In 1999, Ann Marsh was cleaning out her house in Florida when a brown recluse spider slipped up her pant leg and bit her on the ankle.

The venous bite nearly cost her her leg.

This experience might scare most people away from seeking out insects and other creepy-crawlies, but not Marsh. After a two-year recovery, she left her 26-year career in retail and started working in insect labs and pursuing a doctorate in entomology. She now spends many of her days wandering Wisconsin’s wetlands to study insects up close.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I figure that’s like the worst of the worst,” she told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” about her close call with the spider. “Brown recluse spiders typically don’t live here in Wisconsin, and if they do, they don’t have venom that’s that potent.”

Today, she studies an industrious family of insects in wetlands called Staphylinidae. These are composting bugs, most of which are just 2 to 4 millimeters in size, that help break down organic matter including leaves and small animals.

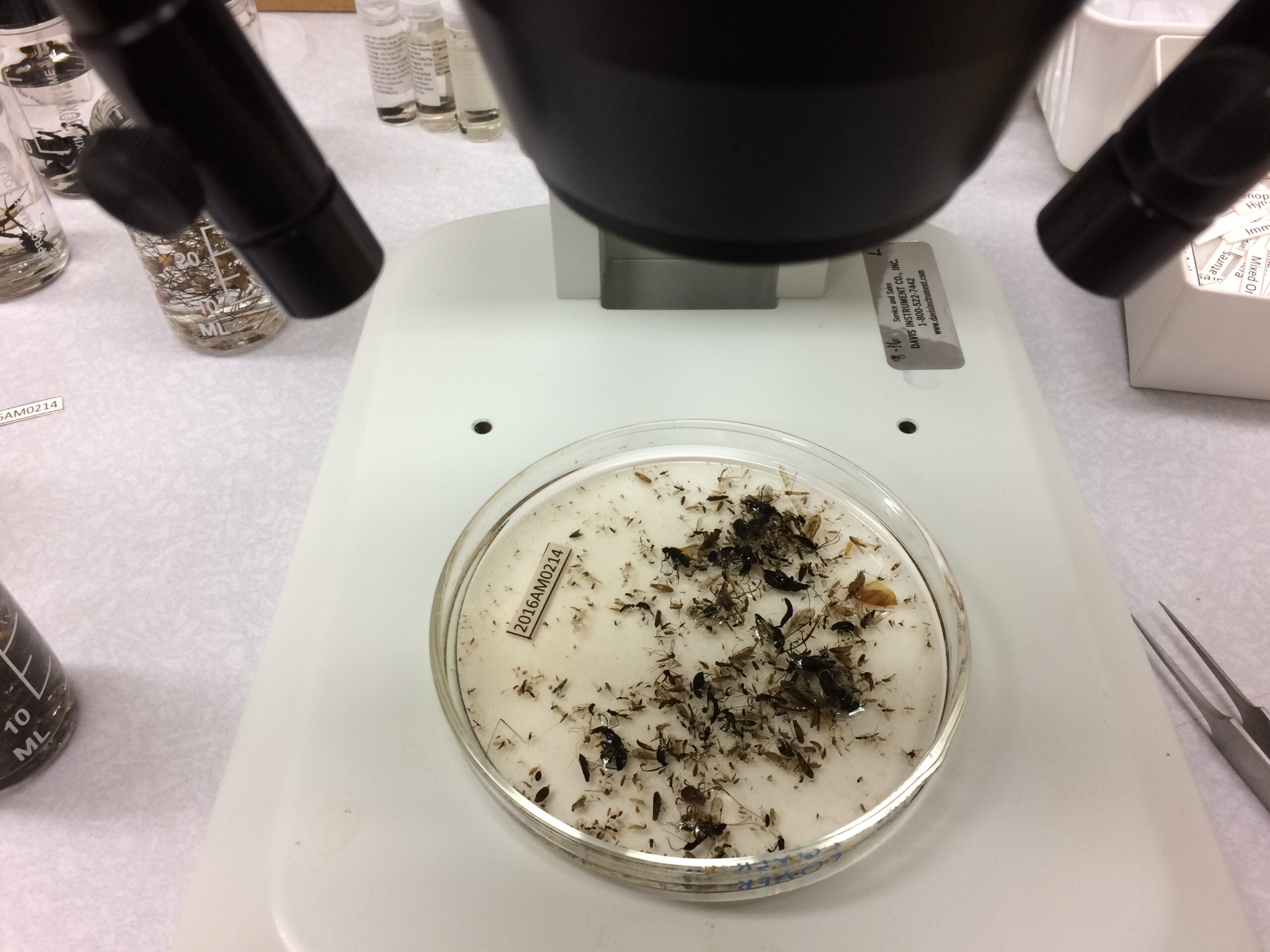

As a University of Wisconsin-Madison graduate student studying taxonomy and systematics, Marsh categorizes insects. Examining the insects with a microscope, she divides them into species, which is the smallest grouping of an insect. Those species could be classified simply by the number of hairs that are on their wings or the shape of their abdomens.

“I love to organize,” she said.

Twenty to 30 percent of all Canadian and American insects can be found in Wisconsin, Marsh has found. Yet, prior to 1997, Wisconsin’s insects had never been systematically surveyed.

She’ll be giving a talk at the Wisconsin Insect Fest on Friday, Aug. 1 in Madison. Because she believes wetland insects live a hell-raising lifestyle, she titled the talk: “Sex, Violence and Deception: The Hidden World of Wetland Insects.”

The audience can learn about wetland insects found in Wisconsin, including the burying beetle — which is one of the few beetle species to have a parental care system.

Marsh said the burying beetle takes dead rodents, dehairs them, then buries them in the ground to prevent other predators from stealing dinner. Then, the burying beetle will lay its eggs on top of the carcass, so once hatched the larvae can feast on it. It is like a family meal.

She also studies the Conopidae fly which parasitizes hornets. A specific fly in this group has a can opener shaped abdomen. The female pries open the hornet’s abdomen to lay an egg.

“When the egg hatches, the larva will start feeding on that hornet and kind of make it into a zombie. So it lays on the forest floor, and then as it grows it will eat (the hornet) until it’s completely gone,” she said.

Marsh said the wetland insects are under-researched, mainly because the conditions of the bogs and wetlands present challenges for researchers.

At times when she is out collecting insects, the mosquitos are so thick she can wave her hand through a swarm and create a trail. During the summer months, she wears protective gear head to toe and still gets so many mosquito bites she takes prescription medication to ease the itching at night so she can sleep.

Marsh hopes to help people better understand the value wetland insects bring to the ecosystem. Although their ecological niche might seem gross, without them the marshes and bogs would be covered in leaf litter.

“These are the good guys,” she said. “We need them.”