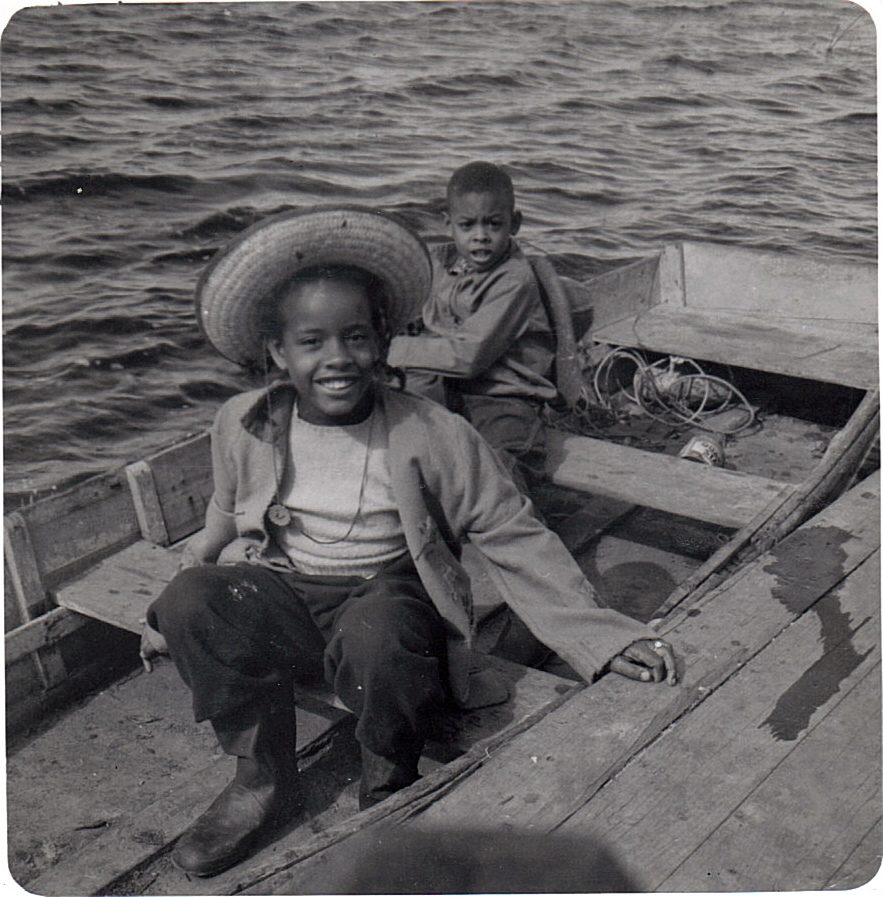

Peter Baker will never forget his first visit to Lake Ivanhoe. It was 1966. He was 9 years old and his friend brought him up from Chicago on a fishing trip. They caught dozens of fish, mostly bluegills and crappies.

“We went home and I ran in the house with all these fish and I showed my mother, ‘We were up there at Lake Ivanhoe, and it was all Black!’” said Baker, now 66. “And the first thing she said is, to my father, ‘Ernest, we’re going up there next week.’”

The tiny subdivision of Lake Ivanhoe is nestled beside a quiet lake, just 6 miles east of Lake Geneva. The Bakers bought a house on Tuskegee Drive and moved the family up from Chicago. Peter spent his days fishing, swimming and running through the woods. During the era of sundown towns, where African Americans were not welcome after dark, Baker said Lake Ivanhoe was a refuge.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“This was about as safe as life could get up here, because we literally could sit in the middle of the roads at night time and watch the stars and talk and play,” Baker said. “The freedom was unbelievable.”

It wasn’t until decades later that Baker learned that feeling was the whole idea when the community was dreamed up a century ago as a Black-founded resort community. Now, a small group of local residents is working to ensure that history is recognized after nearly being lost.

Over the past several years, the nation has grappled with whose history is preserved in our statues and monuments. Of Wisconsin’s 600 historical markers, just seven commemorate the history of the state’s Black residents. And none recognize the history of Hmong, Latino or LGBTQ communities.

The Wisconsin Historical Society is trying to change that, said Fitzie Heimdahl, who coordinates the state’s historical marker program.

With grant funding from The William G. Pomeroy Foundation, they’re partnering with organizations from Black and other marginalized communities to add nearly 40 new markers over the next three years.

“A large part of the reenvisioning process of the marker program is to make sure that diverse stories are being told, and that the histories of our state’s peoples and cultures are being told by these groups themselves,” Heimdahl said.

Lake Ivanhoe will be one of their first new markers.

