As tick season returns to Wisconsin, the Marshfield Clinic Research Institute is once again calling on residents to take part in a statewide project that could lead to a better understanding of tick-borne diseases — and help prevent them in the future.

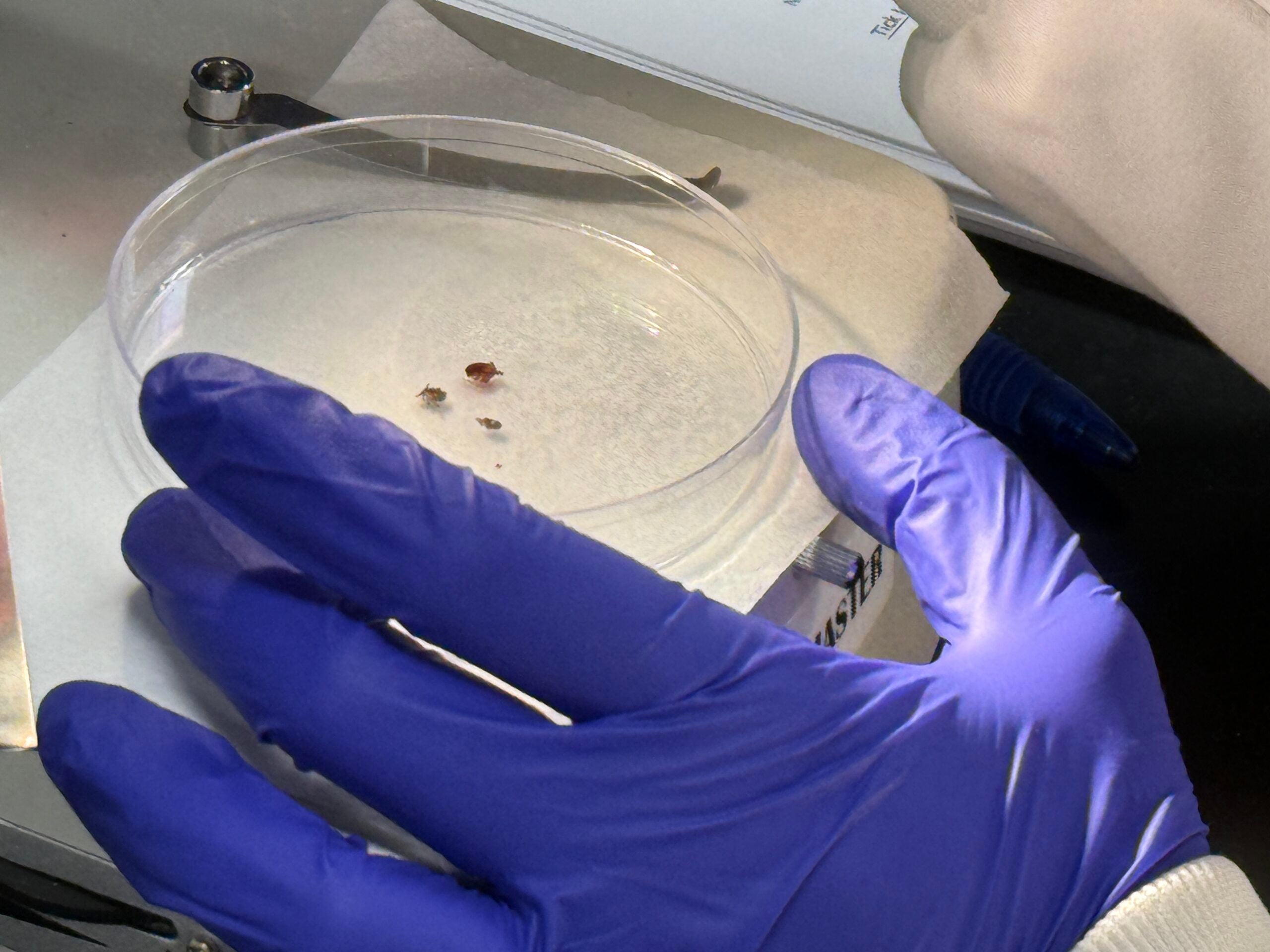

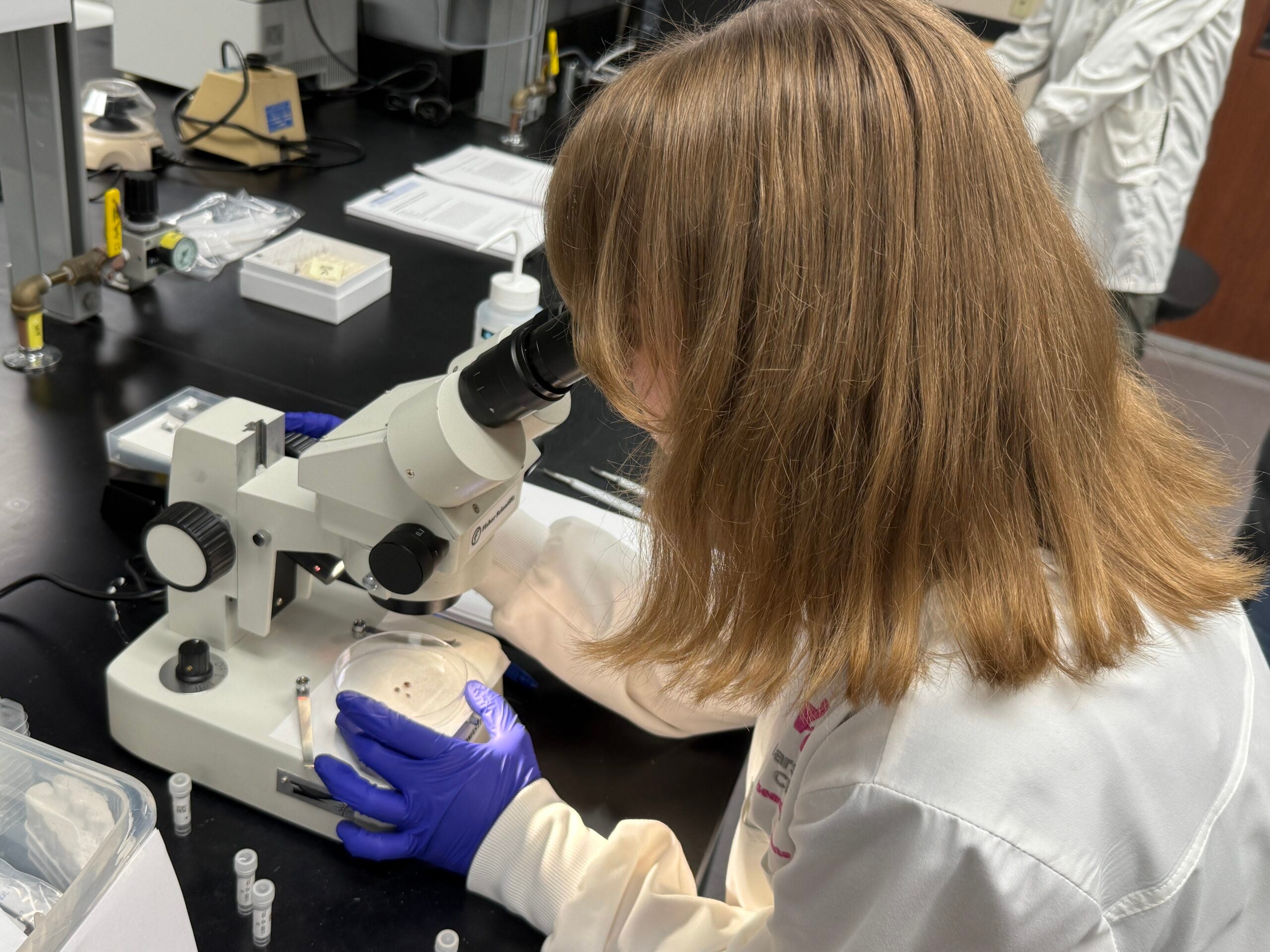

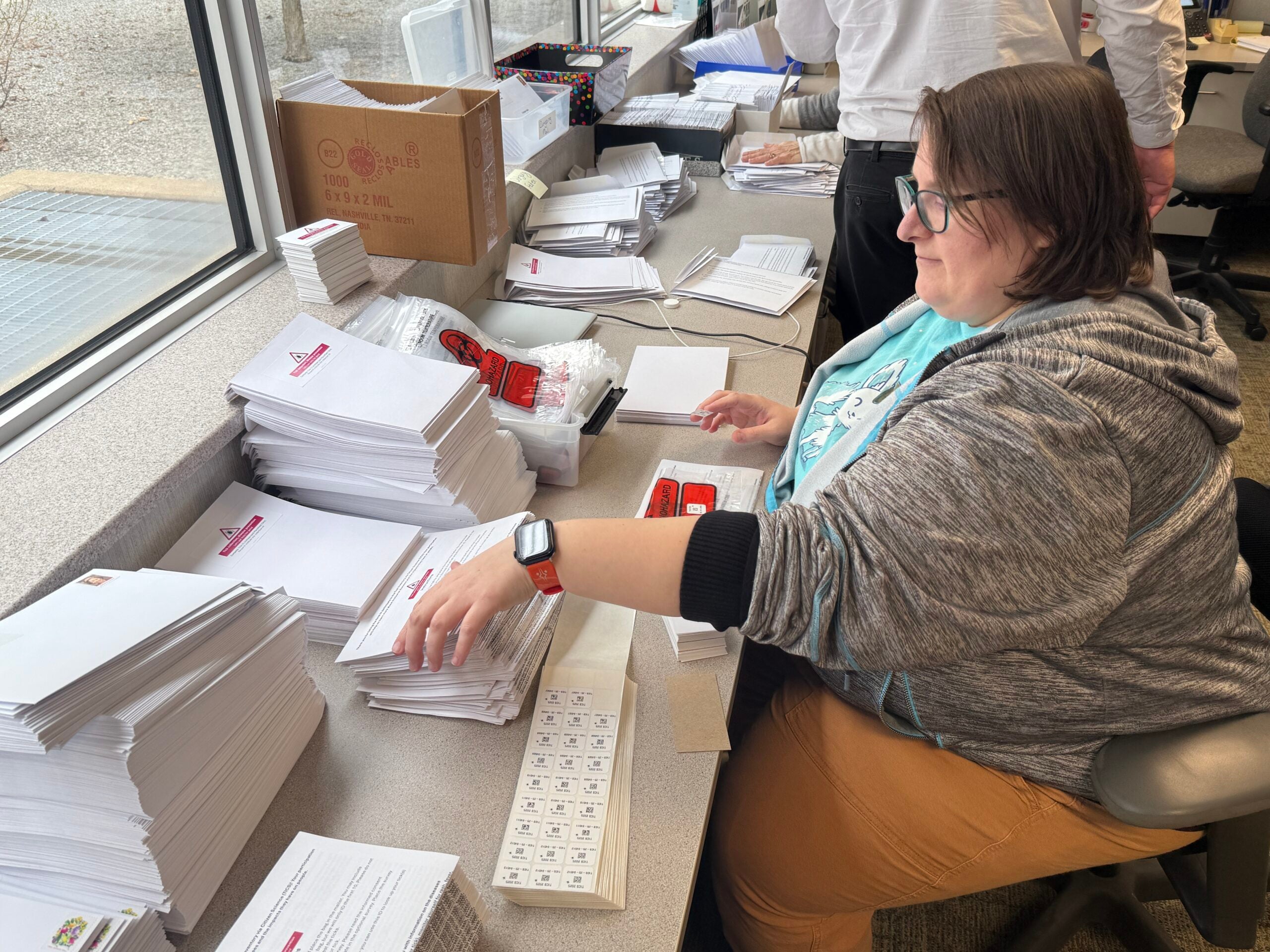

Through its Tick Inventory via Citizen Science, or TICS, initiative launched in 2024, the Research Institute is collecting ticks from people across Wisconsin in an effort to map out where different species are found and what pathogens they may be carrying. The response in the program’s first year far exceeded expectations, with more than 6,000 ticks submitted from nearly every county in the state.

Dr. Jennifer Meece, executive director of the Marshfield Clinic Research Institute, in a conversation with WPR’s Shereen Siewert on “Morning Edition,” said the program has proven to be a powerful tool in connecting science and public health with everyday people.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Science is about all of us,” Meece said. “Only through citizen engagement in a project like this can we actually do the meaningful work that we want to do.”

