Schools throughout Wisconsin got their state test results back this week. The latest scores show students in both public and private schools are doing about the same on standardized tests as in previous years. The state’s achievement gap, which is regularly one of the highest in the nation, remained largely untouched.

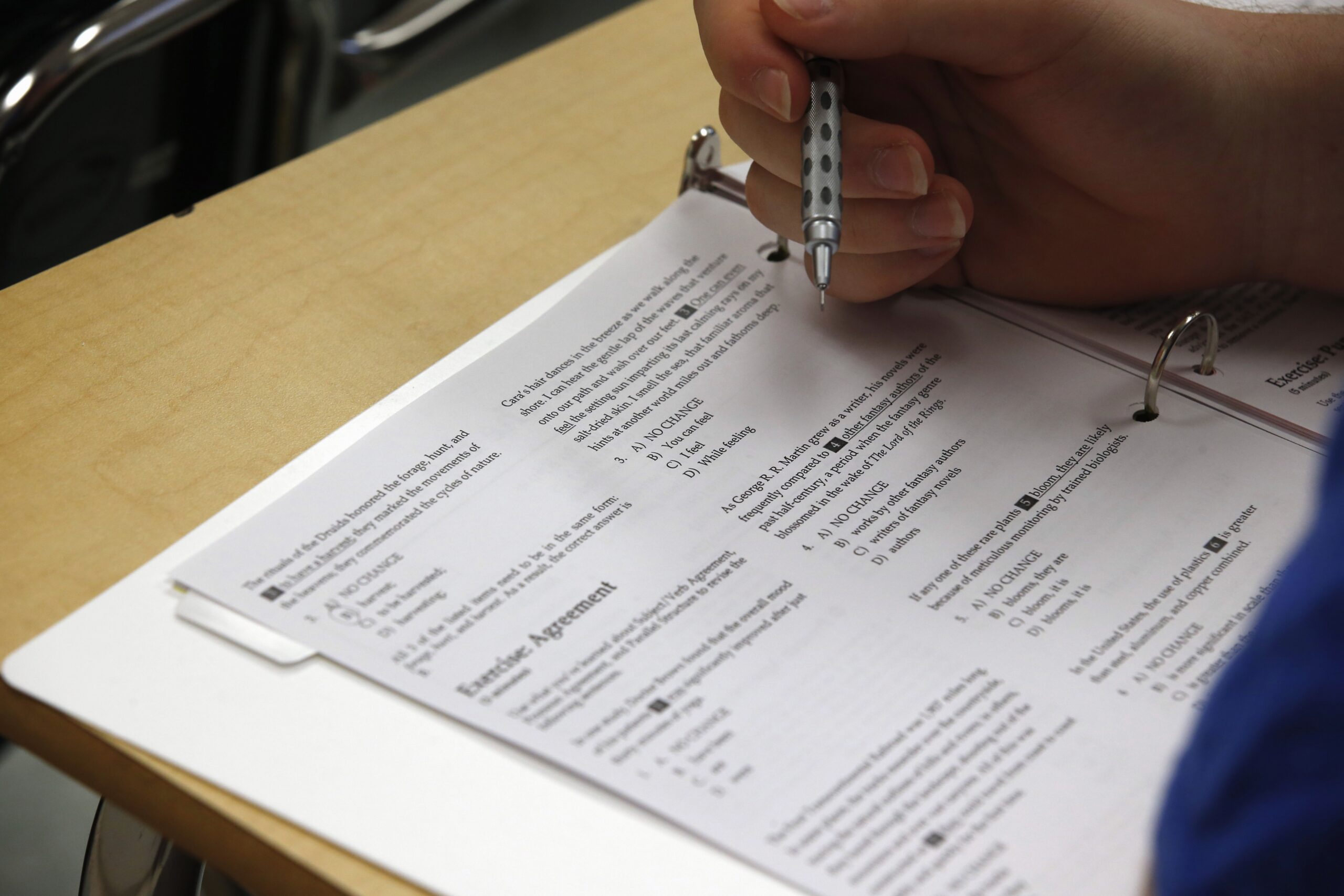

Students in grades three through 11 take the Wisconsin Student Assessment System tests in the spring, which range from the Wisconsin Forward Exam — an assessment of math, science, social studies and English language skills — to the ACT, a national college admissions test.

About 40 percent of Wisconsin students scored proficient or advanced in English language arts, math, and science in the 2017-18 school year. That’s similar to the past few years.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Tom McCarthy, a spokesman for the state Department of Public Instruction which administers the Wisconsin Student Assessment System and provides the data, did identify some movement.

“The most notable change is math performance,” he said. “We have a steady, over three-year increase in math performance, and it’s something that seems to be across systems and it seems to be across subgroups.”

But the increase is modest. In the most recent year, 41.1 percent of students scored at proficient or advanced in math, up from 40.3 percent in 2015. McCarthy said DPI intends to dig into these scores and follow upcoming years to identify what schools are doing right.

The positive gains in math did not distract from the more persistent problem reflected in the data. Wisconsin’s chasm of an achievement gap did not narrow.

“With consistent results we are still seeing consistent achievement gaps,” McCarthy said.

Just 12.7 percent of black fourth-graders scored proficient or advanced in English language arts, compared to over half of their white peers.

In certain areas, differences appeared to decrease. “But it is not the type of gap closure we would like to see,” said McCarthy. Rather than the lowest scorers doing better, the highest performers did slightly worse than before.

“When we talk about closing gaps what we’re hoping is that the upper level students continue to perform well and we’re able to bring our subgroups up in performance,” McCarthy added.

University of Wisconsin-Madison sociologist Eric Grodsky traces the problem, and the solutions, of the achievement gap back to kindergarten.

“If you really want to resolve disparities, try to prevent them from happening in the first place,” he said. “Getting kids to school on a more even footing would go a long way.”

Grodsky says how much a parent earns affects how well a child does in school, and that systemic poverty is a significant part of performance gaps.

Full results are available here.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.