Juanita Adams grew up in Memphis, Tennessee, in the 1940s and ’50s.

She’d often watch as buses filled with white students passed by on her walk to school.

Separate schools. Separate bathrooms. Separate water fountains. Separate restaurants. Every aspect of Adams’ life was impacted by Jim Crow laws.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

After moving to Milwaukee with her husband in 1959, she quickly learned systemic racism was also affecting life for Black people in Wisconsin.

“Several years passed before we began to notice the segregation that no one talked about. Subtle, quiet injustices were happening all around us,” Adams wrote in “My Life as an Activist in Milwaukee,” an autobiographical account from 2014.

She decided to do something about it.

In 1965, Adams was outside the construction site for a planned segregated school on Milwaukee’s west side. Twenty-five years old and six months pregnant with her daughter Jacinta, she threw her body on a concrete mixer to halt construction of the school. Shortly after, she was arrested.

Nearly 60 years later, Adams is being recognized for her activism with a street sign next to the school she fought to block, a school her great-granddaughter now attends.

Adams died in 2016. But her daughter Patricia Cifax Adams said she is proud to see her mother’s activism recognized outside the building, now called Highland Community School.

“When I look at the school now, it’s like seeing the dream come to fruition,” Cifax Adams said. “Then, having her very own great-granddaughter be able to experience en excellent education there has just been amazing.”

A life of activism

Adams joined the St. Boniface Catholic Church in Milwaukee in 1962. That congregation was led by Father James Groppi, a prominent civil rights activist in Milwaukee. Adams and others soon founded the Milwaukee chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, which organized peaceful protests and sit-ins in the Milwaukee area.

In August 1963, Adams rode the bus to Washington to represent CORE during the historic March on Washington.

“When we returned from Washington, CORE members were energized and ready to hit the streets full force,” Adams wrote.

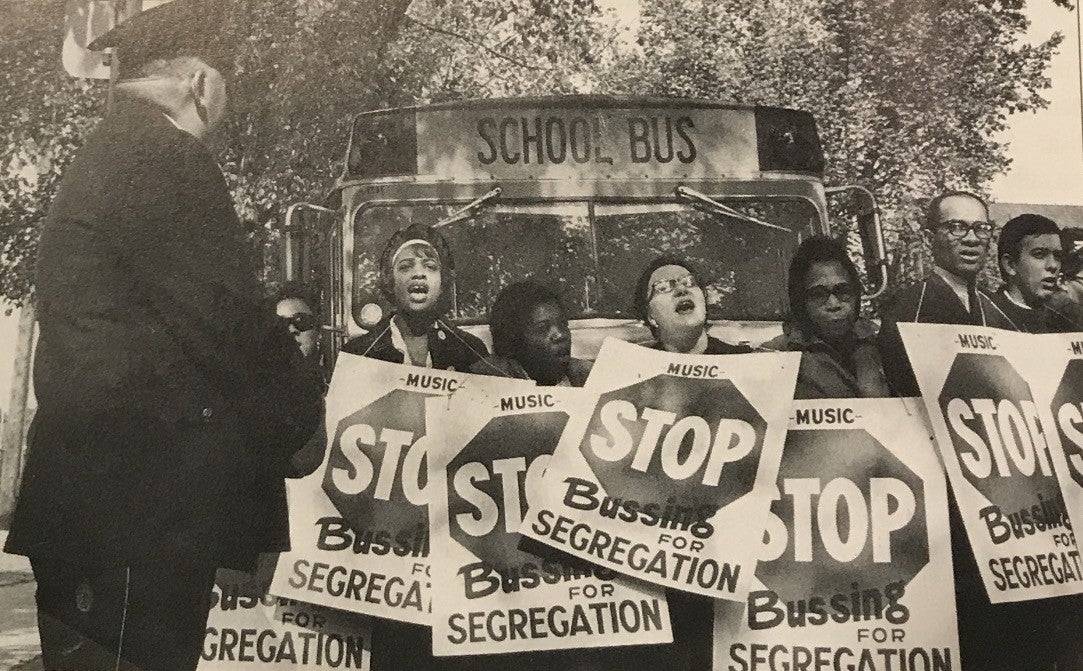

Adams worked with the Milwaukee United School Integration Committee. That group held demonstrations and protests, as many Black students in Milwaukee were forced to remain separate from white students in schools across the city.

