In Chippewa County, the annual Wisconsin Farm Technology Days is wrapping up, and a 70 foot-long soil pit is creating an immersive experience in conservation.

“You get the earthworm’s view of the different soil layers,” said Tim Miland on WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

Miland is one of 400 exhibitors who attended the three-day farm event held on the grounds of Close Farms and the Chippewa Valley Music Festival in Cadott.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

As an area resource soil scientist, Miland works with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. He said a team of soil scientists dig the 4-foot-deep pit each year to teach people of all ages about soil structure and health.

“A lot of people take soil for granted,” he said. “People (see what) healthy soil looks like, actually touching it, smelling it. I think this is a perfect opportunity to get everyone involved.”

The following has been edited for clarity and brevity

Kate Archer Kent: How would you describe the soil demonstration?

Tim Miland: The pit is 70 feet long, with ramps almost 100 feet long. Once you get down inside, you can see the different soil layers. As soil scientists, we call these soil layers horizon.

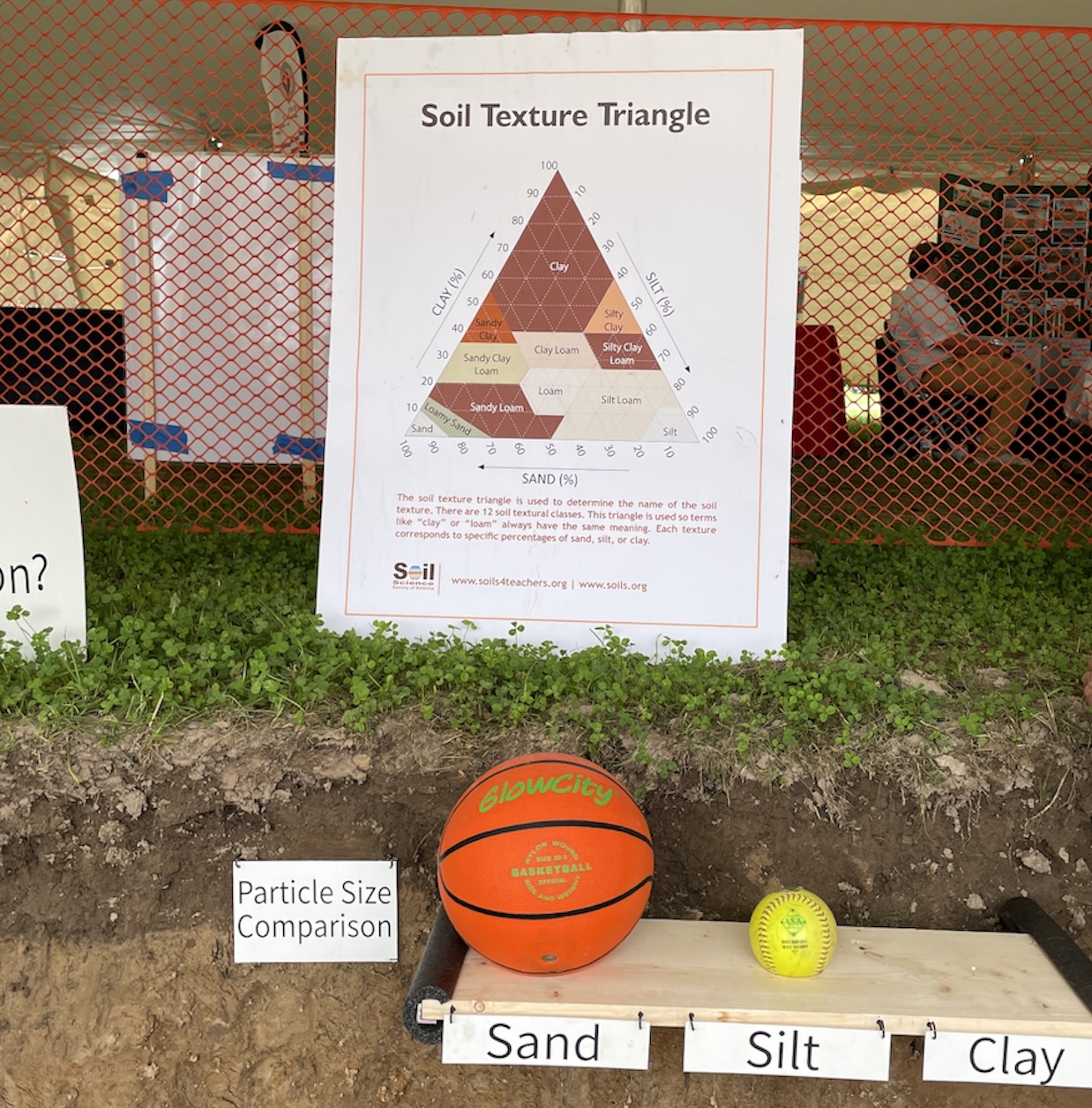

We have two different soil layers in there. We have a nice, fertile topsoil, that’s the texture of silt loam and down below we have a dense till.

The Chippewa Valley Music Festival grounds was historically a farm field. You can see the evidence of that. You can also see wormholes and roots that are penetrating through the soil.

These soils were deposited 12,000 years ago with the last glaciation. It’s really exciting to see the different features in a pit and the variation within those soils. We had a corn plant display, showing more of a conventional agricultural system with platy structures. It’s basically compaction from tillage and from the weight of farm tractors.

KAK: Is there a common question you get as you show people what is under our feet?

TM: I think people are just amazed at what you can see from a 70-foot-long pit. You can see all the activity four feet deep. A lot of times people ask, “Where did the soil come from? What is what? Why? What does it feel like?”

We’ll just hand them a sample and say, feel for yourself. Feel the smoothness of the loess, which is wind blown silt. They’re amazed at how deep night crawlers can penetrate into the soil.

