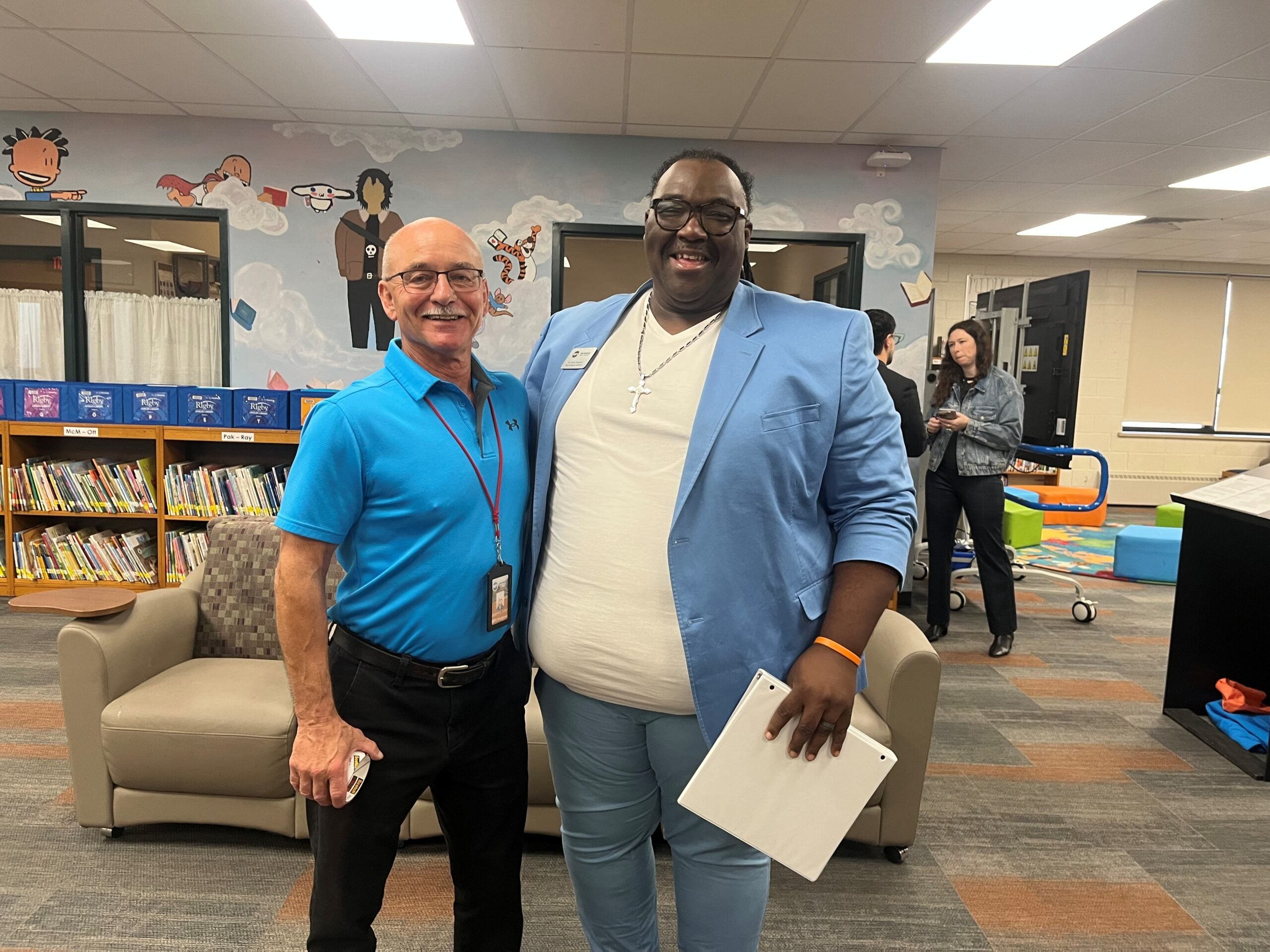

When Brad Sturmer became principal at Winskill Elementary School eight years ago, fewer than 40 percent of the students were proficient in math.

