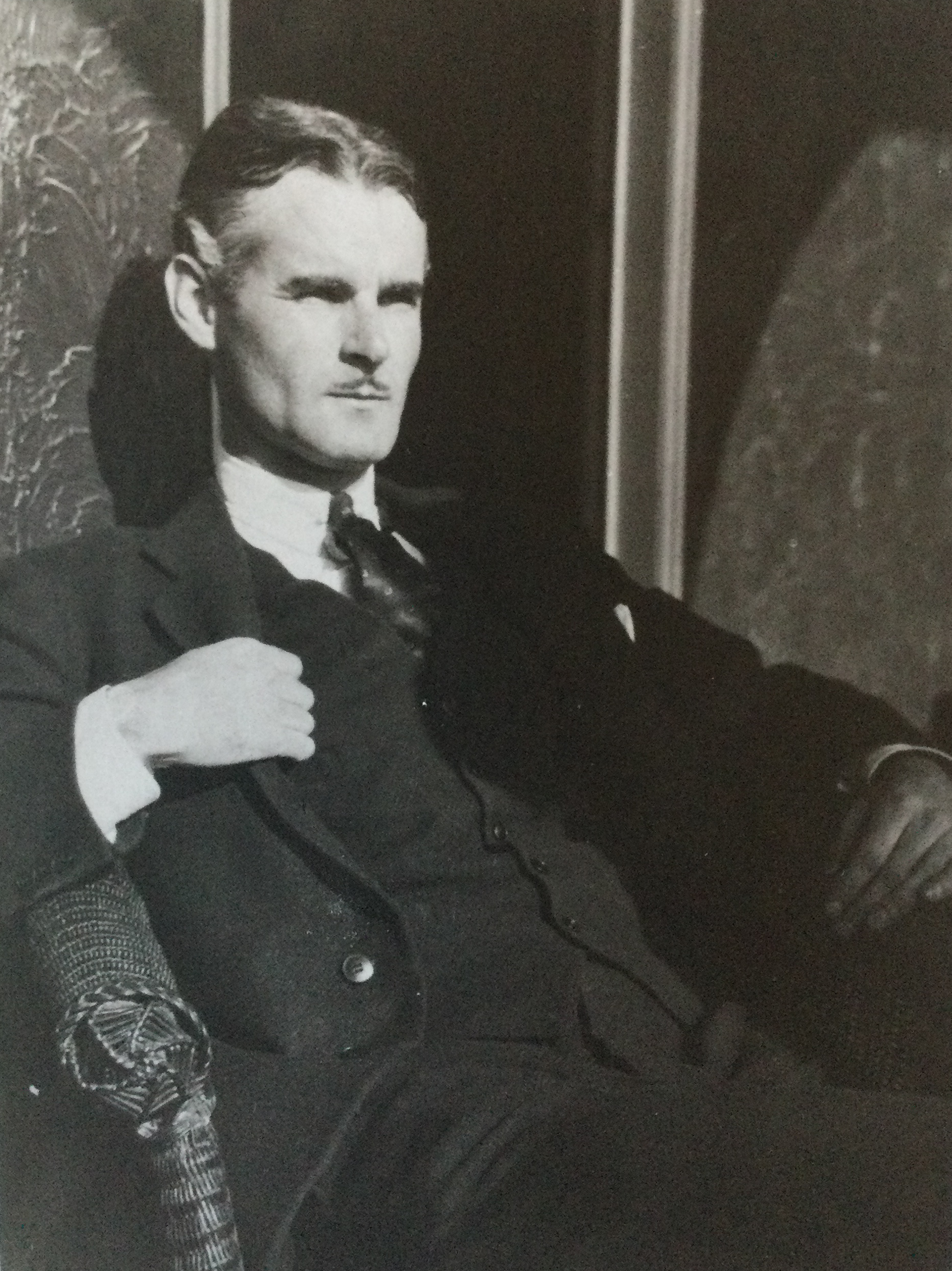

In 1902, the year before the Wright brothers first got their plane in the air, legendary bush pilot Robert Campbell Reeve was born in Waunakee, Wisconsin.

Reeve would become an aviation pioneer, mastering the dangerous art of shuttling supplies and people to and from the most remote parts of the Alaskan wilderness by taking off and landing on glaciers high in the mountains.

