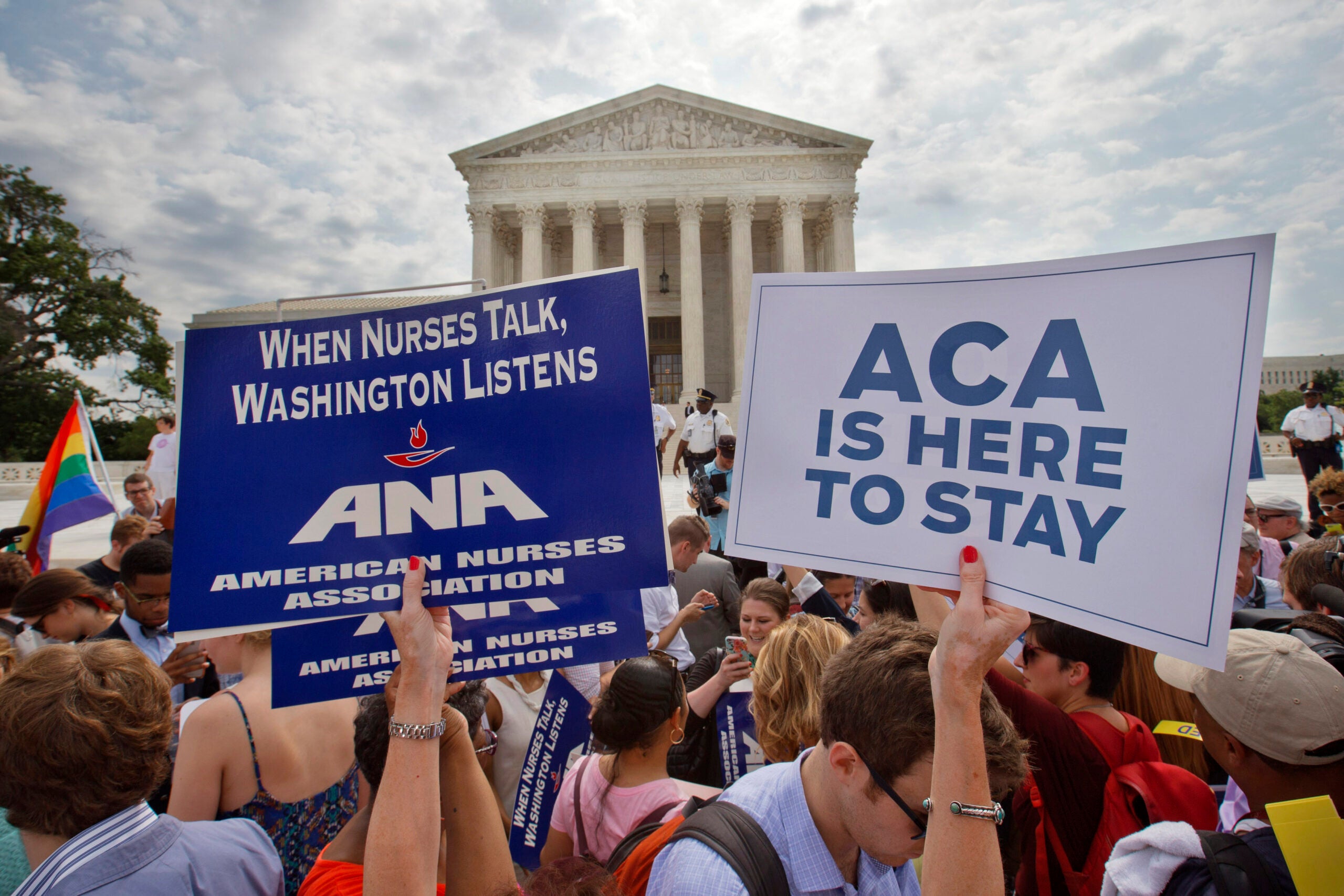

Expanded health insurance tax credits passed in 2021 for the Affordable Care Act are set to expire at the end of the year.