The school’s math scores mirrored the state and national average, but Sturmer, who spent 15 years teaching high school math, knew that wasn’t acceptable.

He saw students who hadn’t learned basic math skills by third grade struggle for the rest of their academic career.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“The problem is that it snowballs into: ‘Math is hard; I hate math,’” Sturmer said. “There is a subject in high school called Algebra 2 that a lot of colleges need you to be able to pass to get accepted. But Algebra 2 is really hard for kids that don’t like math and struggle with it.”

Sturmer brought in math coaches for the teachers at the Grant County school, and he moved around the staff.

Fifth grade math teacher Missy Sperle compared Sturmer to a skilled baseball manager who knew how to change the roster so the team could succeed.

Now, nearly 80 percent of the students at Winskill are either advanced or meeting expectations in math, according to the latest Department of Public Instruction report card.

Sturmer said the students at Winskill are just like the students across Wisconsin. His school just has different systems in place.

The difference, Sturmer said, is that Winskill focused on teaching math — and made sure its teachers were using the latest evidence-based practices, not just teaching it the same way they learned when they were in school.

“It comes down to teaching the why behind mathematics and how things work,” he said. “Not just teaching tricks. That’s a big mistake people make.”

‘You have got to find time for math and the way you teach it’

For the last several years, the science of reading has gotten attention. In 2023, Gov. Tony Evers signed into law a set of sweeping changes to how children in Wisconsin are taught to read.

Math champions like Sturmer and Sperle celebrate the state’s efforts to improve reading scores.

But they say math should not be left behind.

Sturmer said many people become teachers because they love children and education, but they are not taught how to teach math — so they avoid it.

“You have got to have the time for math and the way you teach it,” Sturmer said. “I think people underestimate the importance of that academic foundation.”

On the latest National Assessment of Educational Progress test, sometimes called the “Nation’s Report Card,” 42 percent of Wisconsin’s fourth graders and 37 percent of the state’s eighth graders tested “proficient” in math.

Nationally, 39 percent of fourth-grade students and 28 percent of eighth-grade students performed at or above NAEP proficient.

Addressing ‘math anxiety’ in students — and teachers

Winskill Elementary School is in Lancaster, the 4,000-person county seat of rural Grant County in southwestern Wisconsin.

The school has about 450 students, about 40 percent of whom are economically disadvantaged. That’s similar to the average across the state.

