The debut poetry collection by Madison’s poet laureate Steven Espada Dawson, called “Late to the Search Party,” explores how addiction, cancer and loss have touched his life.

Espada Dawson told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” that he uses poetry to help process both painful and joyful events in his life.

“I am trying to write within the shadow of these things to understand where I’m at, both in this world and also in my today,” Espada Dawson said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Espada Dawson shared that he’s most proud of the work he does with incarcerated people and students who are impacted by the justice system.

“I’ve done workshops with these students already,” Espada Dawson said. “We are going to have a radio reading for incarcerated poets. It’s a little proof that they are heard — that something they made is not just art that dies within these little walls, but can echo far outside of the prison.”

On “Wisconsin Today,” Espada Dawson shared the inspiration behind his poetry and his journey from writing in Los Angeles to being Madison’s poet laureate.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: Do you have to give yourself permission to write really deep personal things about your life, like your brother going missing, his addiction and your mother going through cancer?

Steven Espada Dawson: I have always written to understand how I’m feeling. When you’re living with people who are going through complicated things — for example, addiction, which is a large theme of my collection — the shadow of addiction is almost always larger than the individual.

KAK: Has poetry put you in a better place?

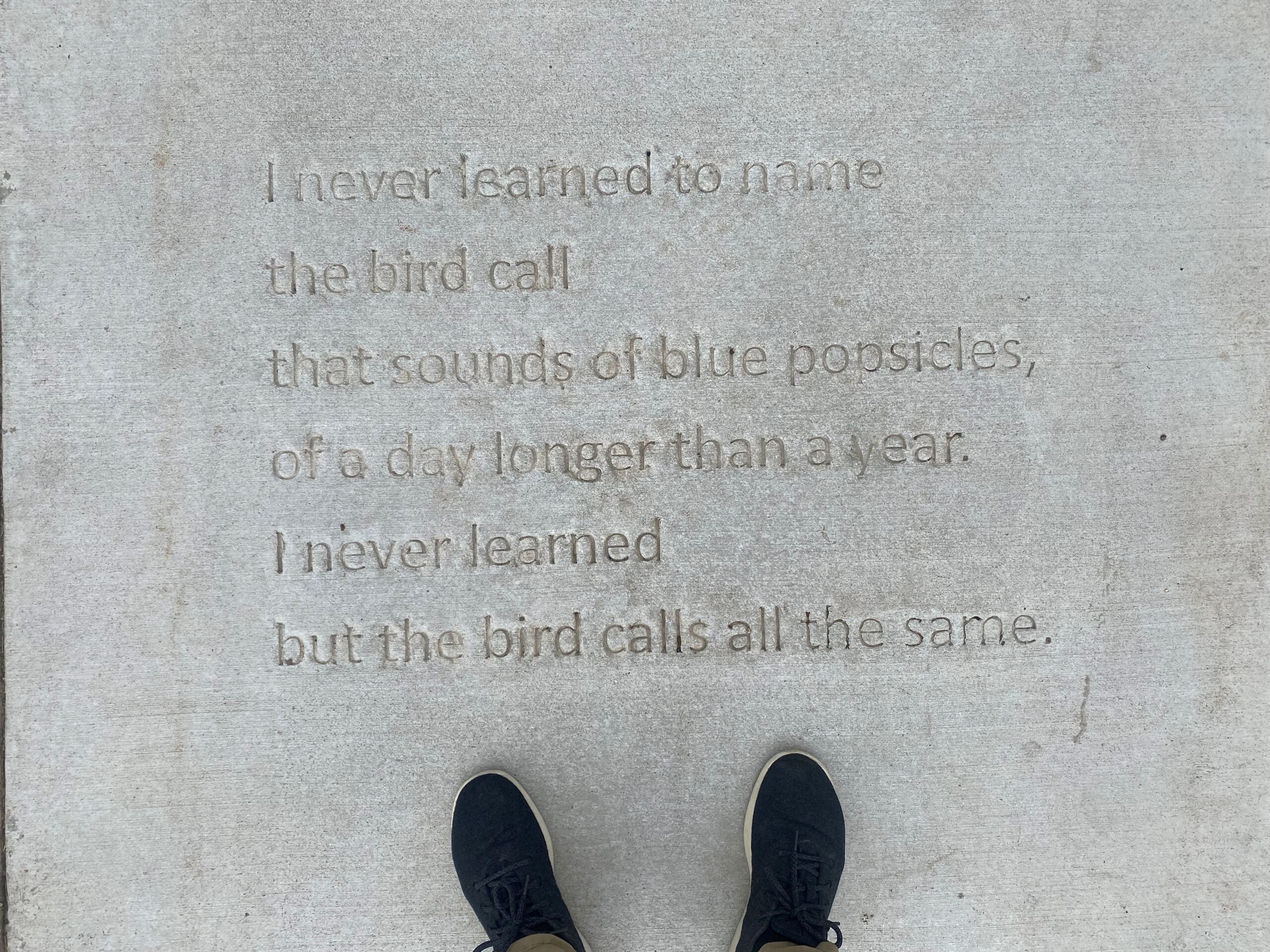

SED: Yes, absolutely. I think for me, it was approachable because it’s a small thing. So many poems that have changed my entire life, I have been able to read in 45 seconds. There aren’t many other art forms that do that. I think what we might sometimes refer to as a “small economy of language” really challenges you, both as a writer and as a reader.

And I definitely wouldn’t be where I am today — as far as my mental health journey and learning how to live in this world — without poetry. I can say that 100 percent. It has been really helpful, and I’m in a lucky position to be able to teach people how to write poetry, and, more importantly, how to read poetry. I can say that it’s helped many of them, too.

KAK: I want to touch on the heart. A number of your poems and their titles reference the four chambers of the heart. The book is organized into four sections. Why does this organ lend itself to your poetry?