The dream of Lake Ivanhoe

Lake Ivanhoe was the vision of three prominent Black men from Chicago — Jeremiah Brumfield, Frank Anglin and Bradford Watson.

The trio recognized growing racial tension as a result of the Great Migration that brought millions of African Americans north. As communities merged, Black families faced restrictive covenants and redlining that barred Black families from certain neighborhoods, and even violence from white people intent on keeping them out.

In 1919, riots broke out in Chicago when a Black boy was killed by a white man at a beach and the police wouldn’t make an arrest.

Amid this racial unrest, Brumfield, Anglin and Watson wanted a safe place to take their families on vacation. White realtors had popularized Idlewild, Michigan as a resort for Black families, but it was too far a drive from Chicago. So they decided to build their own.

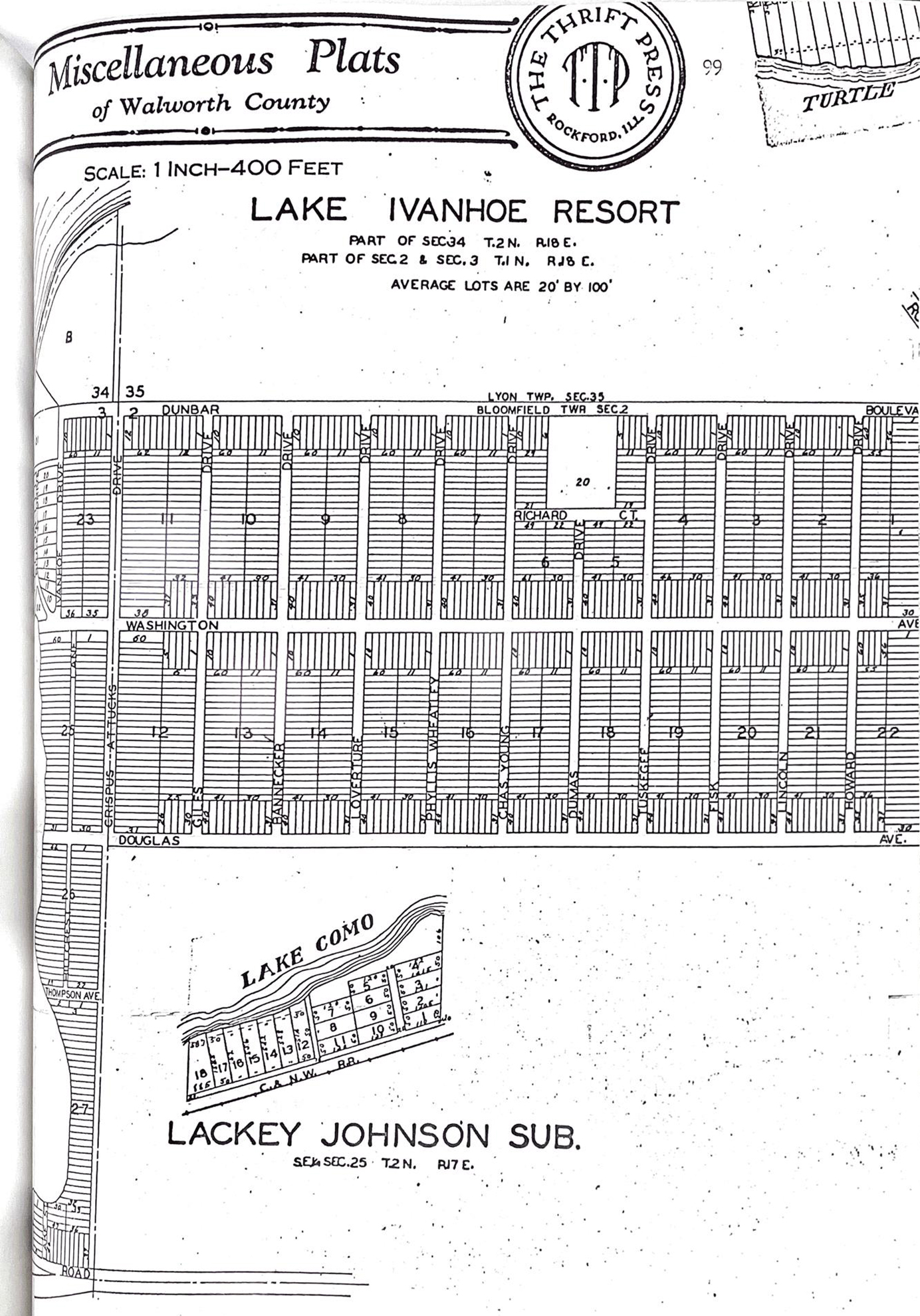

The three men drew up plans and sought financial backing from both white and Black investors. In 1926, they purchased an 83-acre farm on Ryan Lake in Walworth County. A white real estate agent named Ivan Bell agreed to broker the deal, and the lake was later renamed in his honor.

