Months before hospitals cautioned that fast-spreading variants of COVID-19 could overwhelm facilities, there were signs Wisconsin’s usually high-performing health care system was under strain.

In October, Jeannine Combs went to the emergency room with her husband Douglas, who was having chest pain after having open-heart surgery in 2018. Nearly an hour later, he was seen by a doctor. It would be three hours before he was admitted to Mercyhealth Hospital in Janesville. The couple was told the hospital was treating a lot of COVID-19 patients and there weren’t any beds immediately available for Douglas.

“That is so unacceptable and dangerous for a patient with chest pain, and as a spouse, so heartbreaking to watch as your loved one is not getting the care they so desperately need,” said Jeannine, who contacted WPR’s WHYsconsin. Both she and her husband used to work as nurses.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

A day after being hospitalized, Douglas, 65, had a cardiac catheterization. During the procedure, his heart stopped beating, Jeannine said. After the surgery, Douglas was supposed to recover in an intensive care unit, but there were no open beds so he went to a different medical unit.

“I cannot place any blame on these nurses. They are doing the very best that they can. I know, I’ve been there,” said Jeannine, who cared for AIDS patients in San Francisco during the 1980s and ’90s. Her husband worked as an ER nurse in a Madison.

Douglas survived.

Not everyone does.

The winter surge

Today, there are nearly twice as many people hospitalized with COVID-19 in Wisconsin as there were when Combs was hospitalized.

This month, Wisconsin repeatedly broke records for the most COVID-19 infections in a day, and saw more patients hospitalized with the disease than at any point in the pandemic. It’s not where anyone — health professionals, public health experts or policymakers — expected us to be nearly two years after COVID-19 appeared in the state.