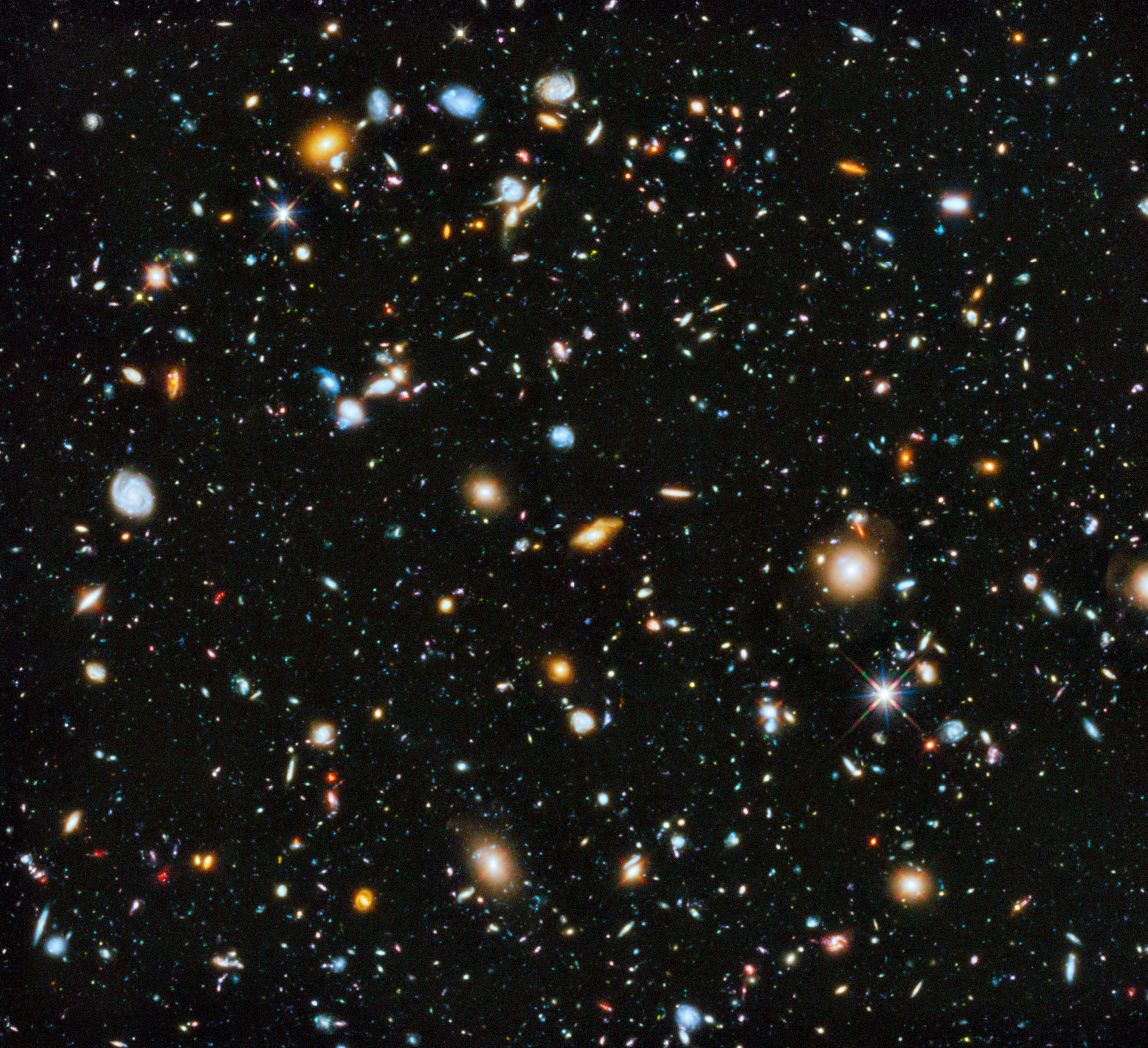

SED: Whenever you write about the heart, or whenever you write about the moon, you’re tapping on this microphone that feels ancient. And I’ve always really loved that challenge. There have been poems about the moon since there have been poems, right? You go into this thing knowing that thousands of people have tried to write the same poem that you just wrote. How do you make it new? I feel that same way about the heart.

I’m really fascinated with trying to make things new that are not new. I’m sort of borrowing the voice of an old poetry professor here, but he would always say, “How do you make the stone stony again?” This thing that has been articulated in so many ways throughout the years, how do you make it matter again? I’ve always been up for a good challenge.

As you said, my collection is in four parts, and that echoes the four chambers of the heart in poetry. Also, four-line quatrains tend to be the slowest stanzas because they’re so uniform. They don’t have the same momentum or propulsion as triplets. So when writing about death and when writing through elegies, I’m also thinking, “How do I slow things down?”

KAK: You’re originally from Los Angeles. Many of your poems have these LA references, but you also have one about Madison’s Lake Mendota after sunset. Why did you choose this spot in Madison to write about?

SED: I am a city boy through and through. Nature terrifies me. In Madison, when you’re on the isthmus, you don’t necessarily see that lake, that has just been this feature of your life the whole time you’ve lived here, as nature. It is this prominent, intimidating thing for me.

I’m lucky to be just a couple blocks from the lake, and sometimes I will go out there, when the weather permits, and just sit with it. It is just this big black pit of a thing, and you can’t help but to feel magnetized to it. So it does feel like, when I’m alone with the lake, we’re having a little conversation. … It’s become a very new, profound symbol for me living here, and I am always writing with my environment in mind.

KAK: Do you have any words of advice for aspiring writers and poets who can relate to some of these images, who can relate to your story?

SED: If it’s safe for you — and I think that you have to decide what that means — write towards either your discomfort or write towards your joy. I think whatever art you do, move towards discomfort to learn more about yourself; or move towards joy to learn about what is possible for you. I think that will save your life. It did me.