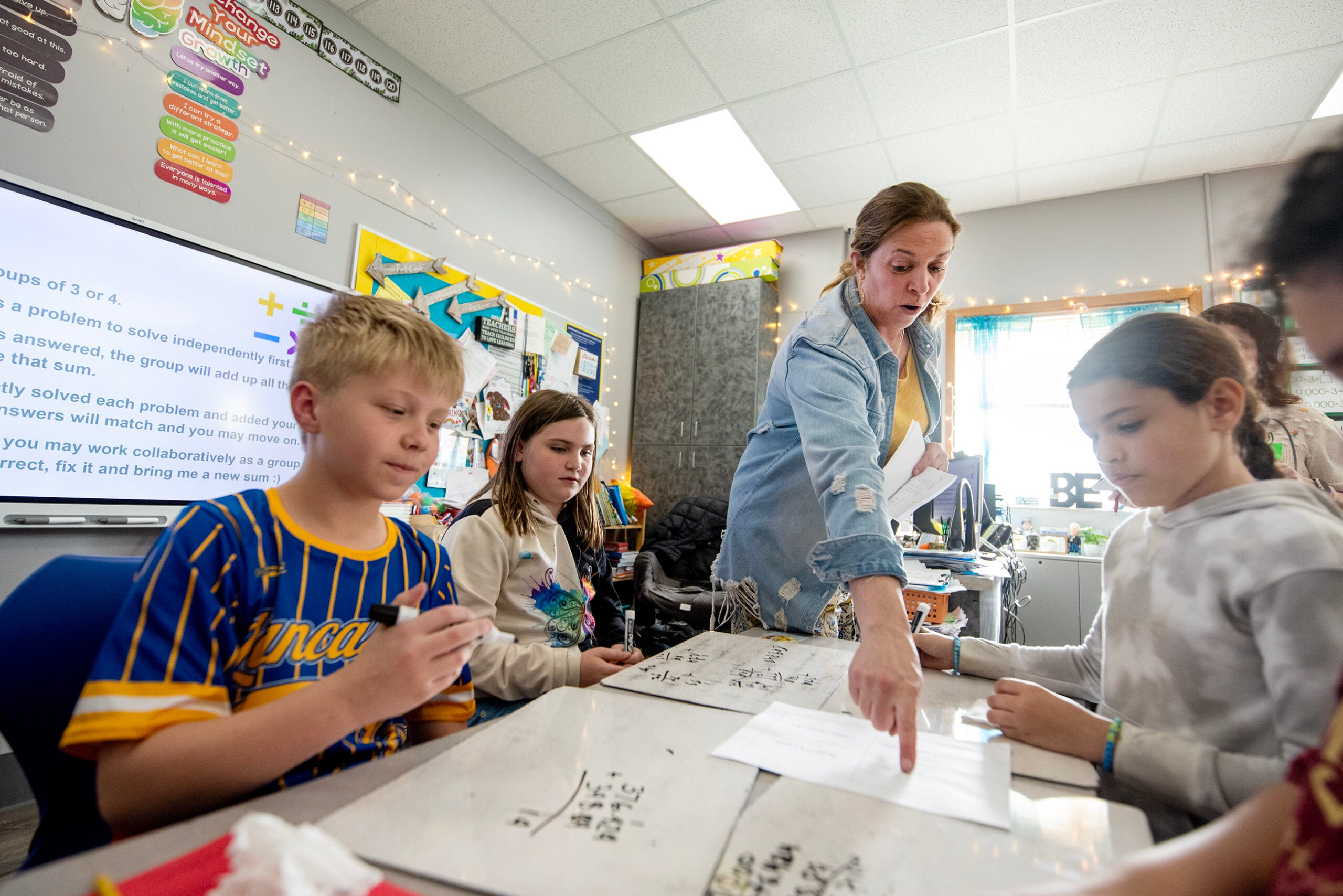

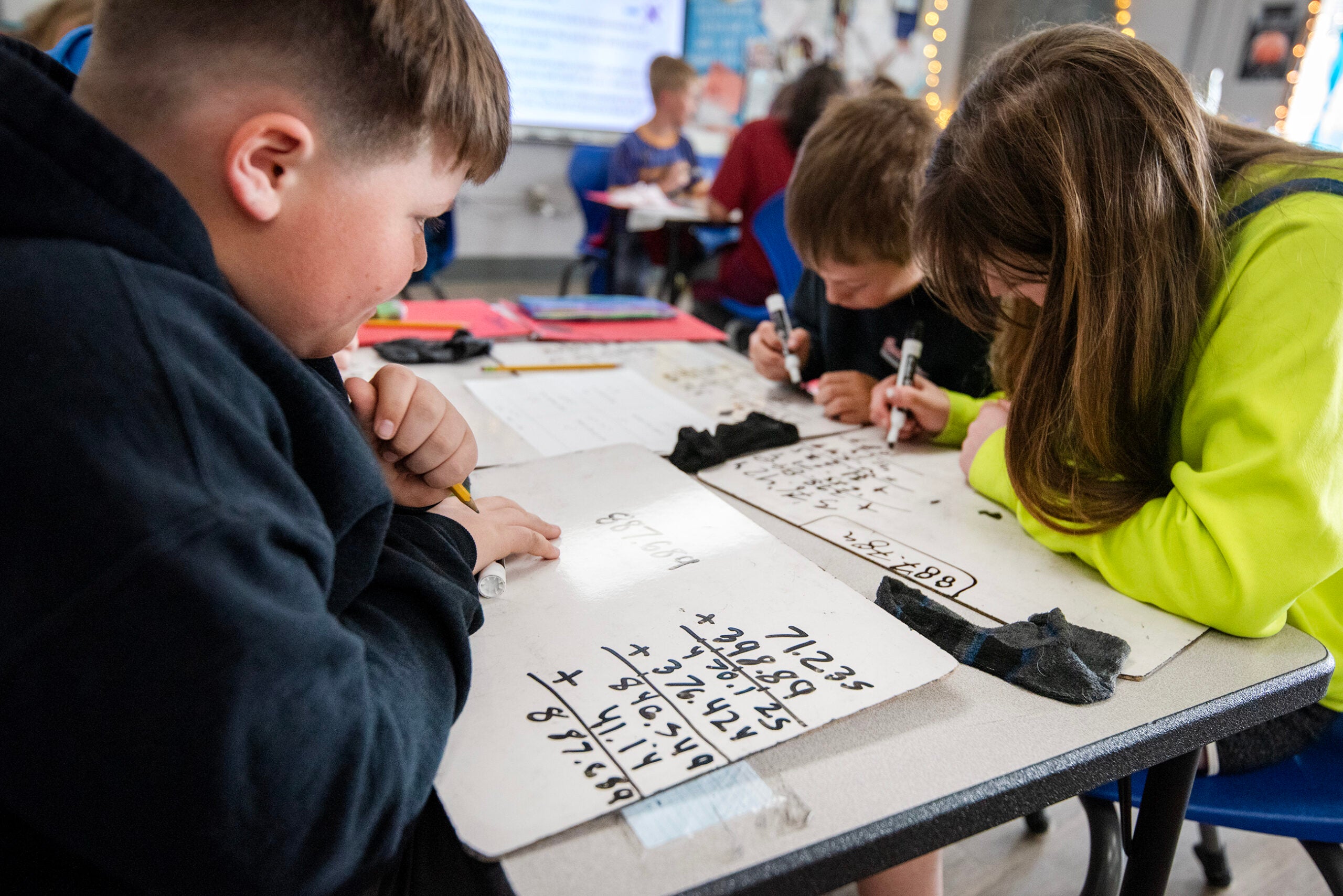

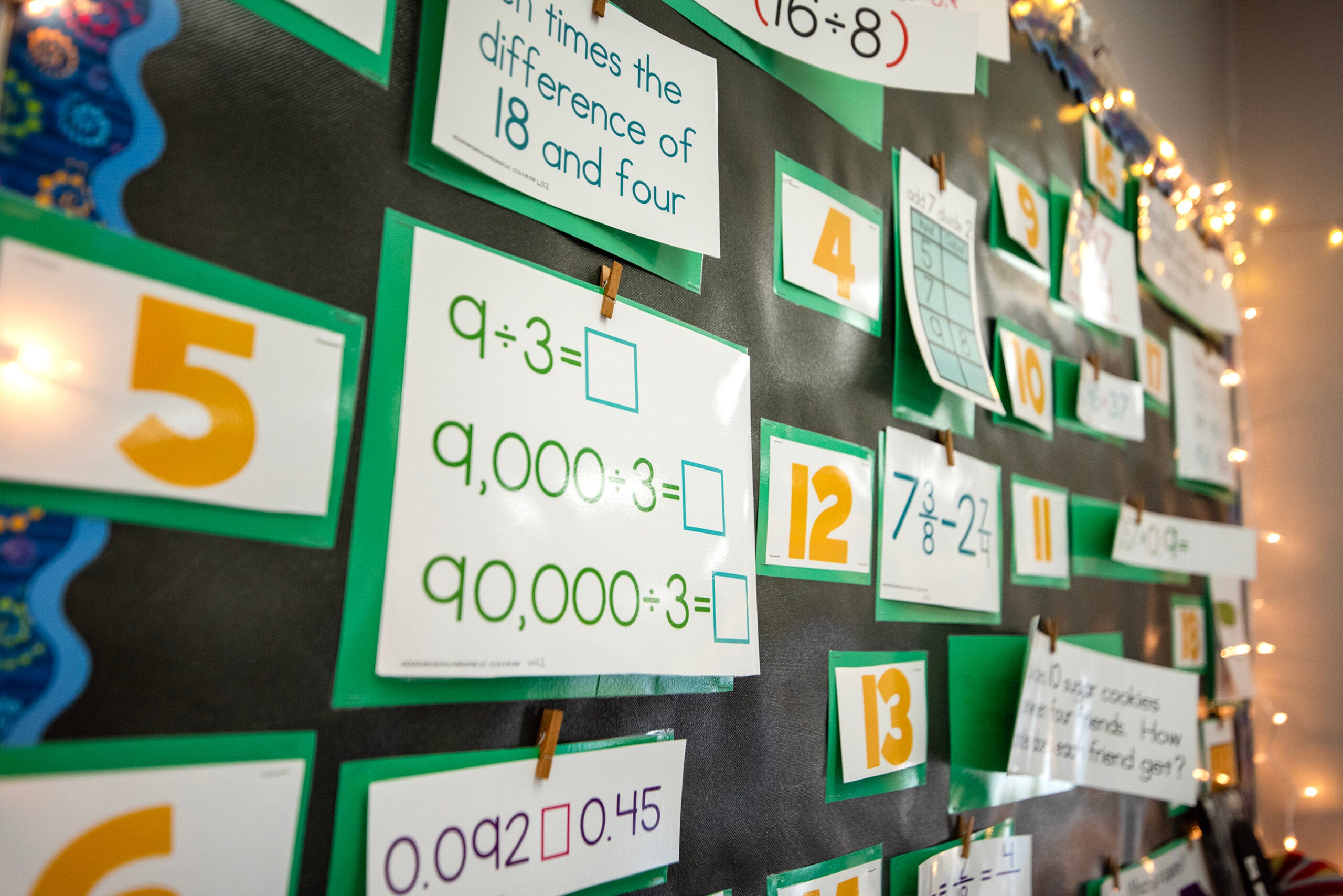

Under Sturmer’s leadership, the days of sitting in rows and working on math worksheets are gone at Winskill. The school has completely reimagined how math is taught, incorporating group work, letting students stand and avoiding the math “tricks” that Sturmer said actually hinder learning.