The fact that he lived through his many close scrapes was a wonder to Reeve himself.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I not only ran out of my own luck, but all my friends’ luck, and about 10,000 other people’s luck in the years I spent landing on those glaciers,” Reeve said in a 1961 interview with Ruth Briggs on the radio station KNIK in Alaska.

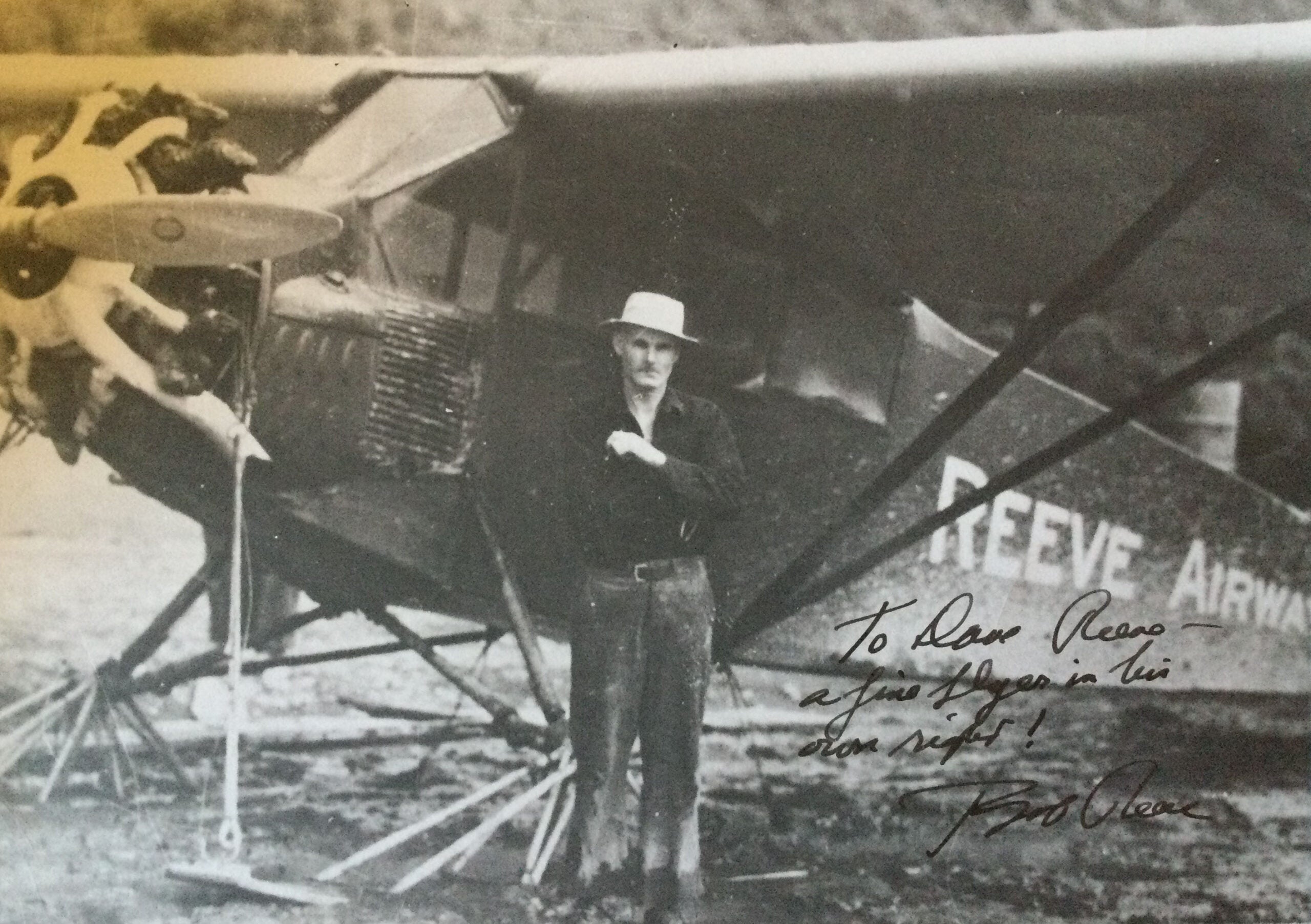

Reeve’s journey began in Wisconsin, but he soon left to explore the world, crashing planes and stowing away on ships to eventually end up in Alaska, where he would become an aviation legend and later establish an airline: Reeve Aleutian Airways. He was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1975 and the International Aerospace Hall of Fame in 1980.