We had rain and we actually had a little bit of a geyser coming into the side of the pit, because there was a night crawler hole outside in the grass, and it connected into the pit.

KAK: You oversee 21 counties in northwest Wisconsin. How would you describe the overall health of Wisconsin soils in your region?

TM: In the last 10 years, I’ve seen a lot more effort being put towards soil health. It’s not only the agricultural community, there are other private landowners as well.

People with lawns are planting more diverse pollinator gardens and a lot of farmers are incorporating cover crops and no-till systems. I think there’s room to improve, but I do think there are definitely steps in the right direction.

KAK: What are ways in which Wisconsin farmers are preserving their soil, especially top soil?

TM: There’s a lot of different things we can do like keeping things covered. So, cover crops, leaving residue in fields, using minimal tillage, trying to cut back wherever we can. Also, minimizing disturbances as far as chemicals or the physical features, and adding diversity.

Adding different types of cover crops, manure or cattle to the land also can help microbes activate the soil microbiota that are living there.

KAK: Adding manure or cattle to the land is a really sensitive issue because of the issues over runoff. What do you see there?

TM: I think part of it is just proper amounts and timing. Historically, in Wisconsin, there were many different animals, bison, elk, etc., that were also depositing manure. I think everything is a balance. It’s that common saying, “Everything in moderation.” I think those nutrients are very important to the soil.

KAK: The Natural Resources Conservation Service describes Wisconsin’s state soil, Antigo Silt Loam, as a productive, well drained soil. How could our state improve and protect the state’s soil?

TM: In 1983, University of Wisconsin-Madison professor Francis Hole petitioned the state of Wisconsin for Antigo Silt Loam. It is a very fine soil from the Antigo area. We actually have a roadside information sign there that talks about it. We even have a soil song.

When you think about it, soil is probably the most valuable resource we have. Every square foot of Wisconsin has a soil survey done on soil mapping, except for Milwaukee, and we’re currently mapping soils in Milwaukee.

People can access this information through the Web Soil Survey. It doesn’t matter where you live in Wisconsin or the United States, you can get that information to help you make really good decisions on utilizing and protecting your soil.