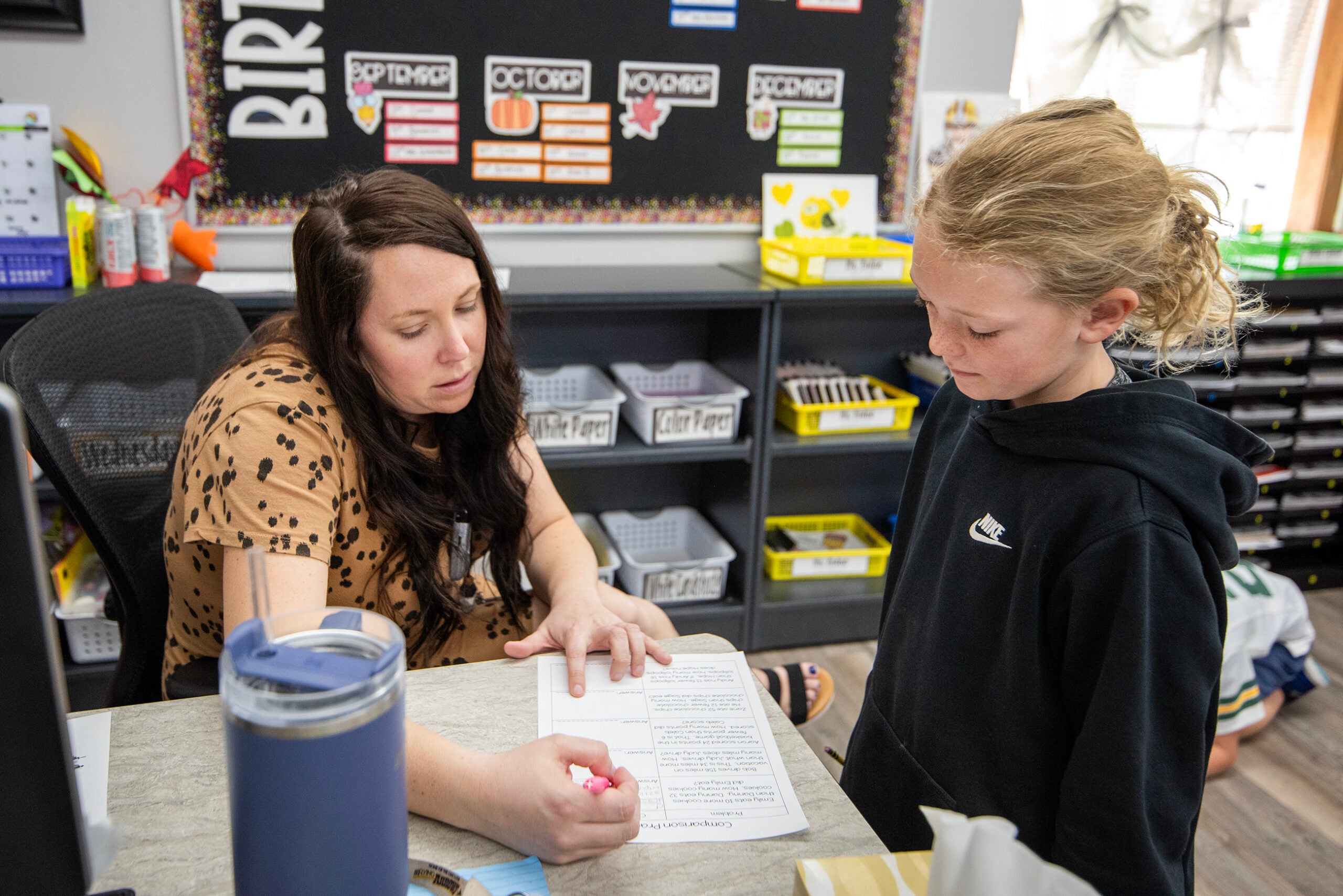

When Sturmer arrived at Winskill, he decided that instead of having elementary teachers cover all the major academic subjects, third- through fifth-grade teachers would be assigned to teach one subject. At that time, he moved Sperle from second grade to fifth grade math.

She panicked, but she trusted Sturmer.

Then she spent the summer learning how to teach math.

“We had some professional development, and that helped a lot,” Sperle said. “And then I started learning more. I started realizing there’s a better way of doing things. We need to change what we’re doing to meet our kids where they’re at.”

Now, Sperle is a master at her craft. She was one of six Wisconsin finalists for the 2024 Presidential Awards for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching.

The award is considered the highest honor bestowed by the U.S. government for math and science teachers.

Heather Peske, president of the National Council on Teacher Quality, said research shows teachers who have content knowledge and an understanding of the best instructional methods to teach math have the best outcomes.

“Elementary math teachers describe sometimes struggling to teach math and described feeling some math anxiety,” Peske said. “Having a school district, like the one in Lancaster that is focused on teachers’ content knowledge and additional training, will sustain effective math instruction.”

