Conservative activists are pushing officials to remove thousands of people from Wisconsin’s voter rolls, pointing to holes in the state’s voter database that have allowed some ineligible voters to cast a ballot.

But their efforts also have spread misleading information, conflated ineligible and eligible voters and sown doubts about the upcoming midterms during a volatile time for American democracy.

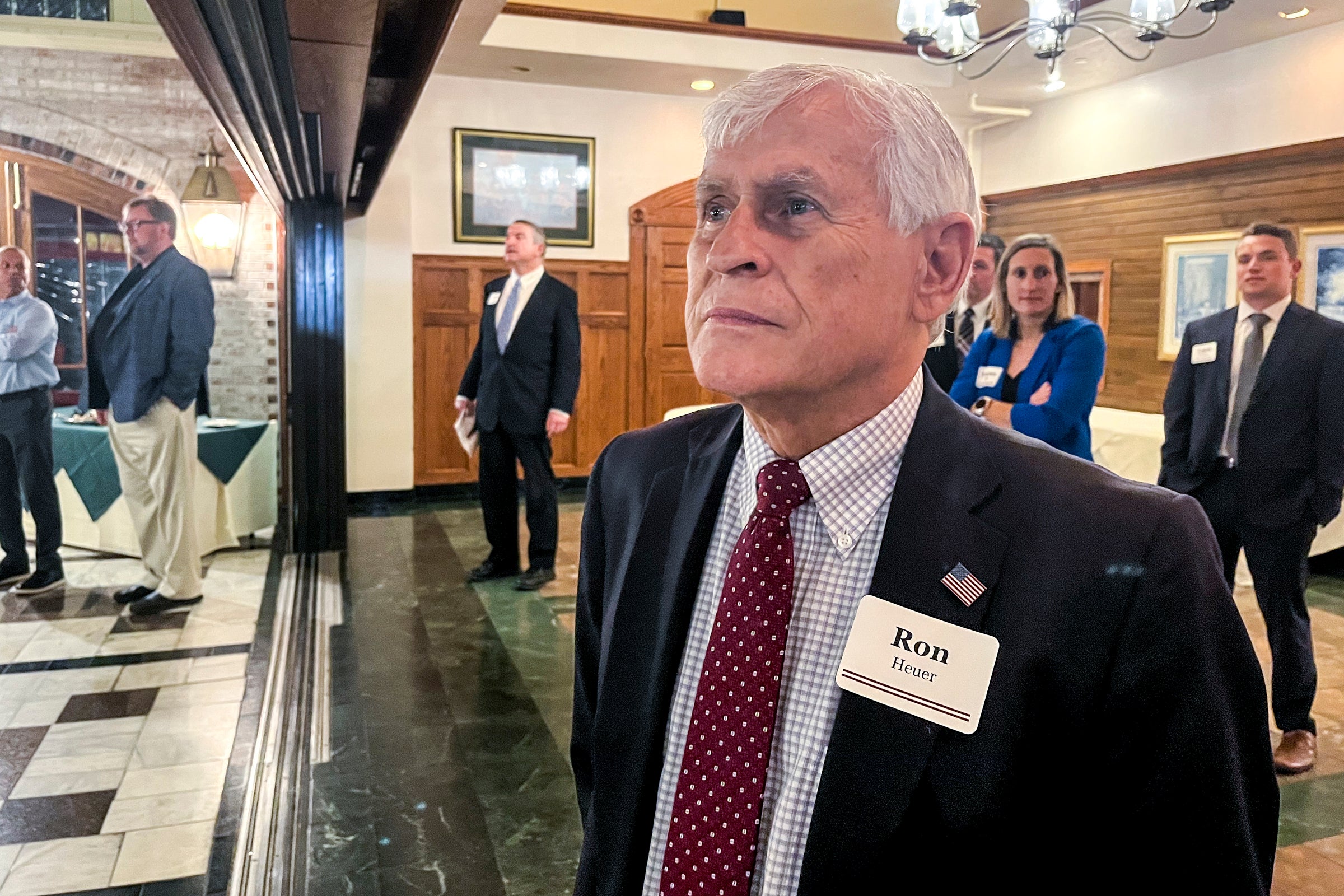

The activists include Wisconsin Voter Alliance president Ron Heuer, who worked on the more than $1 million taxpayer-funded 2020 election investigation that Republican Assembly Speaker Robin Vos shut down in August.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Heuer recently warned local clerks that the state’s election system is vulnerable because, by his estimate, there are potentially thousands of people under court-ordered guardianships whose votes could be fraudulently manipulated. He pointed to the case of an Outagamie County nursing home resident who voted in 2020, even though a court had ruled she was “incompetent” to vote months earlier.

