A federal judge in Baltimore recently ruled that DOGE, the Department of Government Efficiency, couldn’t have access to Social Security Administration data and would have to purge all non-anonymized data they had accessed prior to the ruling.

And an appeals court, also in Baltimore, allowed DOGE to have access to sensitive data from the Treasury Department, the Education Department and the Office of Personnel Management.

This access goes against long-established protocols for who can access this kind of data. And DOGE data access could open the door for bad actors, with potentially devastating consequences for the public.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

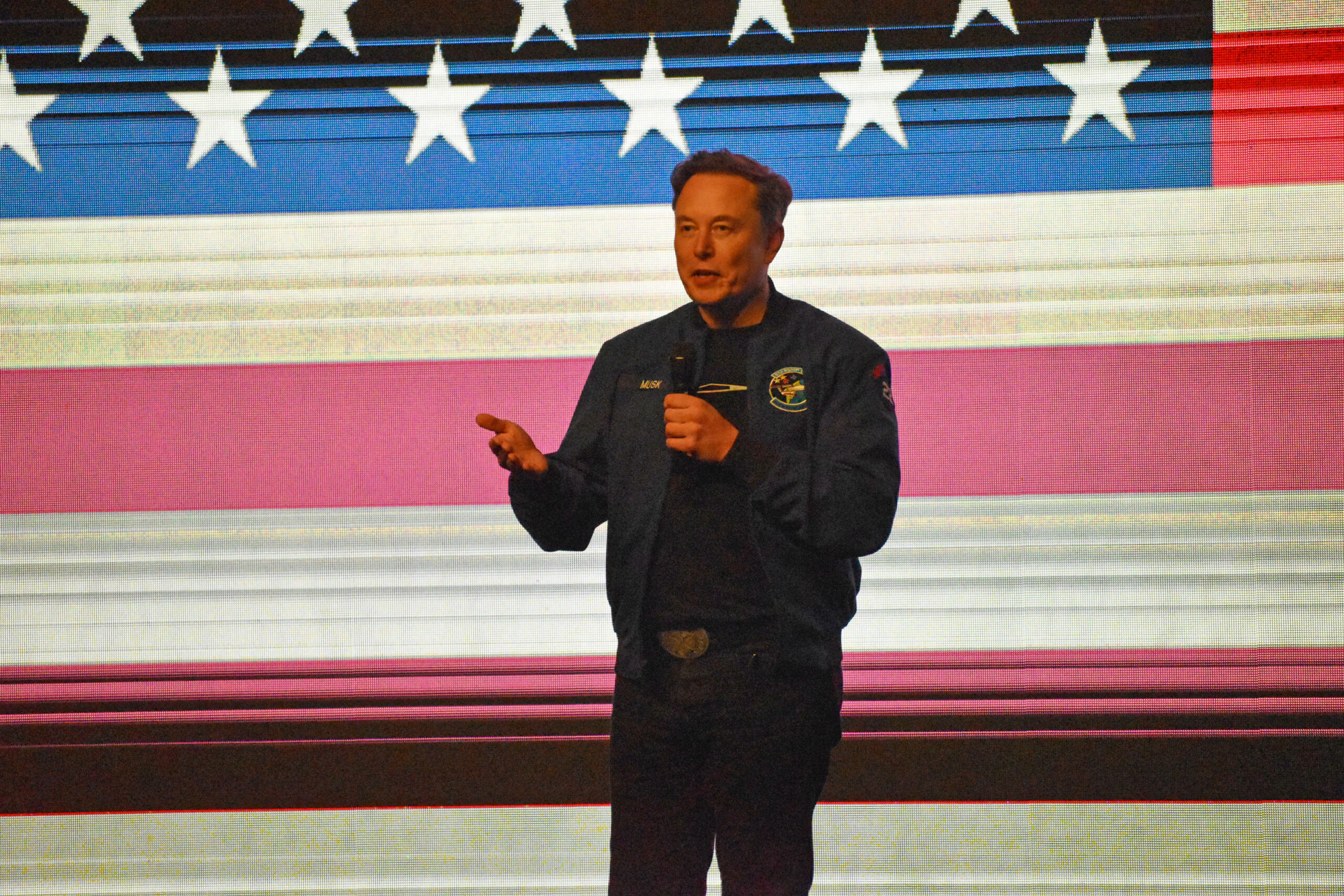

That’s according to Chad Johnson, an assistant professor of computing and new media technologies, and principal faculty member of undergraduate and graduate cybersecurity programs at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. He’s also director of the digital forensics lab at UW-Stevens Point.

Johnson recently spoke with WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” about the significance of DOGE access to government data.

The following has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Rob Ferrett: We keep getting this drumbeat of information about what kind of things DOGE is accessing. Based on what you’re able to see, how much of a concern is this for you?