Group work, letting students stand can improve math learning

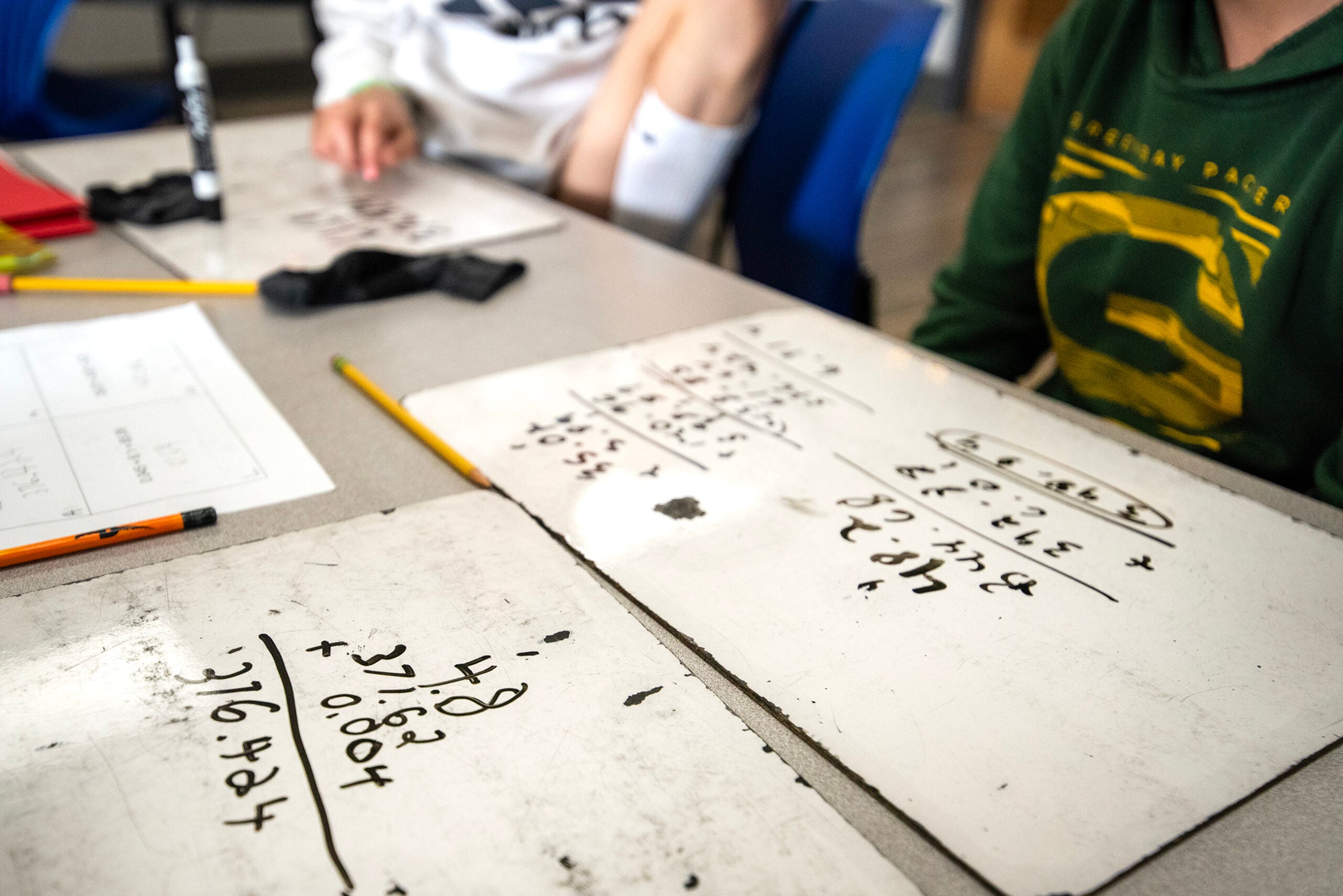

On a school day in April, the students in Sperle’s class worked in small groups at large whiteboards around the room.

Sperle starts every math class with a group problem that lasts about 20 minutes before getting into the day’s lesson.

She said there’s a lot of research showing when students start their math class standing and working together on a problem, they are more engaged.

At the whiteboards, the students work together on a problem to figure out which one of the school’s math teachers went over their budget on a hypothetical shopping trip.

Each group uses a different method to figure out the problem.

Sperle floats from group to group giving guidance.

Winskill math teachers meet weekly to make sure they’re on the same page and that students will move seamlessly to the next grade level.

For example, the children in Maria Kamps’ kindergarten class started the day with “True/False Tuesday.”

The 5-year-olds could see and feel the math in the softly lit classroom, where Cookie Monster explained the lesson before Kamps sat on a checkerboard rug and used sticks and songs to illustrate six minus five.

“I’m going to match, match, match them up,” she sang sweetly, moving the sticks around.

Upstairs, students in Karly Enloe’s third-grade class also kicked off the day with True/False Tuesday, but at a faster pace using a smart board and small groups.

Enloe challenged the students to “be confident” and shout out their answers as soon as they knew them.

Sturmer said the changes he and the staff made at Winskill were substantial, but not difficult.

“You’ve got to have strong people in place, and I recognize that not all schools are fortunate enough to have the strength that we do,” Sturmer said. “But there are a lot of schools that have a ton of great people in place. Then it just comes down to your structures and systems and how you teach mathematics.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.