A Wisconsin Watch investigation has found a yet-to-be-determined number of Wisconsinites whom a court has deemed incompetent to vote are still listed as active voters — and actually cast ballots in past elections.

Dane County Clerk Scott McDonell said he is reviewing the 1,013 ineligible voters in Dane County deemed incompetent after a sample of 20 included two who were still listed as active in the Wisconsin Elections Commission’s voter files — one of whom voted while ineligible in April 2019.

“We’re going to review our data and make sure it’s accurate,” McDonell told Wisconsin Watch.

The total is likely too small to have affected the 2020 election, in which 3.2 million Wisconsinites cast ballots.

It is certainly less than Heuer’s claim, which conflated people under a court-ordered guardianship, many of whom can vote, with the much smaller subset of those who lost voting rights. And the Outagamie case — while indeed an example of someone who shouldn’t have voted in 2020 — shows how administrative error is the likely reason ineligible voters cast ballots.

Still, Heuer’s work has already prompted officials to take action. On Oct. 3, the Wisconsin Elections Commission issued a guide to election clerks warning they cannot purge voters unless they find “beyond a reasonable doubt” a voter is ineligible.

Officials acknowledge gaps

WEC spokesman Riley Vetterkind acknowledged to Wisconsin Watch the system for tracking incompetent voters could be improved, although it would require legislation to ensure they are tracked the same as other ineligible voters.

The WEC also changed its voter data in August so the public can’t see names and addresses of those deemed “incompetent” — data that state law requires court officials keep private.

The conservative groups have sued to access guardianship name and address records in 13 counties. Heuer said their goal is to determine the true number of ineligible voters who cast ballots.

The push to purge voter rolls is the latest front by partisan activists who have relentlessly challenged the 2020 election and now may be trying to create grounds to dispute future elections, according to David Becker, a non-voting board member of the nonpartisan Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC), which Wisconsin and 32 other states use to maintain their voter rolls.

Think tanks on the left and right agree there is little fraud in U.S. elections. The conservative Heritage Foundation, which tracks “proven” cases of election fraud nationwide, found four instances of fraud in Wisconsin in 2020.

Becker said age-old attempts to “artificially inflate” voter list accuracy bring more risks in the current climate.

“When tensions get as high as they are, when grifters have been incentivized to keep the anger going to keep donations flowing in, then you get a very, very dangerous situation,” he said.

Number of incompetent voters disputed

On Sept. 27, Heuer emailed the state’s more than 1,800 clerks warning there are some 15,000 Wisconsin residents under a court-ordered guardianship, but fewer than 1,200 listed in WEC’s voter roll file as incompetent. Heuer concluded the true number of incompetent voters is underreported and thus the whole system is vulnerable to “elder voting abuse.”

But the information he cited was misleading.

The voter roll data file is a constantly updated public record with voter names and addresses. Heuer obtained a version of the file with about 1,200 names and addresses of voters listed as “ineligible” and the reason “incompetent.”

He found several counties had zero ineligible voters listed as incompetent, which Heuer said county officials told him was incorrect.

He then requested guardianship numbers in each county between 2016 and 2021. Based on responses from about a third of the state’s district courts — and using a per capita projection — he came up with the 15,000 estimate.

However, the numbers Heuer used include everyone placed under a guardianship — even though not all of them have lost their right to vote. Also, some are deceased and some may never have been registered to vote, so they don’t appear in the public voter roll file.

McDonell told Wisconsin Watch there are 1,013 people from Dane County listed as incompetent in the WEC’s files since 2007, including 75 marked in the voter file as inactive. In the sample of 20, he found eight had never registered, one was inactive and marked incompetent, nine were inactive for other reasons — such as being deceased — and two were active, including the one who voted. That person was adjudicated in November 2018 and voted in April 2019, but has not voted since, McDonell said.

