(See more interviews with this author at the end of this article.)

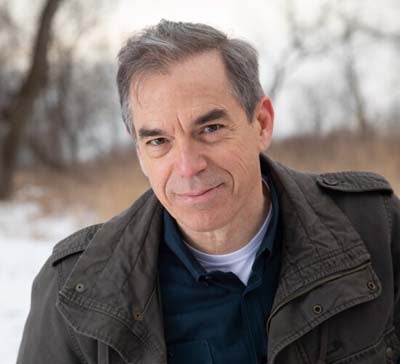

Miles Harvey is the author of “The King of Confidence.” In the summer of 1843, James Strang, a charismatic young lawyer and avowed atheist, vanished from a rural town in New York. Months later he reappeared on the Midwestern frontier and converted to a burgeoning religious movement known as Mormonism. The author is interviewed by WPR’s Norman Gilliland. “The King of Confidence” will be read by Gilliland on Chapter a Day starting Monday, November 2.

· James Strang was a failed attorney and avowed atheist, who convinced a lot of followers that he was the hand-picked successor of slain Mormon founder Joseph Smith. To what extent was his rapid rise a product of the frontier?

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

He arrived in Wisconsin, in 1843, five years before the territory received statehood. Back then, the place was still at the far edge of the country and considered the American West. (The region wouldn’t become known as the “Midwest” for another half century.) In this transitory world, beyond the reach of normal societal rules and largely beyond the reach of the law, someone like Strang could shed his past and transform himself into a new being. In the East, he had been a failure as both a lawyer and newspaper editor. He had been fired as a postmaster. He had amassed big debts, and according to one report, he had faked his own death in order to flee his creditors. But in less than a year, he was claiming to be a prophet of God and the rightful heir to the leadership of the Mormon church and its 25,000 members—by any standard, a remarkable metamorphosis.

· What induced Strang to join the Mormon church?

That’s the million-dollar question. He was an intellectually curious man, so he may have had some sincere interest in this dynamic new faith. He was also going through a personal crisis, having just lost his five-year-old daughter to one of the 19th century’s many fatal illnesses, so he might have been in search of answers and solace. But according to one of his associates at the time, Strang’s interest in the church was part of a simple real-estate swindle, designed to lure Mormon pilgrims to the town of Burlington, where he and his friends owned land.

· In what ways did he distance himself from it—and vice versa?

Most leaders of the church were quick to distance themselves from Strang. Brigham Young, who from the start seems to have recognized the newcomer as a serious threat, branded Strang an “evil liar” and urged Mormons to “save yourselves from the snare of deception of the Devil.” But many members of the faith were by that time disillusioned with Young and other church leaders for engaging in polygamy—a practice that, while not officially acknowledged, was widely known about the main Mormon city of Nauvoo, Illinois. Strang, by contrast, set himself up as the anti-polygamy candidate. “My opinions on this subject are unchanged, and I regard them as unchangeable,” he wrote in 1847. But J.J. Strang was not a man to stick to his promises. Just two years later, he secretly took his first plural wife.

· He was very convincing when he preached to potential converts. How much of what he said did he believe? Was there a point at which he was simply delusional?

I’ve come to believe he had a kind of double consciousness. On the one hand, he must have known that he was making up wild fictions and misleading great numbers of people. Even as a young man, after all, he had boasted in his diary about a unique ability to “pray and talk about religious subjects” in public, while keeping secret the fact that he was a complete atheist. But on the other hand, I suspect Strang also came to see himself as a savior—which, in his mind, allowed him to operate by a different set of moral rules than other people. My hunch, in other words, is that he was not unlike President Trump, who tells countless lies but only seems to really believe one of them—that, as he famously put it, “I alone can fix” the nation’s problems.

· Islands are good places for setting up an independent style of living. But Beaver Island, as you point out, could get down to 30 below zero. Did Strang have any idea what he was getting himself and his followers into when he moved them there? Did he have a plan for survival?

Well, he may have come to believe that God was on his side and would somehow keep his people safe, but he was also a very shrewd and practical man. A big part of his plan for survival involved theft and plunder. In THE KING OF CONFIDENCE, I argue that Beaver Island basically became a pirate colony, with Strang sending out ships to attack coastal towns as far south as Chicago and dispatching gangs all over the Midwest to steal horses and other commodities. Some previous historians have doubted this idea, with one of them insisting that “a great amount of unfavorable public opinion about the Beaver Island Mormons was moulded by nineteenth century feature writers from semi-truths and fabrications gleaned from completely biased Gentiles who hated them.” This author was right about the anti-Mormon bigotry, which was sadly rampant in that era, but he was wrong about the supposed innocence of the islanders. In researching this book, I was able to document not only vague accusations against Strang’s followers, but actual arrests and convictions of those caught red-handed. I was also able to place Strang himself at the scene of a jailbreak of one of his top lieutenants, who had just been convicted of horse theft.