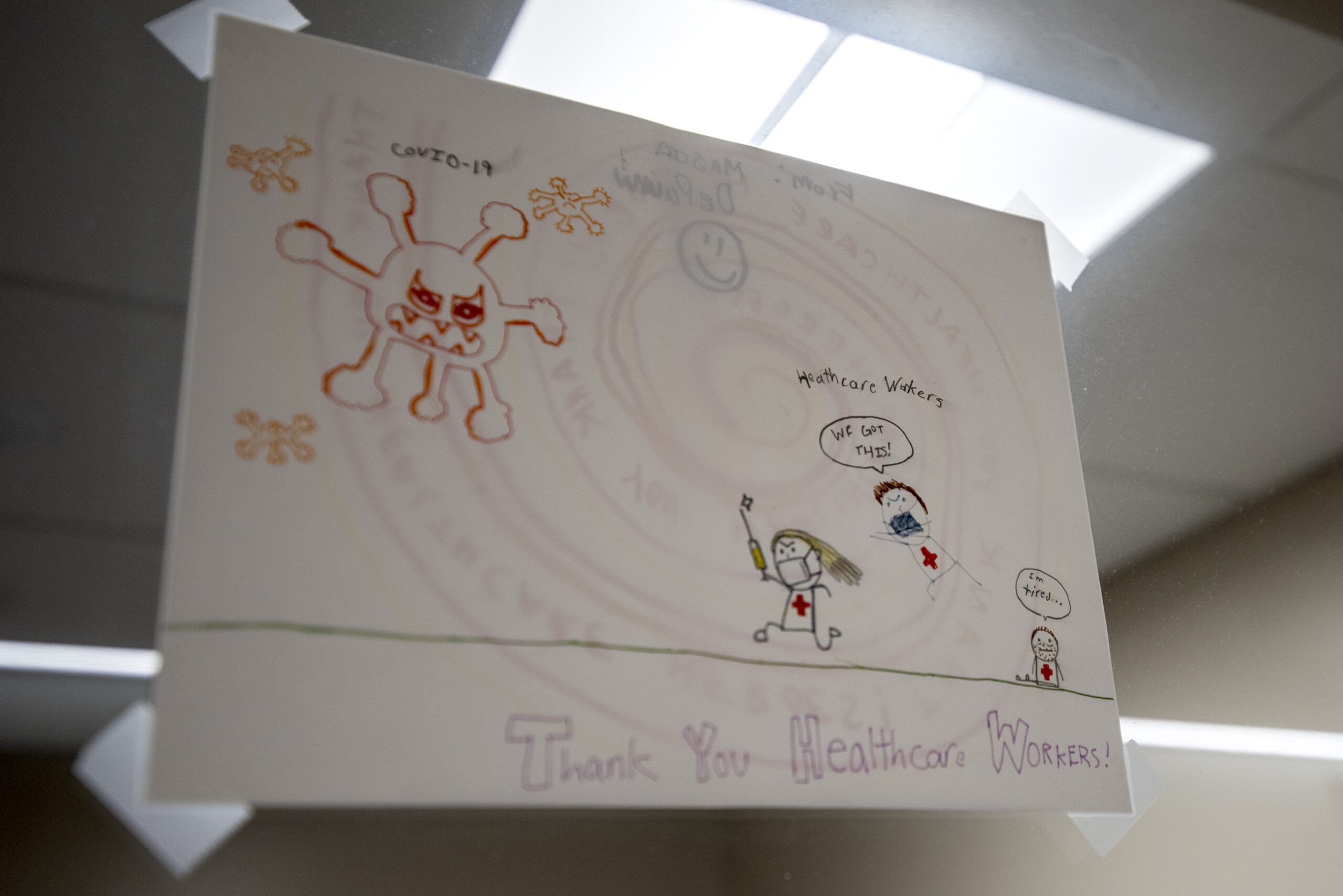

The outcome of patients across the country depends not only on the condition they have, but also their health and the care they receive. In a widely shared social media post before Christmas, a longtime ER nurse at University Hospital in Madison described in stark terms how the facility was overflowing with sick — and mostly unvaccinated — COVID-19 patients and the toll it takes on staff and other patients.

“I know that sometimes when I say goodbye to these people, I’m never going to see them again. Because they’re going to die. They’re never going to make it out of this place,” the nurse, identified only as Sue, said. “It’s hard. We have nurses leaving this profession. They’re burned out. They’re overworked.”

“Please, please get vaccinated.”

Sue, a nurse in the Emergency Department at University Hospital for 20 years, shares her raw emotions about working in a hospital overflowing with sick and unvaccinated patients. pic.twitter.com/qxkX2Z8Wz2

— UW Health (@UWHealth) December 22, 2021

Last winter when hospitals were contending with their highest surge in cases yet, phrases like “light at the end of the tunnel” gave a sense of optimism and the public was schooled in how to “flatten the curve” as we waited for vaccines to be approved and made widely available.

Since then, cases have risen and fallen several times. There are more treatment options for those infected with COVID-19, and 59 percent of Wisconsinites have completed their vaccine series to help prevent serious infections. At the same time, though, pandemic precautions like mask-wearing and avoiding crowds have largely become a thing of the past.

The path out of the pandemic, once seen as a straight shot, takes many detours

In December 2020, after vaccines were approved but before they became widely available, Dr. Neil Bard was hopeful. The medical director at Richland Hospital Clinic in southwestern Wisconsin still remembers polio.

“People got paralyzed from polio,” Bard said. “I remember being taken by my parents — rushed — to the local elementary school, and we couldn’t wait for the public nurse to vaccinate us.”

Some people reacted the same way when the COVID-19 vaccines became available. Between December 2020 and May 2021, 5.3 million doses went into arms in Wisconsin, according to state data. But others still haven’t rolled up their sleeves.