Chad Johnson: From my perspective as an outsider looking in and with my industry experience, I’m not seeing signs of a lot of best practices being followed.

It seems like a lot of what is actually being done is not being shared with the public. What we’re seeing are the purported results of the efficiency-finding measures, but nothing on the actual process itself.

RF: Given all the data that the federal government has — all the data points that might be collected by the IRS, the Social Security Administration, the Department of Education, Small Business Administration, the list goes on and on — how bad would it be if that information were mishandled? Whether that’s a corporation that wants to use them for their own purposes, a government leader that wants to misuse them, or a foreign government. How big a treasure trove of information are we talking about here?

CJ: This question is difficult to answer because the last thing I want to do is contribute to any panic that may be out there. That said, I do think that concern is warranted.

The amount of information that we’re talking about here is unprecedented. The closest breach that I can [compare it to] would be the Equifax breach from 2017, and that was essentially a record on most adult American citizens.

What happened with Equifax was devastating, and we do believe that that was conducted by foreign actors that specifically wanted to get information about American citizens. If you consider things from an attacker perspective, why would they be interested in simple [personally identifiable information] on American citizens? That information isn’t useful in organized crime. It could possibly facilitate identity theft. But for the most part, we’re talking about nation-state espionage here. They want information on American citizens because it is useful to them in their national objectives. If the information that DOGE is accessing … were to be leaked or lost in any fashion, it would be devastating.

There’s a number of acts and FISMA [the Federal Information Security Modernization Act] and best practices that are implemented in order to protect [this information], and we have no indication that DOGE is following any of those at all. So they’re probably a lot softer targets now than they were before, all things considered. I would say there’s a significant danger here. In terms of our cybersecurity, the state actors that happen to be out there, I don’t think they’ve ever had it so good.

RF: An interesting thing about all this federal government data is a lot of systems don’t talk to each other. The Social Security Administration has their stuff. The IRS has their stuff, and they don’t share across agencies. The argument from DOGE is, “We’re going to bring these systems together. It’s going to help us efficiently catch fraud.” The counter argument is, “Hang on, that system is not a bug, it’s a feature. It’s a way to help protect our privacy. That’s something we want to do on purpose.” What do you make of those two different philosophies?

CJ: There’s an expression that I think we’re butting up against here called the “Chesterton Fence.” The idea is that a farmer buys a new plot of land, and as they’re surveying it, they see that in the middle of the field there’s this barbed wire fence. They look around and there’s nothing around, but they know that it would be just so much more efficient if they were to take the fence down. And then that way, they don’t need to travel around and go through the gate or work around the fence, essentially.

So they remove it, and then a couple of seasons later, they find out that the fence existed for a reason, and now they have a problem with cattle getting loose on their land. It’s a defensive strategy that is implemented, but the reason for it is no longer known. It’s tribal knowledge that’s gone, and somebody comes along and doesn’t recognize its purpose, but says, “Hey, this is inconvenient,” and so does away with it, and then finds out the hard way why it was implemented to begin with. I think that’s what we’re dealing with here.

Because the separation of these systems [exists to] protect our privacy and to make them secure. Typically, having all of your eggs in one basket is a bad defensive strategy to begin with, but it’s also designed to separate things out, to make things harder for attackers. They may infiltrate one system, and they’ll get some information, but they don’t have enough information from one attack to see the entire picture.

Efficiency at the cost of security, and therein lies the problem. They are mutually exclusive, unfortunately in this case, but one of those interests is foundational, and one of them is aspirational. We can’t have efficiency unless we are secure. We don’t have anything if we can’t maintain security. It’s the absolute most basic principle of a nation-state that we are able to protect our assets. So I don’t really see it as a trade off. It’s a sacrifice, if anything else.

I think that there are efficiencies to be made, and I think that there are ways to do it, but I see very little evidence that we’re going about it the right way.

RF: You mentioned you’re not telling people to panic right now, but people might look at this and be worried about their personal data and possible abuses of it. For folks who aren’t cybersecurity professionals, what are some of your general pieces of advice for them to be as secure as they can be?

CJ: Speaking just about what is happening with the federal government, the average person has very little influence over what is being done, very little ability to affect any kind of security. You can’t pull your information out of these systems. We don’t have a GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation] here in the United States. We don’t have an explicit right to privacy. We just have that which is implied by the Fourth Amendment. So in that regard, there’s very little you can do other than insist on those current rules being followed.

That said, there’s always things that one can do as an individual in order to, just in general, be more secure in terms of their cybersecurity posture. I mean, you’ve probably heard them a dozen times before. Things like not reusing passwords, using strong passwords, taking advantage of multi-factor authentication whenever possible, using all of the security measures that are available to you. Just in general, if you don’t put the information out there, it can’t be acquired later. So keep your own privacy in mind and take whatever steps you can to protect yourself.