The goal of the TICS program is to assess the risk of encountering disease-carrying ticks and to better understand patterns of exposure in Wisconsin. Last year’s collection identified ticks typically found in warmer climates, such as the lone star tick — which can spread ehrlichiosis and trigger Alpha-gal Syndrome, a rare red meat allergy — and the brown dog tick, which is linked to Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Meece said the massive response in 2024 revealed not only the public’s interest but also the wide distribution of disease-causing ticks across the state.

This year’s effort, dubbed “TICS 2.0,” goes beyond collection. Participants now have the option to fill out additional survey questions, including what precautions they take to avoid ticks, whether they’ve been diagnosed with a tick-borne illness and whether they’re willing to be contacted for future studies. The goal is to build a research cohort to study long-term outcomes.

Residents can request a free, pre-paid tick collection kit by contacting the research team at tics@marshfieldclinic.org or calling 715-389-7796 ext. 16462.

The following interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

Shereen Siewert: Tell us how the program began.

Jennifer Meece: We have been interested in tick-borne infectious diseases for a long time. I mean, we live in Wisconsin, in a very highly endemic area for a number of tick-borne infectious diseases.

Being part of an integrated health care system, it was very important for us to think about ways that we could educate, because education can lead to prevention. And it also has been a really important way to connect everybody, every single person who lives in the state of Wisconsin and beyond. We’ve actually had contributors beyond the state of Wisconsin. This is a really important way for us to connect with our communities, our patients, our friends and our neighbors to help them realize that science isn’t scary.

SS: You took in thousands of ticks last year. What did you learn?

JM: When we launched this, we looked at other programs across the country and had some conversations with colleagues. Through those discussions, we thought initially that if we got 500 ticks we would be in good shape. That number would be a big win for year one. As the year went on, the numbers just grew and grew.

The first thing we learned is that people are really interested in this work. They’re really interested in helping us. We get all kinds of great calls; we get all kinds of great emails. People want to tell their stories, and I think that’s really important. That’s that connection back to people. That’s one thing I learned.

The other thing we learned is that the ticks that cause diseases are in virtually every county. Those ticks we collected last year have been identified and preserved in our freezers. This year, with this study, we are starting the journey of testing some of those ticks for the diseases that they carry. Our goal around that will be to better understand the infection rate in ticks. Is it 1 in 10, or 10 out of 10? Do ticks carry multiple pathogens? Are there environmental features that make ticks more likely to be present? We can do a whole lot with layers of geospatial information, temperature and climatology.

All of these things help us put together more predictive risk maps that show us not only where the ticks are being found, but also the burden of infection in those ticks. This is about preventing disease. We’d love it if tomorrow no one was ever subjected to Lyme disease because we got out in front of people, talked about prevention and what they can do to keep themselves at a lower risk.

SS: What are you concentrating on this year?

JM: This year, we’re calling it “TICS 2.0,” which will take us a level further. As we send out this year’s tick collection kits, we’ve included the ability for people to opt into a deeper level of engagement. They can consent through a form that we hope will eventually create a cohort of people who have had Lyme disease or other infectious diseases so that we can better understand their journey through time.

SS: Are you finding ticks now that you normally would have seen only in warmer areas of the country?

JM: Yes. If you ask people today who are in their 60s, 70s and 80s, they will tell you that as kids living in the northwoods of Wisconsin, they never saw deer ticks. It just wasn’t a thing. They weren’t present here. At some point, those ticks were introduced to our region. Over time, the habitat became more suitable for them. And now those ticks are here, living and breeding, year after year. With a study like this, we can do this surveillance to help us prepare for new introductions.

The Lone Star tick is a great example. Last year, we did have some Lone Star ticks collected. We don’t know yet what that means, because some ticks take a trip with migratory birds, latching on and dropping off. We don’t know yet whether their populations are able to establish and survive over our harsher winter than what they see in their native habitat. Without studies like this, we would never know until it is too late. Invasive species tend to get established and then go crazy. The Lone Star tick is known to cause a syndrome known as the red meat allergy, so if a person comes to the doctor with these very rare symptoms of having an extreme reaction to eating red meat, we need our doctors to know that’s a possibility because the Lone Star tick is here.

I know one thing: If you don’t look for it, you’re definitely not going to find it. So that’s part of the other thing this study does. It helps us keep our eyes open for things we might not expect. Then, we can do the education that’s necessary on new disease diagnostics or interventions.

If you have an idea about something in central Wisconsin you think we should talk about on “Morning Edition,” send it to us at central@wpr.org.