His son, David Reeve, reversed his father’s journey: He left his home in Alaska to seek his fortune in Wisconsin, becoming CEO of Milwaukee-based Skyway Airlines and senior vice president of Midwest Airlines.

David joined WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” to talk about his father’s legacy in the world of aviation.

Flying away from Wisconsin

From a young age, Robert Reeve was on his own. His mother died when he was 2, and when his father remarried, he and his twin brother Richard were largely left to themselves. For Robert, who was inspired by books about aviation, that meant trying to leave and see the world.

“Ever since I was 6 or 7 years old, I’d planned on running away from home,” Reeve said in an interview with journalist Sandy Jensen in 1976. “I always thought that there was something more to the world than the rolling hills around Waunakee, Wisconsin.”

When he was 15, he finally succeeded. World War I had started and he left Wisconsin on a train to enlist in the Army. He managed to convince a recruiter he was old enough to join.

“I had already figured out that, if I kept my mouth shut, that I could give an impression of being 18, 19 or 20 years old and get into (the) service,” Reeve told Jensen. “I found a picture of a girl with a couple of kids on there, and I told everybody it was my wife and kids. I had a certain great respect as a family man in my regiment.”

He earned the rank of sergeant at 16, and he was discharged after the war ended at the age of 17. After a failed attempt to re-enter high school, he hopped on a ship and traveled to Asia, where he spent a couple of years before his father asked him to come home and attend college.

Reeve started at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Law School in 1922. But he and his friends spent all their spare time at an airfield nearby, getting rides and flying lessons from barnstormers like Cash Chamberlain and Walter Bullock.

“The only thing he was learning in college was how to make bathtub gin,” David Reeve said. “He was an adventurous guy, and I think college kind of tied him down.”

College leaders decided to turn him loose. Six months short of graduation, they expelled Reeve for spending more time at the airfield than with his studies.