Without them, health insurance premiums for Wisconsin families are projected to spike by hundreds of dollars per month, leaving some unable to afford coverage.

Congressional Democrats are pushing for these tax credits to be extended and are holding up negotiations over a stopgap federal funding bill as leverage, with a potential government shutdown approaching Wednesday.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

KFF Health News’ Chief Washington Correspondent Julie Rovner said the impacts of these tax credits spread beyond just those who rely on the ACA marketplace for health insurance.

She joined WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” to discuss what role this money plays in the health care system and how leaders on both sides of the aisle are responding.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: What do these tax credits from the Affordable Care Act do? Who benefits from them?

Julie Rovner: So under the Affordable Care Act, as it originally passed, the tax credits help people with mostly lower incomes, up to 400 percent of the poverty line. That’s about $100,000 for a family of two to afford their insurance. It offsets some of the cost of the premiums for lower income people under 150 percent of poverty. It also offsets some of their out-of-pocket costs.

In 2021 during COVID, Congress expanded the subsidies pretty dramatically. They basically made health insurance premiums free for people under 150 percent of poverty and expanded them up the income scale so that people over 400 percent of poverty wouldn’t have to pay more than 8.5 percent of their income toward their premiums.

KAK: If the tax credits are allowed to expire at the end of the year, what are some of the consequences? Who will be affected?

JR: Well, even the insurers have estimated that they’ll have to raise premiums because so many people will no longer be able to afford their coverage that they’ll drop coverage altogether. They estimate that healthy people are the ones who are most likely to drop that coverage because they can’t afford it, and they don’t need it.

The sicker people who desperately need it may try to hang on to the coverage, even if it’s more expensive. So that’s one of the things that will increase premiums. We’re seeing an increase in medical costs, in part due to tariffs and due to other policy changes. So there’s really a concern that many people will lose their health insurance if these expanded premium credits expire.

KAK: How might this affect employer-sponsored health care premiums?

JR: There’s a concern that if people no longer have insurance, they’re going to end up in the emergency room when they’re sick. That cost is going to have to be passed along to someone. Among others, it gets passed along to people with employer-provided insurance and other types of private insurance. It basically increases health costs for everyone. So even if you’re not immediately affected by this, you’re affected by this as long as you have health insurance.

KAK: What is the opposition to this from congressional Republicans?

JR: The big budget bill that Congress passed in June made a lot of changes to the Affordable Care Act. It was not advertised as “Let’s repeal the ACA,” which they tried and failed to do in 2017, but they did a lot of things that are going to make it harder for people to get coverage, harder for people to continue their coverage, and fewer people are now going to be eligible for subsidized coverage.

There are still a lot of Republicans that would like to see the Affordable Care Act, if not go away entirely, work a lot less well than it works now. On the other hand, there are also a lot of Republicans who realize that their own constituents are about to see these eye-popping increases in their premiums, and they’re not going to be happy about it — particularly in some of these redder states that didn’t expand Medicaid.

People between 100 and 138 percent of poverty have not been eligible for anything except these tax credits. If they go away, those people are going to be unhappy. So there’s a lot of Republicans who have a lot of disquiet about letting these tax credits expire. There’s a division within the Republican Party about whether or not to continue them.

KAK: Do you think that Democrats will be willing to let the government shut down over this issue? What are you hearing?

JR: It certainly looks that way. We’re in very unprecedented times. Normally, if there was what we call a “clean CR” (continuing resolution) like, “Let’s just extend funding for seven weeks while we continue to negotiate,” that would usually be OK with both sides. But the Republicans this year, this Trump administration, has been cutting funding unilaterally, which is being fought about in the courts. The Democrats are afraid of cutting a deal that the Republicans and the Trump administration won’t keep. Nobody quite knows what’s going to happen.