Katie Hudnall thinks wood is magical.

“The experience of working subtractively in wood to carve or to shape the material is just incredibly satisfying,” she told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “It is the most satisfying feeling in the world to just take shavings off of a board.”

It’s about the carve, the slow movement and the machines. During a project, she said her brain tunes out, leaving her hands and eyes alone to communicate. She calls it the “language of woodworking.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

As a child, Hudnall said she struggled as a student, with bad grades and a difficulty learning to read. But she was always an excellent artist. So when she moved to Wisconsin as a tenured professor to lead the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s artistic woodworking program, it was a pleasant surprise.

“Who thought I’d be the professor in my family?” she said at her studio at the Arts Loft.

As an artist, Hudnall’s work is featured around the country, most recently at the Museum for Art in Wood in Philadelphia.

She’s been running the woodworking program at UW-Madison since 2020.It is one of few art programs in the country dedicated to wood, combining the engineering and technical skills of carving and building with artistic creativity.

Hudnall uses reclaimed wood she often finds in dumpsters to create objects. Her pieces are funcional and can be recognized as maybe a cabinet or table. But there is always something unexpected about their form.

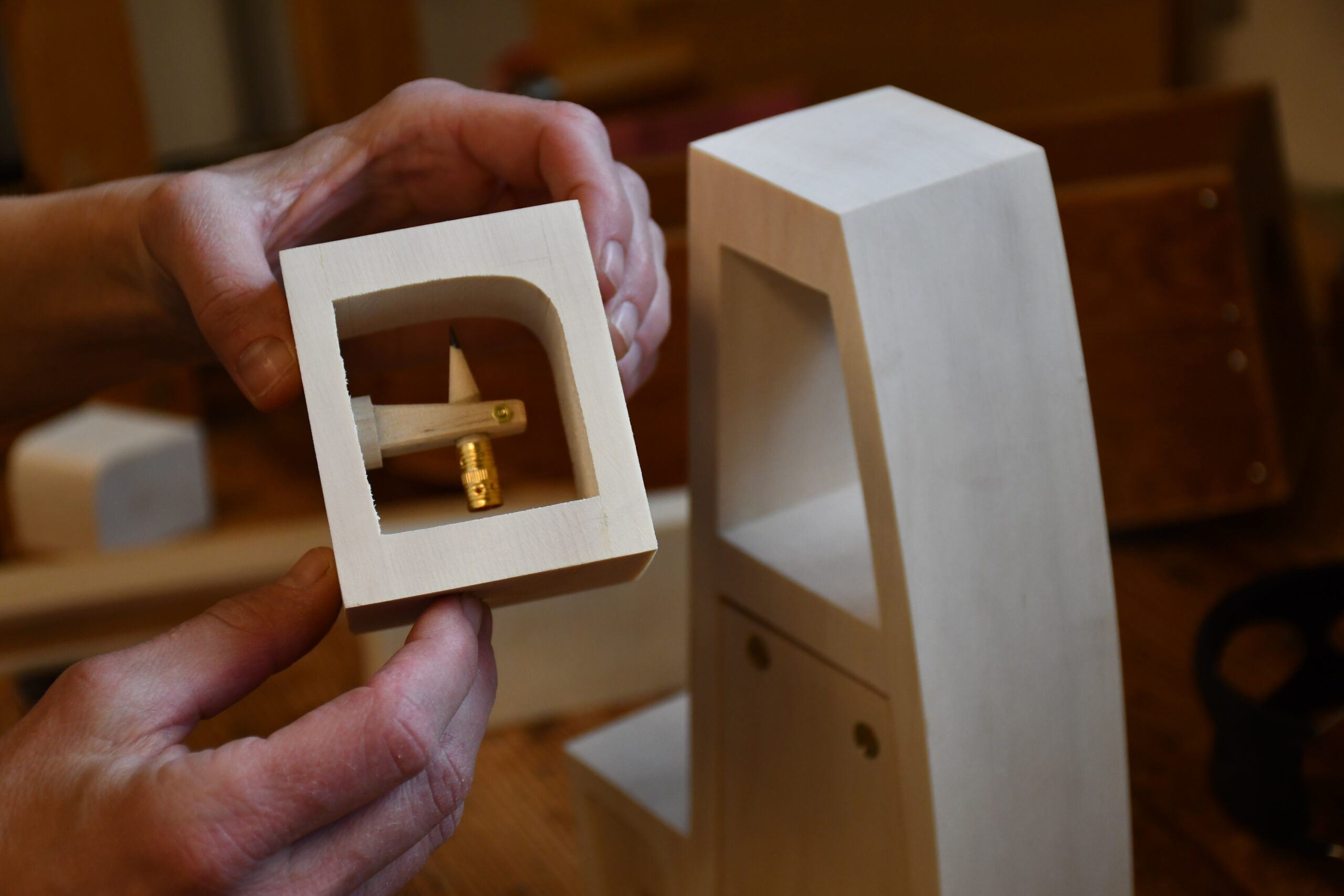

Some of Hudnall’s recent work includes a chessboard where the pieces are creatures that live in the cavity, and a cabinet with mini coffins for her dead pencils — because the pencils have drawn so many lines for her, they deserve a final resting spot, she said.

Wood feels like part of the family

Hudnall thinks of wood as a medium that we all have an intimate relationship with but know little about.

“Wood tends to come in our domestic spaces, in our comfortable private spaces. It’s the floors and the ceilings and the furniture and the objects that we sort of work with on a daily basis,” Hudnall said. “One of the things I think is magical about it is that we as human beings have this relationship with it. It feels like a member of the family.”

When working with wood, students and artists have to pay attention to the grain, the knots and the direction. It isn’t like clay that is homogenous and can be molded; you have to listen to it, Hudnall said.

Each board is unique and certain species of wood have different properties. When Hudnall is working with beginner students, they often use poplar because it’ i’s a fast-growing, domestic lumber and is relatively easy to carve compared to some of the harder woods, like cherry or maple.

Students marry art and function

As students make their way through the program, they gain insights into wood as a versatile art material.

They start the semester learning the anatomy of a log and all about trees, down to the cellular level. This helps students understand the colors and shades of the wood they are working with, but also undertand why it cuts and shapes a certain way.

Then Hudnall assigns the first project: Not a spoon.

“A very traditional carving project in woodworking is a spoon. It’s got a concave. You use one set of tools for that. It’s got a handle form. You use a different set of tools for that,” she said. “With the ‘not a spoon’ project, I want them to be able to do both of those things, but I also want them to bring in their artistic practice.”

One student’s result: a foot-long toothbrush with the dollop of toothpaste acting as the bowl of the spoon. Other students created animals like a Brachiosaurus with a hollowed out head or a whale where the blowhole is turned into the possible spot for soup.

Although Hudnall’s students come from multiple disciplines and not all of them will become professional woodworking artists, she intends for the technical skills she teaches to help them later in life.

“We have dentistry students who come in and learn how to carve, which I know is going to help them carve somebody’s teeth someday,” Hudnall said with a laugh.

She also hopes she can pass on the joy of carving wood, bit by bit. She said it’s a slow process and something she finds peace in.

“It’s sort of this connection that kind of bypasses my brain and is really just like this conversation between my hands and my eyes.” Hudnall said. “And I think that that’s a really wonderful space to be in and one that we just don’t let ourselves be in very much anymore.”