They carved out lots, named the streets after famous Black figures — Dunbar Boulevard, Phyllis Wheatley Drive, Douglass Avenue — and placed ads in Chicago newspapers.

On a hill overlooking the lake, they built a large pavilion where jazz great Cab Calloway performed on their opening night in 1927.

The resort was an immediate hit. Black families arrived in droves to purchase lots and enjoy the outdoors. There were fishing contests, concerts, prize fights and beauty pageants.

But sales plummeted when the stock market crashed in 1929. The pavilion was dismantled, and the unsold lots went into foreclosure.

In 1934, Edward Sternaman, a white football player for the Chicago Bears, purchased the unsold property at Lake Ivanhoe. Intending to turn the area into a white resort, he put up fences blocking residents from accessing the park and beach.

Founder Brumfield, an attorney, helped file a civil lawsuit. And in 1934, the judge sided with the community, saying that the beach and parks of Lake Ivanhoe were to be held collectively and kept open to everyone. The fence came down and Sternaman left the area for good.

Following World War II and against the backdrop of the civil rights movement, families like the Bakers rediscovered Lake Ivanhoe and slowly made it a year-round community.

‘An overlooked story that needs to be out there in the world’

Baker still lives in Lake Ivanhoe. He bought his parents’ home, eventually built his own and raised his family there. Now he’s president of the Lake Ivanhoe Homeowners Association.

But he says things have changed. A housing program in the ’90s brought in new families. According to the 2020 U.S. Census, the community is mostly white and Hispanic. African Americans make up only 9 percent of the population.

The lake needs dredging, and the beach road needs repair. The original families are long gone and with them the history of Lake Ivanhoe is fading away. That’s why Baker has been working for years to get a historical marker.

“It’s just kind of really hard to ignore this when you’ve got pictures and a community that (has) been here with the street names the way it is and everything else,” Baker said. “There’s no place else like this.”