WEC keeps incompetent voter data in a non-public file where local clerks can review it periodically to update registration information, Vetterkind said.

“It is possible you may find voters who, despite being adjudicated incompetent by a court, registered, continue to be registered, or voted in an election(s),” Vetterkind said, although he declined to estimate how many. “These cases are unfortunately a product of the limitations that state law currently places on the process for centrally compiling adjudicated incompetent records.”

Possible out-of-state movers targeted

Other groups are also pushing clerks to purge voter rolls. In September, Wisconsin clerks received an email that claimed about 47,789 people had moved out of the state but, according to Peter Bernegger, of the Wisconsin Center for Election Justice, were still active voters.

Bernegger asked clerks around the state to mark those who had left the state as “inactive” on the voter rolls. In his email, which Wisconsin Watch obtained, he said he used WEC and the U.S. Postal Service’s change of address data to find voters who should be removed.

Simply relying on something like the USPS database, which is optional and doesn’t include someone’s date of birth, to identify people who moved is problematic, said Becker, the ERIC board member and executive director of the Center for Election Information and Research.

ERIC identifies voters who have moved out of a state and therefore are no longer eligible to vote there. But, he added, each state then relies on its own laws and policies before a voter is removed. In Wisconsin, local clerks contact voters directly to see if they’ve actually moved.

Becker added that every state inevitably has voter lists that include people who are no longer eligible and exclude eligible voters. But he emphasized that very few ineligible voters are knowingly or unknowingly voting illegally.

“That number is not zero, but it’s really close to zero,” Becker said. “It’s remarkable how close it is to zero.”

Bernegger acknowledged in his September email to clerks that not all 47,000 people he found had definitely moved and were no longer eligible voters. Bernegger and his attorney did not return messages seeking comment.

Bernegger previously filed complaints with the WEC about voters using UPS addresses to vote, but the agency dismissed them as “frivolous” and fined Bernegger $2,400, which he has not paid.

Incompetent voter case fuels suspicion

One of the factors driving the activists is that they have found at least one case of an improper vote being cast in 2020 — although a closer look at the circumstances in that case points to administrative error.

