Before the COVID-19 pandemic struck Wisconsin, a typical work day for Merta Maaneb de Macedo entailed crisscrossing Dane County to visit expecting mothers in their homes and provide them with information to aid in healthy pregnancies, deliveries and early lives for their newborns.

Now, Maaneb de Macedo spends her days — and nights and weekends — cold-calling dozens of strangers to give them potentially alarming news: They have been exposed to COVID-19 and should quarantine themselves at home for up to two weeks and monitor for symptoms.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Maaneb de Macedo is a part-time public-health nurse turned full-time COVID-19 contact tracer for Public Health Madison & Dane County. She is one of hundreds of public health foot soldiers around Wisconsin whose mission involves sharing sensitive, urgent and sometimes unwelcome health information with strangers over the phone — provided they answer her calls in the first place.

As the pandemic wears on, the work of contact tracing will become only more important and more challenging as this small but growing army increasingly bears the burden of slowing COVID-19’s transmission in Wisconsin.

‘Safer at Home’ to ‘Wild West’

On May 13, 2020, Wisconsin lurched out of a stay-at-home order that had shuttered many businesses and curtailed public life for seven weeks in a bid to pump the brakes on an outbreak of a deadly and not well understood new disease. The policy’s end came abruptly, when the state Supreme Court decided along mostly familiar ideological lines that Gov. Tony Evers and his administration had acted beyond their legal authority to control infectious disease outbreaks by extending the order beyond its initial expiration date.

Blunt as it was, the order dubbed “Safer at Home” was until that point the state’s primary tool for fighting COVID-19 as officials sought to shore up Wisconsin’s healthcare infrastructure. The immediate goal was to withstand a sustained onslaught of the disease that has strained health systems from New York City to New Orleans to Detroit, and has been estimated to have killed at least 92,000 Americans in barely three months.

In cutting the stay-at-home order short, the state Supreme Court’s decision upended the phased plan for easing restrictions put in place by Evers administration and Wisconsin Department of Health Services. That plan was set to kick in once public health officials deemed COVID-19 sufficiently controlled through the status of six “gating criteria” intended to indicate whether Wisconsin was adequately prepared to handle any rise in new infections.

Scenes from across Wisconsin of bars packed with maskless patrons only hours after the order was overturned prompted Evers to refer to the state as the “Wild West” on national television. The social gatherings also drove home a sense of urgency among public health officials preparing for a broader spread of COVID-19, even as public health departments for Wisconsin’s largest cities issued local stay-at-home orders within their own jurisdictions.

Their preparations have included ensuring that hospitals have the beds and personal protective equipment necessary to safely handle a potential influx of COVID-19 patients. This work has also entailed major expansions of the state’s capacity to test for the disease, as well as to identify the close contacts of residents who test positive, warn them of their exposure and offer resources to aid in quarantining should they need them.

Until there is a safe, effective and widely available treatment for COVID-19 — or better yet, a vaccine that can prevent infection in the first place — controlling the disease will depend in large part on these two time-honored public health strategies: testing and contact tracing.

Indeed, as the response to the pandemic shifts from acute crisis mode to ongoing management, “test and trace” has become a common refrain of public health officials as they describe what needs to happen to keep the virus, and more disruptive measures, at bay in the coming months and years.

Boxing in COVID-19

Contact tracing is nothing new for Wisconsin’s 92 local health departments. Public health professionals regularly employ the strategy to curtail the transmission of many common communicable diseases, including sexually transmitted infections.

The practice of identifying and reaching out to people who have had close physical contact with someone who has been diagnosed with an infectious disease is a public health mainstay, and has indeed been employed since COVID-19 started spreading around the United States. However this tracing must be followed up with voluntary self-quarantine or quarantine orders if it is to meaningfully slow the disease’s spread within and among communities.

Short of a cure or effective treatment for COVID-19, something that could take years to develop, state and local health officials in Wisconsin are planning for a future where contact tracing plays a central role in combating the disease.

