Farm groups are disappointed with Gov. Tony Evers’ veto of a bill that would largely prevent local regulation of animal welfare on farms, but its opponents say it’s a win for local control.

State Sen. Romaine Quinn, R-Cameron, and Rep. Treig Pronschinske, R-Mondovi, introduced the legislation. The bill cleared the Republican-controlled Legislature last month.

The proposal would have barred local governments from enacting certain local regulations of animal facilities in areas primarily used for farming unless there’s a substantial threat to public health or safety. It received support from more than a dozen agricultural and veterinary groups, but animal welfare and environmental groups opposed the bill.

“I object to removing control over animal welfare standards from local authorities and preempting their ability to pass ordinances with the interests of their community in mind,” Evers wrote in his veto message on March 29.

The governor said the bill could have potentially revoked ordinances that have already passed with community support. He also said he objected to its effects on deterring “enforceable” regulation of animal welfare.

Supporters say local officials don’t have expertise on animal welfare

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The proposal came as states like California have required more space for some animals in response to voters concerns about animal treatment and living conditions. Quinn said such policies can infringe on farms’ right to conduct business. He said many smaller communities don’t have the technical expertise to define such standards, adding Wisconsin farmers should be held to the same statewide regulations.

“Our farmers’ margins are super tight, and I think anytime we enact local ordinances that go above and beyond what we all expect, just hurts their ability to conduct business,” Quinn said.

Under the bill, local governments wouldn’t have been able to require animal welfare standards that are more stringent than state law. The proposal would have limited local regulations that require or bar medications and vaccinations, and it would have prevented local limits on the species of animals or how they’re used at facilities.

Brad Olson, president of the Wisconsin Farm Bureau Federation, said in a statement that local governments shouldn’t override the judgment of farmers and veterinarians on animal welfare. Olson, who is also a Polk County supervisor, said the bill aimed to prevent “anti-farming activists” from enacting local ordinances that they say are harmful to farms.

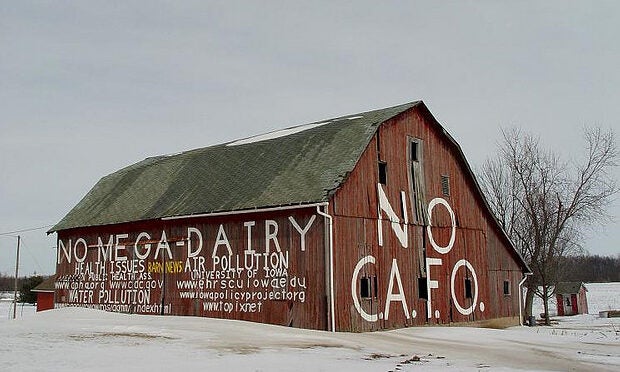

In northern Wisconsin, half a dozen towns in Polk and Burnett counties developed operations ordinances for large farms known as concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs.

Bill in response to local ordinances regulating farms

Communities like Laketown sought to regulate pollution, odor and animal welfare in response to plans by Cumberland LLC to build a farm for up to roughly 26,000 pigs nearby. Lisa Doerr, a hay farmer in Laketown, said the ordinances ask large farms to submit plans to address local concerns in those areas. She said she’s thrilled Evers vetoed the bill.

“We have a right to protect ourselves or our town officials have a responsibility to protect themselves and the people that live in their towns,” Doerr said.

In 2022, residents represented by Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce, or WMC, sued Laketown over its CAFO ordinance. New leaders in the community ultimately rescinded the ordinance. Tim Fiocchi, senior government relations director with the Farm Bureau, said they’ve seen ordinances that would create a requirement for farms to operate 40 hours a week.

“That’s simply unrealistic. You can’t operate a farm 40 hours a week, and so that would pretty much shut you down if that was what gets passed,” Fiocchi said. “The ordinances that are specifically addressed by the bill are slightly different, but it leads to the same type of concern.”

An ordinance for the town of Trade Lake, where the hog farm would be located, restricts use of tractors and other vehicles moving in and out of a CAFO facility between the hours of 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. on weekdays. It was later amended to allow for farming activities like haying, planting and harvesting after hours.

The town of Eureka is among other communities who have faced the threat of a legal challenge over its CAFO ordinance. The WMC Litigation Center filed a notice of claim, which typically comes before a lawsuit, on behalf of residents in October last year. Without Evers’ veto, Town Chair Don Anderson said they would’ve lost local control over CAFOs, which have drawn concern from community members over their environmental and health effects.

“We think our ordinance is fair and protects the town from these things,” Anderson said. “We have an attorney on hand if we should have a lawsuit against us.”

Fiocchi said the intent behind ordinances that are sometimes pursued, including in the name of animal welfare, is to prevent farms in those areas. Advocates for local regulation dispute that. Doerr highlighted two of the bill’s backers, Wisconsin Dairy Alliance and Venture Dairy Cooperative, are challenging state requirements for CAFOs to obtain permits that are intended to protect water.

Animal welfare groups like the Humane Society of United States expressed concerns that the bill’s broad scope would shield bad actors like puppy mills from oversight, but Quinn disputed that.

Quinn and Fiocchi said it’s possible that a similar bill will brought back in the next legislative session.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.