· What sort of person made a likely convert to Strang’s cult?

Like the current moment in history, the mid-19th century was a time of dramatic change—economic, social, political and technological. And as with the present age of pandemic anxiety, people faced profound existential worries. The Irish potato famine, which was exploding right as Strang rose to prominence, killed more than a million people and prompted another two million to flee their homeland, more than half of them to America. At the same time, cholera and other epidemics were causing tens of thousands of deaths in the United States. In response to these very complicated and very horrifying realities, Strang offered very simple and very comforting solutions. The motivations of his followers were no doubt various and complex, but many of the true believers were people who felt a profound sense of loss, alienation and terror due to the upheavals of the antebellum era.

· Did he lose anyone when he had himself crowned as “divine king of earth and heaven?”

In the aftermath, of Joseph Smith’s murder, Strang attracted some of the top leaders of the Mormon church to his side—including, for a short time, the late prophet’s own brother. But many of those people quickly soured on him. One church official named Reuben Miller, for example, initially became so enthralled with the upstart prophet that Brigham Young found him to be “almost devoid of reason.” Miller followed Strang to his first utopian colony in Burlington Wisconsin, rallying other true believers to join him there, but he soon had a change of heart, especially after Strang started holding secret conclaves in which followers pledged their loyalty to him as the “actual Sovereign Lord and King on Earth.” Strang’s church, Miller eventually concluded, would go “down on the pages of history as a monument … of the corruption and wickedness of the human heart.” Instead of leaving town, however, Miller and other former members of the flock stuck around and made trouble for the prophet—no doubt one of the reasons Strang decided to move the sect north to Beaver Island. In that isolated place, it was

easier to keep enemies from coming in and followers from going out. Nonetheless, many disaffected members did leave. But right up until his death, Strang demonstrated an almost uncanny ability to replenish the ranks by attracting new converts.

· Who were his lieutenants and what were their motivations?

Many of Strang’s followers were, of course, people of sincere faith. But along with those true believers were what one 19th century chronicler called “unprincipled men,” who came to Beaver Island for “the opportunities it afforded for unbridled license under the pretended sanction of religion.” One of the most fun things for me about working on this project, in fact, was to write about all the colorful con artists who found their into the prophet’s inner circle. Perhaps my favorite was George J. Adams, a legendary figure who split his time between proselytizing and drinking, performing Shakespearean tragedy and drinking, preaching abstinence from alcohol and drinking. Oh, and womanizing. And talking people out of their money. And … well, let’s just say that I agree with one contemporary newspaper’s assertion that he was “the most consummate, bold and plausible deceiver that ever went unjailed.” At least one scholar, in fact, has argued that Mark Twain, who wrote about some of Adams’ later exploits, may have used this notorious swindler as his model for the King, the inebriated con artist and itinerant actor in Huckleberry Finn.

· And his “nephew” Charley—what was her role?

Ah, yes, Charles J. Douglass—he (or, as you more correctly put it, she) was one of the other great stranger-than-fiction figures of the story I tell in THE KING OF CONFIDENCE. In 1849 and 1850, Strang toured the East Coast for months, introducing this young man as his 16-year-old nephew and private secretary. But in fact, Charley wasn’t a man at all. His real name was Elvira Field, and she was Strang’s 19-year-old wife in men’s clothing—a secret the prophet hoped to keep from his other wife. Strang had five wives by the time disaffected followers assassinated him in 1856—a rebellion prompted in part by his decree that all women on the island must wear pantaloons. The surprisingly complex gender politics of Strang’s colony—and of the antebellum era in general—were among the most fascinating aspects of researching and writing this book.

· What’s Beaver Island like today?

It’s a beautiful place—and in many ways still pretty wild. The vast majority of the roads, for example, remain unpaved. One notable exception is King’s Highway—named after Strang, who ordered his followers to cut this straight-line thoroughfare into the forest. Although almost none of the structures from Strang’s time are still standing, he and his followers have left their mark on the island through the many place-names they came up with, including that of St. James, the only real town. When my family and I visited, we stayed at the opposite end of the island from St. James, near where some of the prophet’s enemies once holed up. It’s pretty isolated there. We were out of cell-phone range and had no internet, which did not please my teenage children. But one night my wife and I lay out on our balcony and watched a meteor shower in the dark sky, a truly spectacular experience.

· What are you working on now?

At the moment, I’m writing a lot of fiction. After finishing a project that involved so much factual research, I’m cherishing the chance to dream up my own little worlds. Of course, when it comes to inventing reality, I can never compare to that great master of American fabulism, James J. Strang

Doug Gordon’s interview with author Miles Harvey for BETA

Video of full interview with author Miles Harvey at the Wisconsin Book Festival

Note: You will be asked by the library’s website to submit your email prior to viewing the video.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.