“This is how we box in the virus and protect all of us, especially those most vulnerable to serious illness,” said Julie Willems Van Dijk, the assistant secretary of the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

The core idea is simple: Knowledge is power, and by providing information about their exposure to a disease and resources to respond, effective contact tracing empowers exposed individuals to seek timely healthcare and block further transmission of the disease. In the case of COVID-19, which is highly infectious and often spread by people who aren’t even aware they’re infected, this knowledge is all the more powerful.

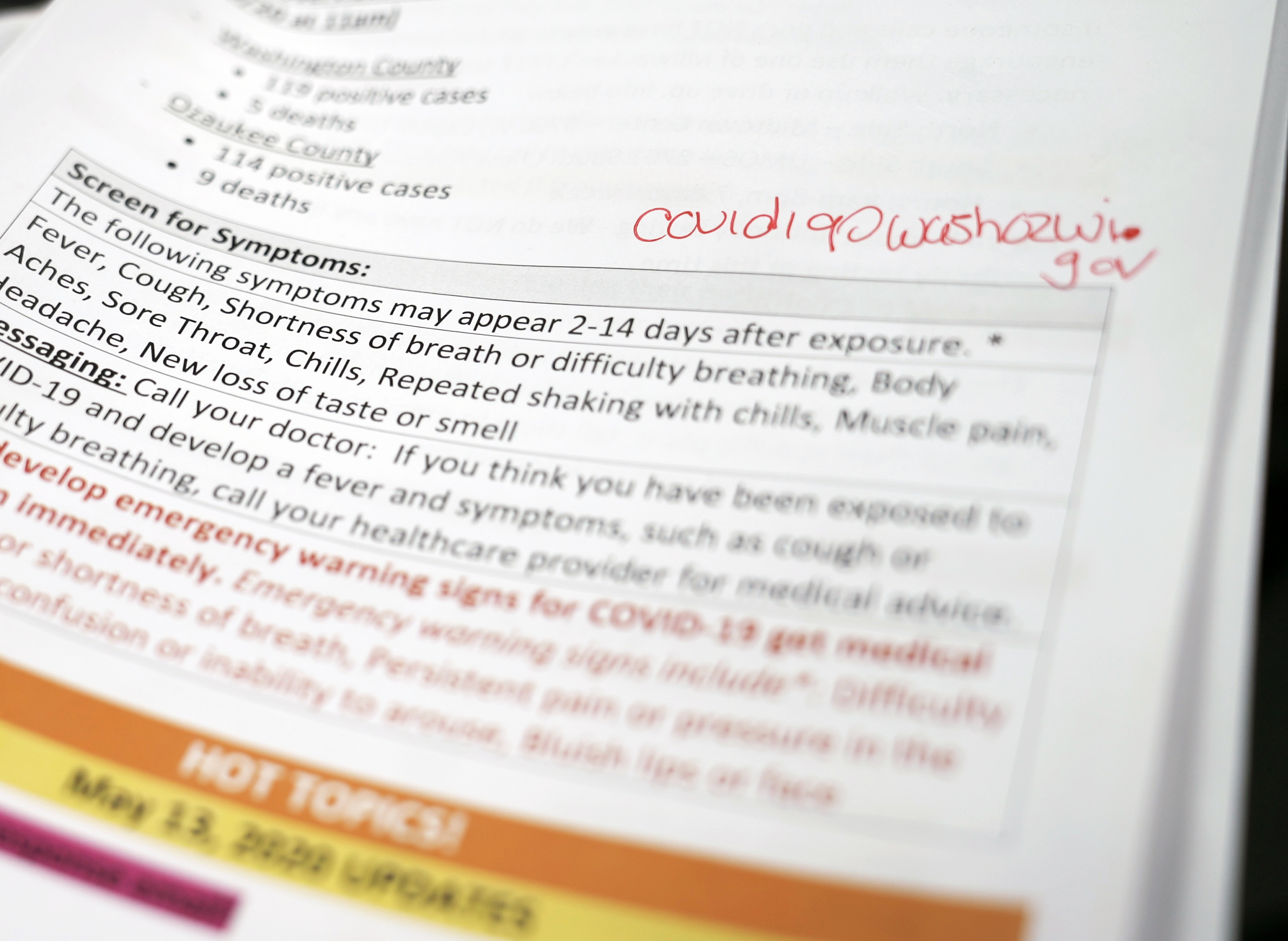

“If we can identify a positive case and the people who they were potentially in contact with, we can literally sort of wrap our arms around … that population, that pocket of people, and assure that they are no longer spreading the disease to others,” said Kirsten Johnson, health officer of the Washington Ozaukee Public Health Department, which covers two suburban counties north of Milwaukee.

After an initial rise in cases in late March, the two counties saw a decline in COVID-19 diagnoses through most of April, though cases began rising again in May.

But COVID-19 poses several challenges that complicate contact tracing.

First is the massive and geographically uneven challenge of volume. Contact tracing is usually conducted by local health departments. As has been witnessed time and again since the beginning of the pandemic, a relatively small local outbreak can in short order swell into thousands of cases and tens of thousands of contacts to reach. While the capacity to treat patients with serious symptoms at local hospitals has received attention, a sudden flare-up in new cases could also quickly overwhelm efforts to trace the contacts of confirmed cases, allowing a local outbreak to further snowball out of control.

This is a real possibility in the communities surrounding Racine if the outbreak there continues at the pace set in early May and more resources aren’t quickly secured.

“We’re really, really busy,” said Margaret Gesner, the deputy health officer for Central Racine County Health Department. The department covers all of Racine County outside of the city of Racine, where a rapidly growing outbreak has spilled into neighboring communities. As of May 19, Racine County had the second highest per capita rate of COVID-19 infections in the state, and a community testing site opened in the county on May 18, two days after a spike in new cases.