Testing his luck, from South America to Alaska

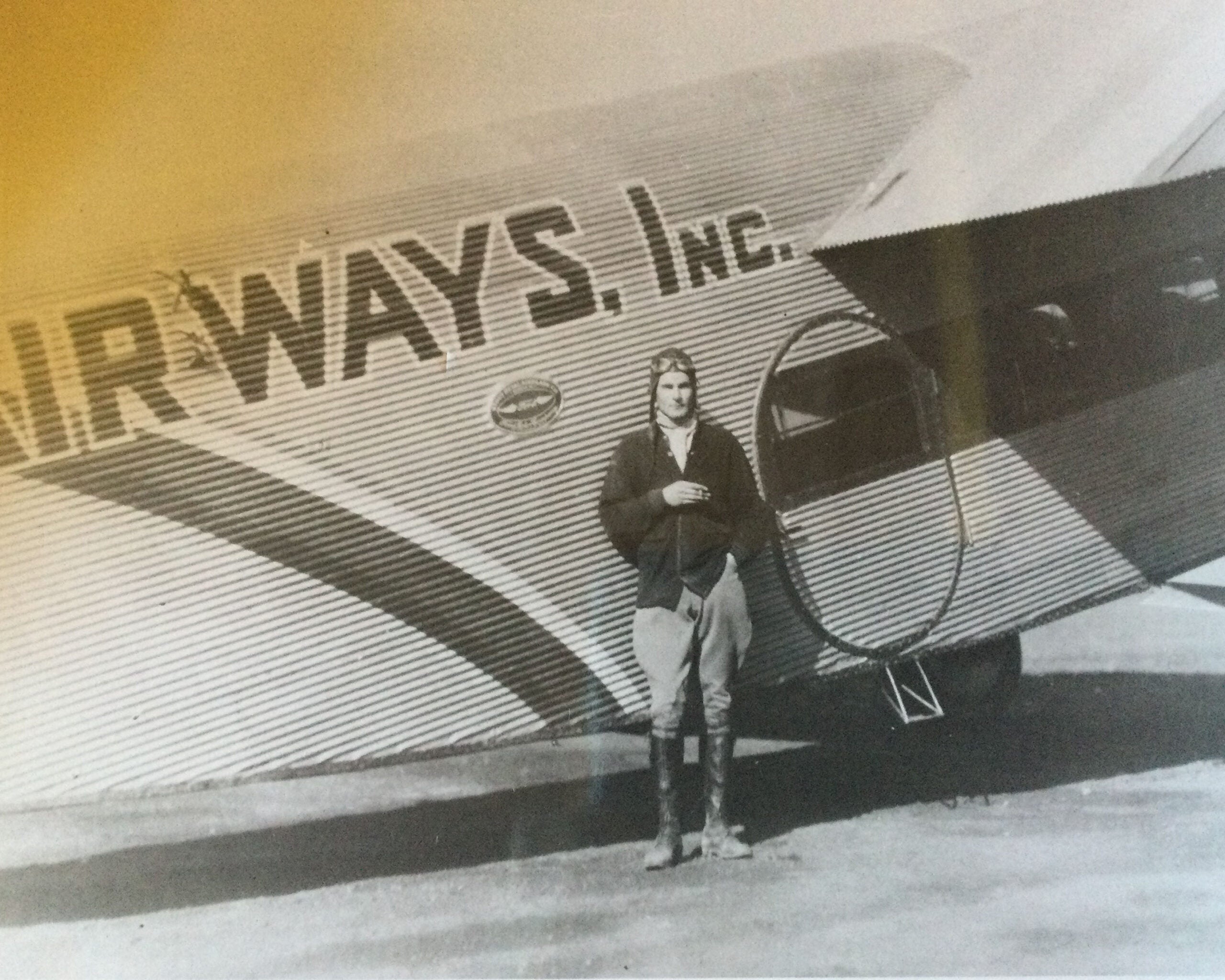

By 1926, Robert Reeve had earned his aircraft mechanic’s and commercial pilot’s certifications — the latter by getting lessons from barnstormers in exchange for a couple months’ work around a Texas airfield.

He gained experience with hazardous mountain flying in South America, where he got a job flying a 1,900-mile mail route over the Andes for Pan American-Grace Airways, also known as Panagra.

Then, Reeve caught a streak of bad luck.

“He claims he wrecked one of (Panagra’s) airplanes and he didn’t want to be fired, so he decided it was time to leave,” David Reeve said. “So he took his savings and put it in the stock market in 1929 and he lost it all.”

He returned to Wisconsin and contracted polio. By then, he’d had enough of life on the mainland.

“The next thing you know, he found himself on a freighter going to Alaska as a stowaway,” David Reeve said.

When Robert Reeve landed in Valdez, Alaska, he came across a broken Eagle Rock biplane, which he offered to fix in exchange for renting it from the owners. That’s how he began commercially flying and honing his bush-flying skills in the mountains of Alaska.