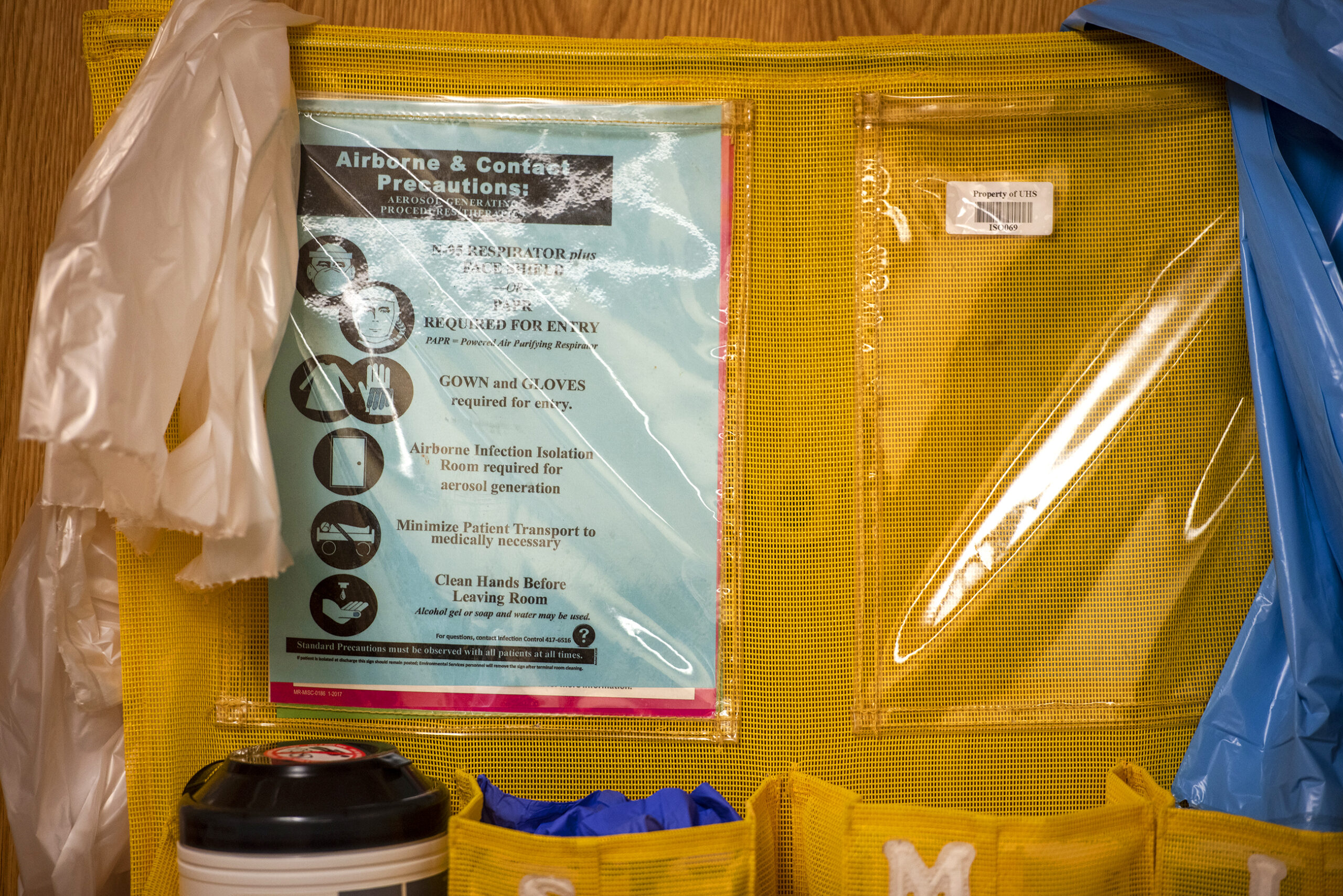

The omicron variant has led to more breakthrough infections among vaccinated people than previous strains of the virus, but the unvaccinated are still the overwhelming majority of severe cases. According to state data, unvaccinated Wisconsinites were 10 times more likely to be hospitalized than those who had been vaccinated. That has filled hospital beds others might need.

“There’s delay in treatment for cancer, there’s delay in treatment for heart disease that I know personally has happened in my patients because the specialty beds in hospitals in Madison and La Crosse are full,” Bard said in mid-December, when the surge was just starting to gain steam.

The pandemic has defied predictions and has left many to feel like there are no easy answers.

In Madison, Dr. Christopher Lowry has been working with COVID-19 patients since the spring 2020. Like many, he never expected the pandemic to last this long.

“I think everything about the situation has been unpredictable,” he said. “And as things have gone on, it’s been one revelation after another as to what we’re dealing with. And it’s getting harder to predict.”

Lowry went into medicine because he liked problem-solving and figuring out how best to help patients. With limited treatments for COVID-19, he said the science isn’t hard — it’s the social aspect that’s taxing.

“I think it’s draining (health professionals) drive to continue on. I think it’s affecting their compassion. It’s the same situation over and over. The hardest part is knowing this could have been prevented,” he said of largely unvaccinated patients.

Getting back to normal

Outside the walls of a hospital, it can be hard to tell we’re in the midst of a pandemic.