With only about 10 staff members devoted to contact tracing for COVID-19, the accelerating local outbreak has the potential to swamp the department’s efforts to track down all the close contacts of infected individuals. It’s why Gesner has sought additional funding to hire more tracers, both from municipalities within the department’s jurisdiction and the state. In the meantime, she said the department is doing what it can to speed up the process with the resources it has.

“We’re trying to be smart and strategic in terms of how we do the work,” Gesner said.

An established system

Contact tracing in Wisconsin begins as soon as one of the 50-odd labs that run COVID-19 tests in the state identifies a specimen as containing the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Positive test results are supposed to be entered as quickly as possible into the Wisconsin Electronic Disease Surveillance System, an online data management tool used by labs, public health departments and healthcare providers across the state that streamlines the process of reporting infectious disease diagnoses.

The surveillance system allows labs and healthcare providers to share limited information about the individuals who test positive for a host of infectious diseases like COVID-19, including their names and where they reside. This information is automatically passed on to the local health departments that have jurisdiction in the communities where each diagnosed individual lives, and it kickstarts the contact tracing process.

A case investigation is at the center of contact tracing. These investigations can look different depending on where the infection occurred. If a diagnosis coincides with other infections in a single workplace or other settings where people live or regularly spend time with others outside of their immediate household, including correctional facilities, homeless shelters and daycares, health officials operate under the assumption the cases are connected.

These connected diagnoses, as well as any single confirmed case at a long-term care facility, trigger a facility-wide public health investigation that often includes mass testing and direct assistance from the state. As of May 13, there were 299 facility-wide investigations tied to COVID-19 in Wisconsin.

On the other hand, when an individual’s diagnosis can’t be connected to a workplace or group living situation, the local health department begins a single case investigation by contacting the infected person as soon as possible and interviewing them.

This interview is standardized across the state and can take up to an hour to complete. It’s designed to glean information about an infected individual’s symptoms and any places they were since they started experiencing symptoms and during a 2-day period before their onset. It’s in this interview that investigators assemble a list of the individual’s close physical contacts during the period they were possibly infectious.