“As a mother, this injustice felt particularly painful to me,” Adams wrote.

On Dec. 11, 1965, Adams and others were protesting the construction of MacDowell School, now known as Highland Community. The building under construction was designed to be a school mainly for Black children.

“The site was to be a school for Black children. We protested the building of the school, as it was intended to maintain racial segregation,” Adams wrote. That’s when Adams decided to run to the cement mixer.

Jacinta Adams said it was a moment her mother spoke about often.

“To think that she put herself on the line — and not only just herself, but her own unborn child on the line as well — for the cause …. when I go back in the same spot, it brings me chills, like wow, as a young woman, she did this,” Jacinta said.

In 1967, Adams marched with Groppi and many others during Milwaukee’s Open Housing Marches. On July 30, 1967, three people died and another 100 were injured during a riot that broke out during that march.

“The changing movement and the amount of time it took from my family motivated me to decrease my level of involvement. Two of my three children were in elementary school and needed my undivided attention. I decided it was time for me to consider the well-being of my own children, so I became a full-time, stay-at-home mother,” Adams wrote.

Even so, Adams continued to be a force for change in her community. She was a steady volunteer at the Sojourner Truth House and active church member until her death in 2016.

The sign

Sheila Adams Gardner is the youngest of Adams’ three daughters. She’s now an attorney and mediator in Washington. She was at Summerfest with her sisters last summer when they saw the director of Milwaukee’s Black Historical Society, who encouraged them to attempt getting a street sign in their mother’s honor.

“Up until that moment, we hadn’t really considered it,” Adams Gardner said.

But after learning that Cifax Adams’ granddaughter goes to the school now, they decided it was “kismet.”

“In that moment, we all got the chills, thinking my goodness, this would be perfect,” Adams Gardner said.

Cifax Adams has also been working as a Montessori coach at the school. She said the school is preserving Adam’s history. Just last week, she shared her mother’s story with students at the school.

She’s encouraged by the diversity of the student body. According to the most recent demographic data from Milwaukee Public Schools, about 45 percent of students are Black and 42 percent are white.

“I look at the diversity that is there now, and I think, ‘Wow, this is what Mom was fighting for.’ (Because) at the time, when they were building MacDowell, they were building it to be another segregated school,” she said. “When I look and go to Highland, I do get a sense of hope.”

The city approved the street sign last fall.

From mother to daughters

Adams’ daughters said their lives have all been shaped by their mother’s activism. Their father, Cleo Adams, also encourages them, as he owns one of the city’s oldest Black owned businesses, an auto body shop on the north side.

Cifax Adams has spent her life, much like her mother’s, working to improve education for others in Milwaukee. She’s a retired principal for four different schools in Milwaukee Public Schools and is now the director of strategic initiatives at City Forward Collective, a Milwaukee nonprofit focused on eliminating educational inequities.

“She often said she did it for us, and for others, so I have carried that mission on,” Cifax Adams said. “I want to provide the best education for others, and I feel like I did my best.”

Jacinta has worked at Milwaukee Public Schools for nearly 30 years as a special education teacher.

“With her activism, and the things that she had instilled in us, I in turn fight for my special education students as well, so that they can have that same type of equity,” Jacinta said.

Adams Gardner said she’s also using her skills to make others lives better.

“The idea of community is very important to us. The idea of being creative in your way of making life happen, sticking up for what’s right, being there for people who need help, supporting women — all of those things were very important,” Adams Gardner said.

If their mother was here to see her work recognized, Adams Gardner said, she would most likely try to turn the spotlight on someone else.

“If she were alive today and all of this was going on, somehow, she would turn this around and the attention would not be on her. It would be on other people, or it would be on the cause,” Adams Gardner said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.