The most obvious sign this winter is different from last is holiday travel. It’s usually the busiest time for airports. But in 2020, many passengers decided to stay home. Not in 2021. Two days before Christmas, the Dane County Regional Airport, like many others around the country, was bustling.

People eager to reconnect with faraway family and friends shuffled through airports and onto planes with carry-ons and children, just like they did before the pandemic. With one difference: masks, which weren’t required by the federal government or air travel until President Joe Biden took office in January 2021.

For some people, the holidays were the first time in years they had seen family members. There was a nationwide scramble for scarce at-home tests as people prepared to travel and waited hours in line for PCR testing.

But for some, this stage of the pandemic has also caused a sort of resignation or even fatalism about the course of the virus.

“We all know at some point, we’re all going to end up getting it,” said Toni Barghout, of Fitchburg, who was having her 5-year-old daughter tested for COVID-19 at a pharmacy Dec. 21 before a family gathering.

Masks on, masks off as COVID-19 repeatedly surges and recedes

Before the holidays, hospitals and public health officials used words like dire and dangerous to describe how skyrocketing COVID-19 cases could affect medical care for everyone

It was a familiar message.

A full year earlier, hospital staff around the state wrote an open letter to the public, pleading for people to take the pandemic more seriously. At the time, the only tools against the pandemic were social distancing and masking. Doctors like Ann Sheehy at UW Health were hoping people could hold out until vaccines came along.

“We really intended this to be a message of unity and compassion and teamwork as opposed to telling people what to do or what not to do,” Sheehy said in December 2020. “Obviously, we included our recommendations in that document, but I don’t think people are responding to a message of scolding.”

Open letters, even full-page newspaper ads, asking the public to help combat COVID-19 have recently been used by hospitals in Milwaukee and Cleveland. Their request? To get vaccinated. To get booster shots. To wear a mask. To stay home if sick and get tested.

To date, more than 10 million shots have gone into the arms of Wisconsin residents, but vaccination remains too low to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and mask-wearing has dropped off.

Dane County is one of the last communities in Wisconsin to require masks indoors, and the Wisconsin Supreme Court has agreed to hear a challenge to that mandate. Before the court accepted the case, people packed a rural town hall for a hearing organized by Dane County supervisor Jeff Weigand, who said he wanted people to be able to publicly share how the indoor mask mandate has affected their families, schools and businesses.

“COVID is real and many of us have been impacted by it,” Weigand said at the hearing. “Some of us have gotten it; family members might have passed away. This is a real thing. But I’m not going to live in fear because of a virus.”

Jeffrey Horn, of DeForest, was at the meeting. Like most others in attendance, he didn’t wear a mask. He said in October 2020, he had a mild case of COVID-19, which he treated at home.

“I didn’t take any ivermectin or hydroxychloroquine,” Horn said, referring to forms of treatment that have become articles of faith among some conservatives despite no evidence that they are effective. “I just mean the kinds of thing you would do if you had a bad case of the flu: keep yourself hydrated; I did take some vitamins; rested a lot.”

The Food and Drug Administration has cautioned that current studies don’t show ivermectin is safe or effective for treating COVID-19, but it became so widely used for that purpose that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued an emergency alert in August urging people to not use the medicine meant to treat parasitic infections.

Horn, who has organized protests against other pandemic precautions, believes natural immunity is society’s way out of the pandemic. Studies, however, show natural immunity to the coronavirus weakens over time, and does so faster than immunity provided by COVID-19 vaccination.

Additionally, Epic Health Research Network has found unvaccinated patients are 44 percent more likely to be reinfected with COVID-19 than those who are vaccinated against the illness.

With hospitals full and staff drained, health officials have said everyone who may need medical care is at risk — not only those ill with COVID-19, but people like Douglas Combs who needed emergency attention. In a statement, Mercyhealth said escalated COVID-19 volume in the community increases the likelihood of a delay for medical care, something state Department of Health Services Secretary Karen Timberlake didn’t sugarcoat during a Jan. 13 media briefing.

“The risk to our communities has never been more dire,” she said.

January showed us the pandemic is not over. Officials say it’s still too soon to tell whether the latest wave has peaked.

This week, WPR and WHYsconsin are bringing you stories of the way the pandemic has affected us. They include people who have lost family members, those who’ve lost jobs or changed careers, and patients and health care workers facing overburdened hospitals. For more stories on COVID-19, visit wpr.org/COVID.