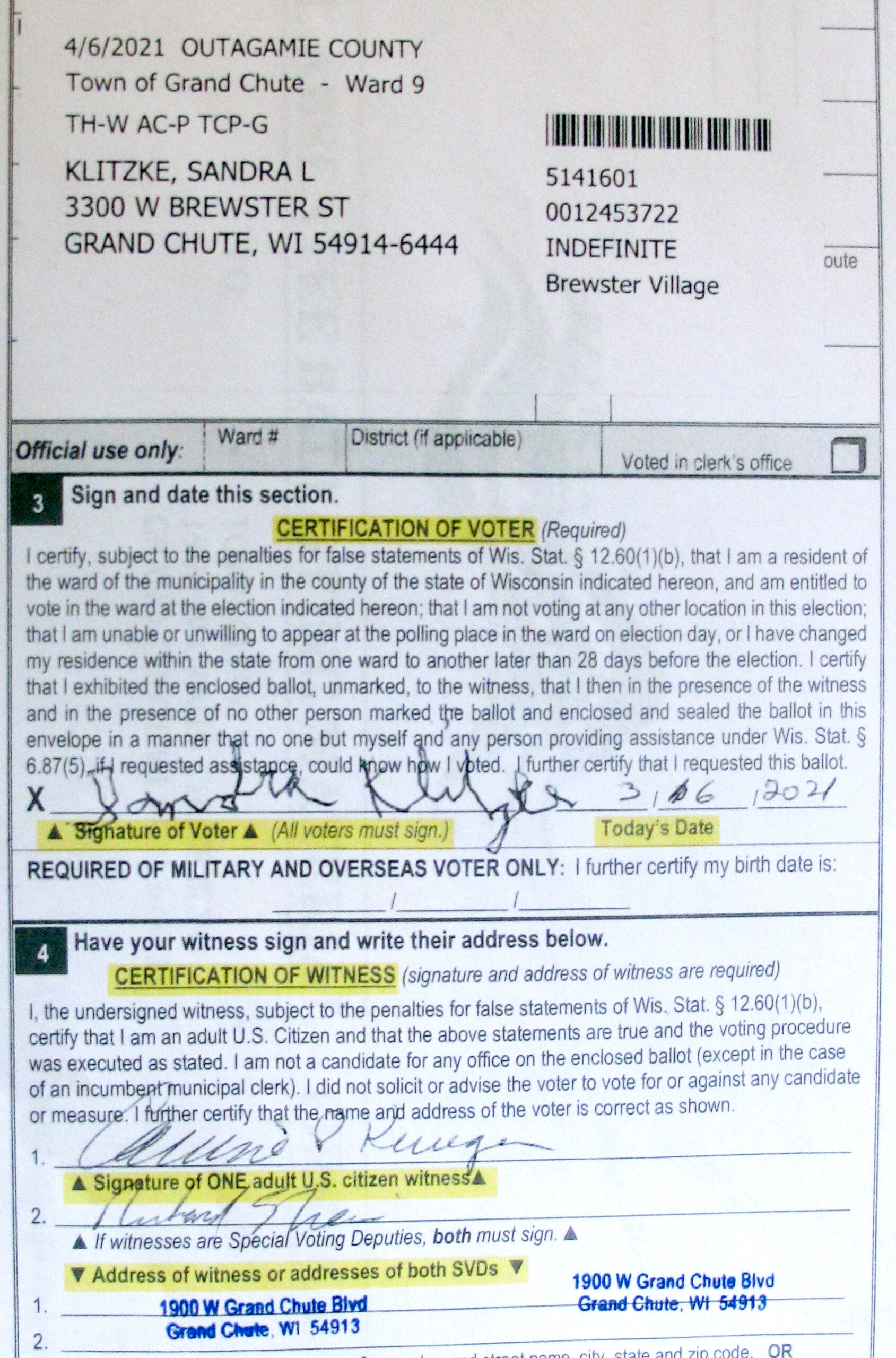

The case involves Sandra Klitzke, a resident of the Brewster Village nursing home in Outagamie County, who had voted in the November 2020 and April 2021 elections, even though a court had removed her right to vote in February 2020.

On March 31, the Thomas More Society filed a WEC complaint on behalf of Klitzke and her daughter, Lisa Goodwin, who stated she “could not explain why the WisVote voting records would have indicated that my mother voted” in 2020 or 2021.

Normally the county register in probate mails notification of an ineligible voter to the WEC, according to Jennifer Moeller, president of the Wisconsin Register in Probate Association. The WEC then updates its information and notifies the local clerk, who is the only official authorized in Wisconsin to deactivate a voter’s registration.

Klitzke case points to error

It’s unclear why Klitzke’s name was not switched to “ineligible” in the WEC voter file. Both the WEC and Outagamie County officials said court records related to Klitzke’s guardianship information are confidential under state law.

Town of Grand Chute Clerk Kayla Filen, who was not clerk at the time, confirmed her office did not deactivate Klitzke’s registration until April 2022.

Klitzke had been registered as an indefinitely confined voter dating back to 2007 and had voted as recently as 2017 before the 2020 election, Filen said. Indefinitely confined voters automatically receive absentee ballots without having to request them, Filen said.

A Wisconsin Watch review of Klitzke’s absentee ballot envelopes from 2020 and 2021 show them both signed in a shaky hand. In the 2020 election — when the WEC suspended the state’s special voting deputy program in nursing homes because of the pandemic — an employee at the county-owned facility had signed as a witness.

In 2021, two witnesses from the town of Grand Chute signed the envelope, reflecting the normal process of special voting deputies witnessing nursing home voting.

Heuer said “many” people have come forward with stories of loved ones with cognitive disabilities voting. His group has filed public records lawsuits in Brown, Crawford, Juneau, Kenosha, Lafayette, Langlade, Marquette, Ozaukee, Polk, Taylor, Vernon, Vilas and Walworth counties to obtain the names and addresses of everyone under guardianship.

Disability Rights Wisconsin opposes the release of the names of incompetent ineligible voters and lobbied WEC to shield them in the public voting file, said Barbara Beckert, Disability Rights Wisconsin’s external advocacy director.

During the pandemic, Beckert said her organization reminded nursing homes across the state that federal guidelines require them “to affirmatively support the right of residents to vote.”

“Why aren’t we concerned about the vast majority of people who live in these facilities who have the right to vote and who might not be able to exercise it?” Beckert asked.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.