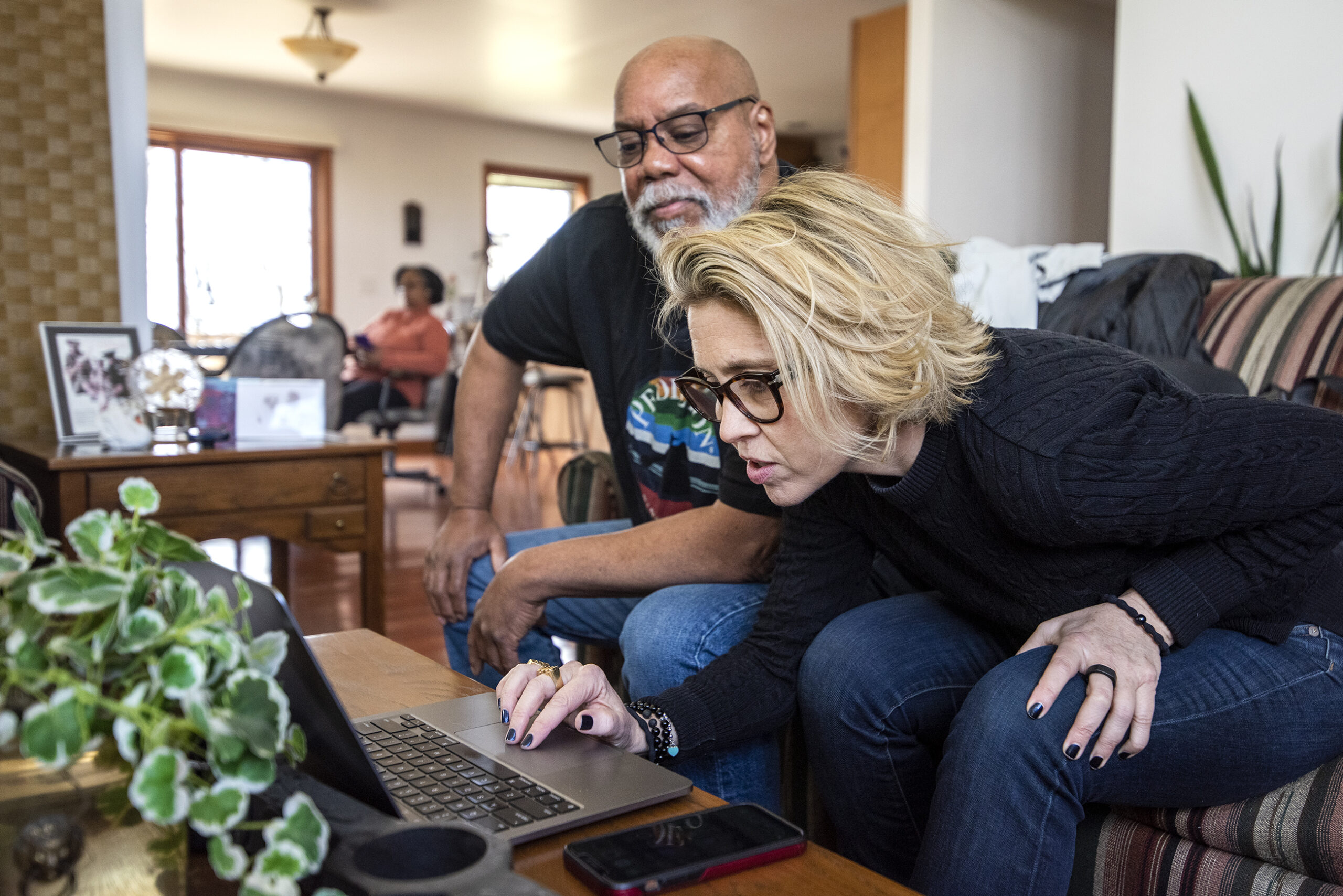

Recently, Baker has been getting help from Katie Green, whose family has owned a home 6 miles away in Lake Geneva since the 1970s.

But Green had never heard of Lake Ivanhoe until a few years ago, when a friend’s grandmother mentioned it.

“I had asked all my friends that I grew up with in Lake Geneva,” Green said. “I asked all my current neighbors, ‘Have you heard of Ivanhoe?’ ‘Nope. Nope.’ Nobody that I knew. So I started to dig into it.”

That’s how she met Baker.

“I called up Peter one day. He answered the phone … and we literally talked for an hour,” Green said.

Baker shared what he knew about Lake Ivanhoe’s history and Green said she was blown away.

“Just the vision of these men and their wives, their families, coming up here in the ’20s, in a place that was not welcoming to them. And they had the vision to create this community,” Green said. “It just feels like kind of an overlooked story that needs to be out there in the world.’”

‘So proud of that fish’

There isn’t much written about the history of Lake Ivanhoe. Most of what is known comes from a master’s thesis written in 1972 by Samuel L. Gonzalez, a student at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater. But Gonzalez died in 2013, and the people he interviewed are long gone.

So Baker and Green often spend their Saturdays combing through old documents and newspapers. They’re trying to collect artifacts and connect with past residents. They’ve started Facebook and Instagram accounts to help spread the word.

One of the people they found was Janet Alexander Davis. She and her family came to Lake Ivanhoe in the 1950s on fishing trips.

“We would go looking for worms, night crawlers, because that’s what we used to put on our hooks,” Alexander Davis said. “I remember one time I caught what they call a dogfish. That was the ugliest fish I’ve ever seen — ugly and big! But I was so proud of that fish.”

Alexander Davis hasn’t been back to Lake Ivanhoe since childhood, but she’s excited about the marker.

“I’m so glad they’re doing this. It’s proof that we were treated differently in this society and continue to be — that we had to find our own way and have our own things because we couldn’t just go where we wanted to go, to shop, to live,” she said. “So what I felt there was free.”

‘There’s nowhere else I’d like to be’

Later this summer, the two-sided historical marker sign will be installed beside the property owners association clubhouse, where the original pavilion once stood. Baker envisions kids coming to visit when they learn about Lake Ivanhoe in school.

Listen to Peter Baker read the text of Lake Ivanhoe’s historical marker.

“There will be pictures of that pavilion, there’ll be pictures of the kids riding their bikes and down at the lake, and they can go walk over there and actually see it and say, ‘Wow, that happened here,’” Baker said.

He’s already planning a dedication ceremony. He wants to invite past residents, have a pig roast and big band music, like the old days.

And he believes recognizing the community is the best way to start rebuilding it.

“I plan on being here for a long time, hopefully for the rest of my life. And I just hope it’s always a place that African Americans can feel safe in,” Baker said. “I literally am at peace here. There’s nowhere else I’d like to be.”

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this story referred to Lake Ivanhoe as the state’s first Black-founded community. The first Black-founded community in Wisconsin was the city of Chilton, which was first settled by Moses Stanton, a formerly enslaved African-American man, and his Native American wife, Catherine.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.