The University of Wisconsin-Madison has joined an international effort to create a pandemic prevention institute aimed at helping researchers, public health officials and governments respond quickly to future pandemics.

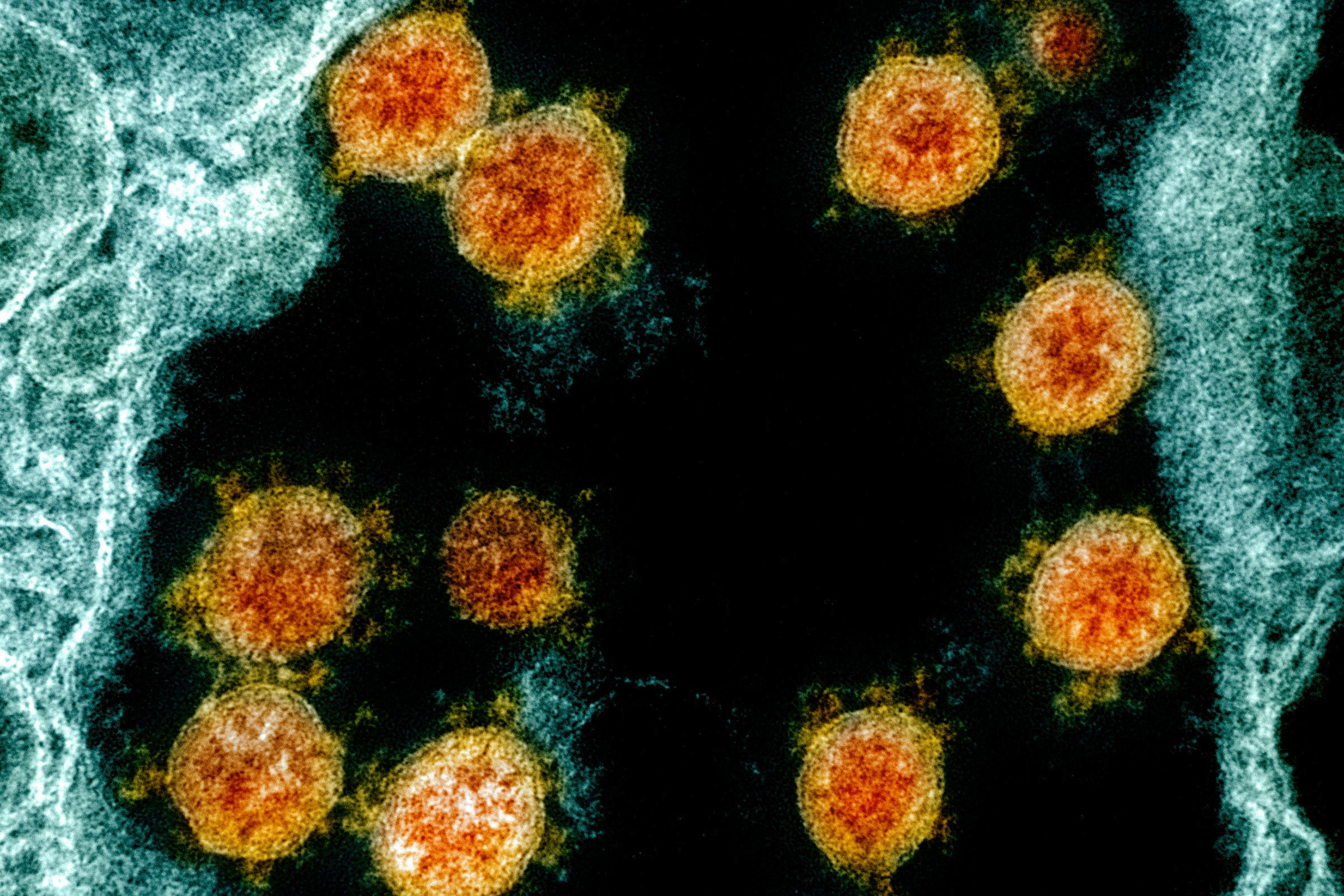

The Pandemic Prevention Institute is being funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, a philanthropy organization. By expanding genomic sequencing of viruses, improving collaborations between university researchers and health officials, and studying new disease surveillance technologies the world will be better prepared when a new virus like the one that causes COVID-19 appears, according to the institute’s website.

UW-Madison professor of virology, Thomas Friedrich, said the campus is one of four universities in the United States receiving funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. He said UW-Madison is getting around $350,000, and about half of that will go toward increasing partnerships between researchers and public health departments at the national, state and local levels.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“The goal is to take advances in genome sequencing technology that we and others have been applying to understand how the coronavirus is spreading and make those advances more directly applicable to public health,” said Friedrich.

Shelby O’Connor, an associate professor at UW-Madison’s Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, said she and other researchers love spending time in the lab but could learn better ways of communicating their science to public health agencies.

O’Connor said one of the challenges with sharing real-time data between public health and scientists doing genetic sequencing is adhering to medical privacy laws. If researchers are able to get more information about where virus samples are coming from, it would enable them to more accurately track disease progression in communities, she said.

“But trying to get that information in an appropriate manner to abide by all the regulatory procedures takes a lot of effort,” said O’Connor. “And so, these silos tend to emerge because crossing that barrier is really difficult.”

The Rockefeller initiative is also helping researchers in different fields, like aerosol biology and virology, get in the habit of having conversations they didn’t before, said UW-Madison virologist Dave O’Connor said.

Part of the grant money will go toward researching new ways of detecting viral transmission without invasive nasal swabs, like those used during the coronavirus pandemic.

“I had the idea, wouldn’t it be great to be able to suck a virus out of the air?” said Dave. “And that led me to learn about the research that other people were doing in this field.”

Dave said he found companies that design air samplers, which can collect viruses in a filter, for scientists to run genetic sequencing on.

Researchers in Australia are in the early stages of testing how accurate air samplers are in detecting airborne pathogens, and Dave keeps in touch with those researchers.

“It’s the sort of thing you put in the sort of arena, or you put it in the Kohl Center, you put it in schools or transport hubs, and then you have the ability to determine what sort of viruses are circulating,” said Dave. “It’s science fiction until it isn’t.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.