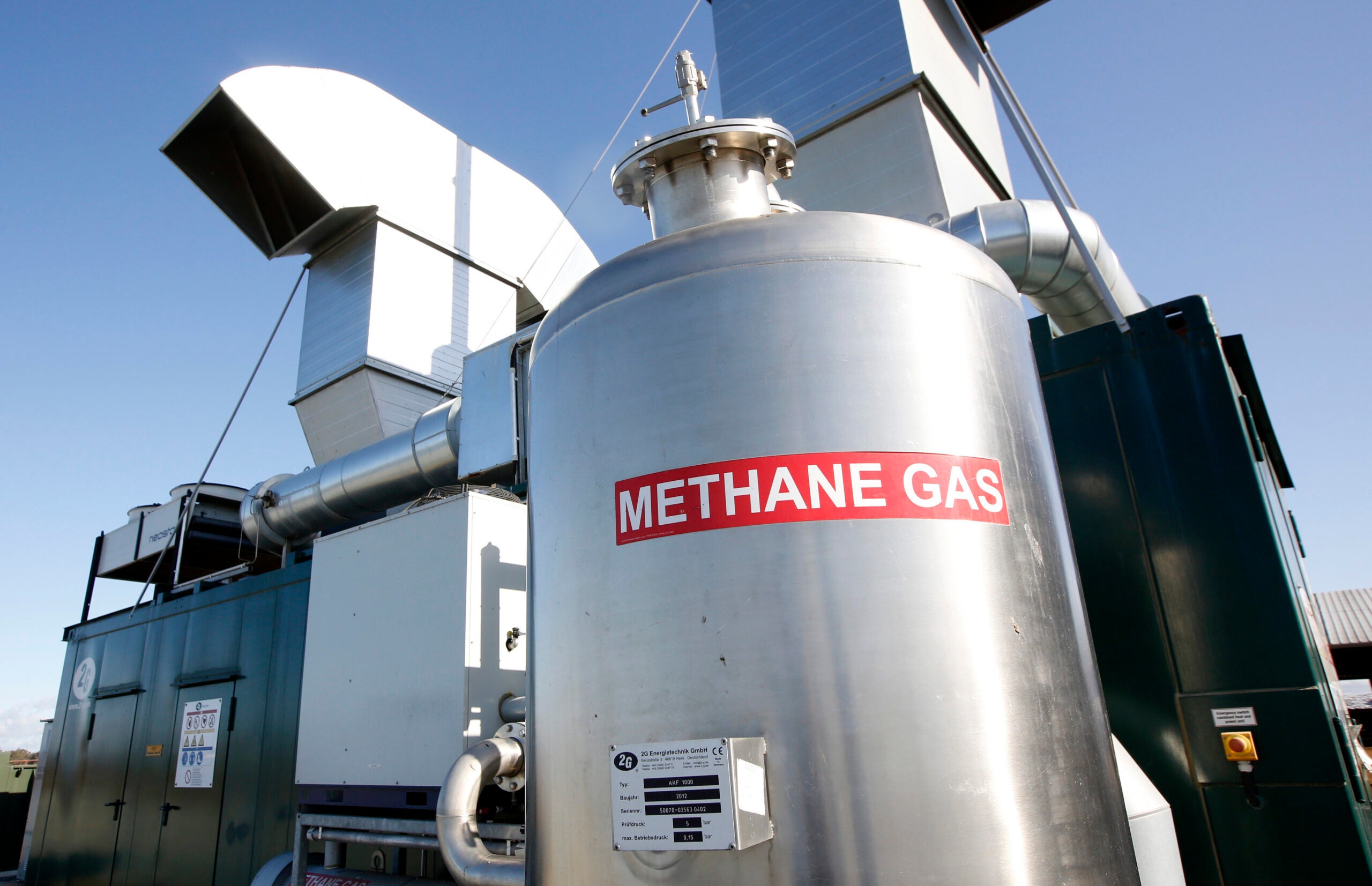

Grant Grinstad, a manager at Vir-Clar, recently told a group of reporters from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources that the waste is collected and pumped to large covered tanks called digesters. Methane gas from the decaying material is captured and sent to Vir-Clar’s generation room, where two engines burn the gas. That cranks out electricity for the power grid — enough to light the homes of roughly 800 customers of the local utility, Alliant Energy.

Grinstad said Vir-Clar had to invest a few million dollars in all the equipment but the economics work at his farm.

“Fortunately, we’re pretty close to Fond du Lac, so the ability to connect to the grid via Alliant, we were fortunate from our location,” he said, but added that cost may limit other farms from adding manure digesters. “When you look to rural America of where we can site digesters on larger dairy, typically they’re further away from the technology, the super power grids in order to feed back in. So that’s where the costs come into play.”

The manure pond at Vir-Clar Farm. Chuck Quirmbach/WPR

About three dozen Wisconsin farms have manure digesters, some built partly with ratepayer assistance through the state Focus On Energy program. And some conservation groups would like more dairy operators to get in the game.

Joseph Britt of the Sand County Foundation said a digester winds up reducing harmful fertilizer runoff into lakes and streams since farmers are under less pressure to spray the waste on fields, where it may run off into local waters.

“We’re interested in expanding the number of tools available to farmers to keep nutrients on the land or at least out of the water,” Britt said.

But there’s also a question for some about the reliability of digesters, most notably at a three-farm facility built a few years ago near Waunakee.

The current owner is Clean Fuel Partners, but a couple years ago, under a different name and a different owner, the Dane County-backed digester facility had several leaks of manure and the nylon top blew off one of the three digester tanks because of a small explosion.

With new ownership, Clean Fuel CEO John Haeckel said the public should no longer be concerned about the taxpayer-funded facility.

“We’re in the business of pipes and pumps and poop. Things break,” Haeckel said. “We don’t want them to break. We believe we’ve got the backups and we’ve got the spares necessary to quickly remediate any problems we might have.”

Haeckel also says questions that surfaced under the previous owner as to whether the digester met targets for removing phosphorus from the unburned waste have been answered. He said about two-thirds of the nutrient is now taken out before the remaining liquid waste is spread on fields as fertilizer.

But if the state moves ahead with boosting money for digesters, phosphorus removal will get more scrutiny from environmentalists. Keith Reopelle of Clean Wisconsin said he hopes the latest technology is used, even if it’s more costly.

“Many of them are chemical processes, which really chemically separate the phosphorus from the rest of the liquid output of the manure,” Reopelle said. “You need that phosphorus removal piece to really see a significant benefit to water quality.”

Reopelle also said he agrees with some Kewaunee County residents who are skeptical of the state’s plan for a new digester there.

Reopelle said putting in a new waste-to-energy unit shouldn’t be a substitute for a more comprehensive plan to address manure spreading in the area.

The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture Trade and Consumer Protection says the state’s request for proposals for new cow waste digesters will be issued in early January.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.