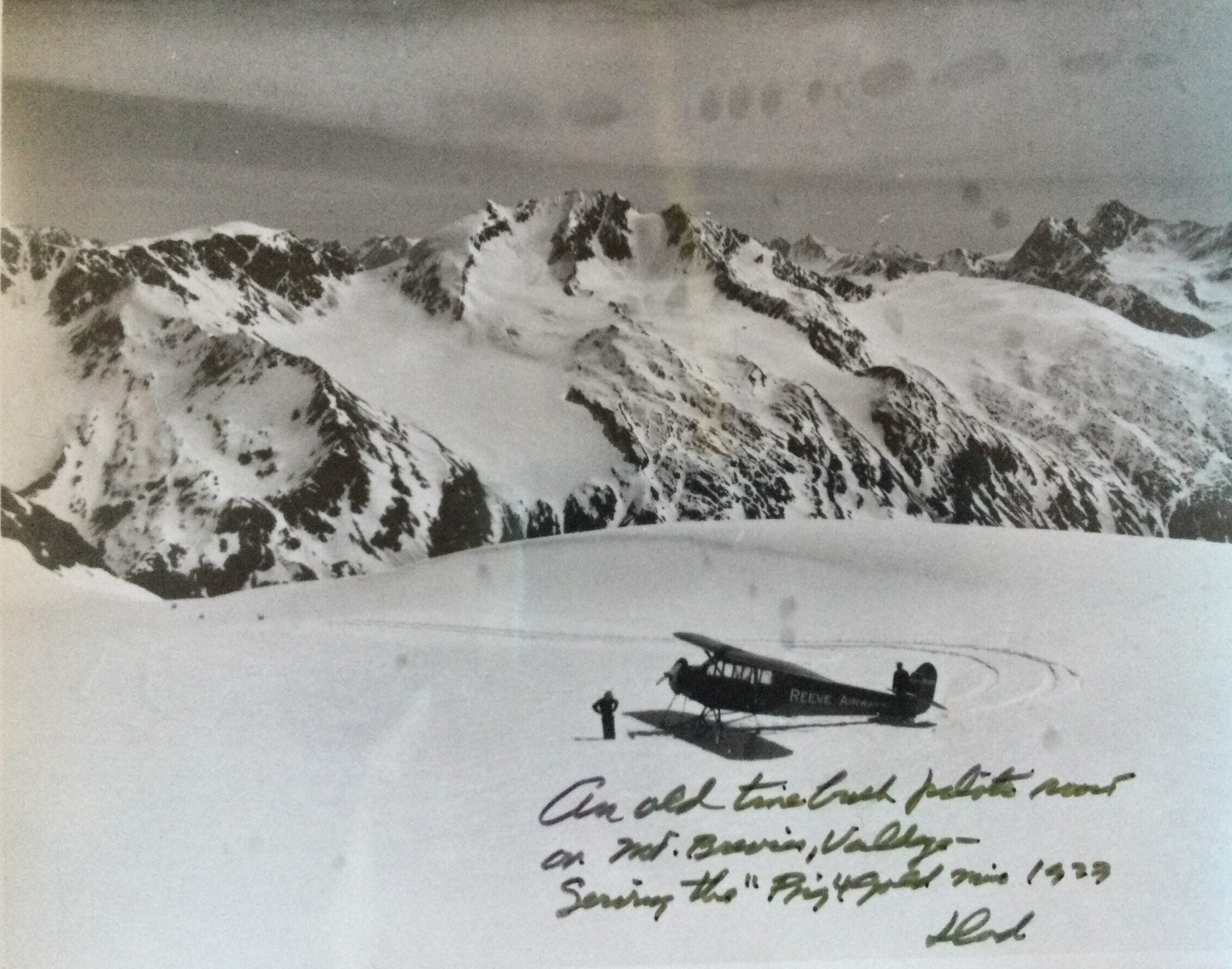

In the process, he found a niche he could fill: carrying supplies and people to mines high in the mountains by landing on glaciers. He developed a method of flying planes to these locations in both summer and winter.

To land on glaciers, a plane needs skis. But in the summer, it was impossible to take off without snow below the mountains. So Reeve designed a set of skis for landing on glaciers that could also take off on Alaska’s slippery mud flats at low tide.

“That’s what he really became well known for,” David Reeve said. “He had to make a living, and (he) didn’t have any competition when he was doing that type of flying.”

It was dangerous work — although David Reeve thinks his father would call it “unique” instead.

Once, his plane sank up to its belly in the unexpectedly soft snow of a glacier. He and his passengers were stranded on the mountain for four days and nights before they managed to dig it out and take off from firmer ground.

Another time, he flew smack into the side of a mountain. Luckily, the snow softened the blow, but not enough to avoid catapulting his passengers into the cockpit with him.

And Reeve had countless other stories of having to make emergency landings in remote places after his engine quit on him. In those moments, his experience as a mechanic came in handy.

Reeve became known as “The Glacier Pilot,” making more than 2,000 glacier landings over his career. Some of his adventures were published in newspapers and he began receiving fanmail. One frequent writer was a woman in Wisconsin, who would eventually move to Alaska and became Reeve’s wife.

Inspiring a family of aviators

Robert Reeve would go on to fly as a civilian pilot for the United States in World War II before establishing Reeve Aleutian Airways, a commercial airline which operated out of Anchorage to the Aleutian Islands and Pribilof Islands until 2000. His son David said he worked seven days a week for most of his career and put practically every dollar he made back into the airline until after age 60.

Many of Robert’s children became involved in the business. His eldest son Richard took over the airline after his father’s death, his eldest daughter Roberta was a flight attendant and his other daughter Janice became the airline’s vice president.

David flew for Reeve Aleutian Airways, which kicked off his decades-long career in aviation.

“My dad never expected us to follow in his footsteps, but we were all interested in aviation. Maybe it’s in our blood,” he said.