For COVID-19, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers a close contact to be anyone who has been within six feet of an infected individual for at least 15 minutes during a period spanning 48 hours before they began noticing symptoms and until their symptoms resolve. Since it often takes several days to confirm a COVID-19 diagnosis after someone begins feeling sick, contact tracers are tasked with trying to pin down every person with which someone has had close physical contact for a period that could have begun a week or two prior to the interview.

This list is then handed off to a contact tracer whose job it is to reach out to these close contacts of the infected person. Without divulging identifying information about the person diagnosed with COVID-19, the tracer informs these contacts of their exposure, instructs them to quarantine at home for two weeks, provides them with information about the disease, and asks if they’re experiencing any symptoms. Depending on their answers, these interviews could prompt a whole new round of phone calls.

“If contacts are symptomatic, we instruct them that they need to go in and get tested and isolate, and then we end up doing contact investigations with them as well,” said Linda Conlon, health officer for the Oneida County Public Health Department.

Oneida County has had only seven confirmed cases of COVID-19 as of May 19. Still, Conlon said the work of tracing contacts can be time consuming when people who are diagnosed with the disease weren’t practicing physical distancing during the period around their infection.

“A couple of our positive individuals have had a lot of contacts,” she said, adding that the department’s staff of eight trained contact tracers is preparing for future cases to have a similarly high number of contacts.

“We are expecting that there are going to be a lot more contacts with our individuals now that the ‘Safer At Home’ order has been lifted,” Conlon said. “Although people are still encouraged to only go out for essential things, we are noticing that with more movement, there are going to be obviously more people that will have contact with that [infected] individual.”

Emerging epidemiology

A particular challenge unique to contact tracing for COVID-19 is its status as a new disease. New information about the array of symptoms it causes and how it can spread is constantly being evaluated by health authorities at the CDC and state Department of Health Services. Some of this new information has the potential to majorly impact contact tracing.

“The problem with COVID is that because it’s so contagious before symptoms arise, the contact tracing gets pretty complicated,” said Patrick Remington, an epidemiologist and professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health. “If somebody gets diagnosed today, I have to think about where they were 10 days ago and every place where they might have come within six feet of an individual.”

This becomes all the more complicated as more businesses reopen across much of the state and many people relax their physical distancing habits.

“Now all of a sudden, when somebody gets diagnosed in a community where basically people have gone back to going out to restaurants, to bars, to hair salons, and now you say, ‘Tell me everywhere you’ve been in the past 10 days,’ … that’s a nightmare,” Remington said.

“When you think about a disease like tuberculosis, or syphilis, or whooping cough, we’ve had hundreds of years to learn about those diseases,” said Julie Willems Van Dijk, assistant secretary of the state health department. “We know exactly what the incubation period is. We know exactly the route of transmission. We know exactly the risk level of transmission. So the kind of interviews we do for those diseases are pretty much — I don’t want to say set in stone because we’re always learning — but they’re very standard and based on lots of experience.”

That is hardly the case with COVID-19, and questions in Wisconsin’s interview protocols for case investigators and contact tracers are regularly updated to reflect new scientific findings.

“The interview we do with people, particularly with the person who has been diagnosed with COVID, is something that’s constantly evolving,” said Willems Van Dijk. “And then the way we evaluate the information is different based on what we’re learning about the disease.”

In the pandemic’s early stages, COVID-19 was thought to spread only by people with symptoms like a fever or cough. That idea has since been shown to be wrong. In fact, people without symptoms, or who have yet to develop them, are now considered to play a significant role in the disease’s transmission. Early contact tracing efforts didn’t account for that possibility and potentially missed many individuals who were exposed to the virus.

“That’s changing when the risk period is for the people that [infected individuals] may have been in contact with,” said Willems Van Dijk. “That’s a big thing.”

Shifting attitudes toward the disease

Contact tracers have to remain up-to-date on evolving information during the pandemic, which can be a challenge in and of itself.

“Every day. Every single day the information is accumulating, and it’s changing, and it’s shifting,” said Merta Maaneb de Macedo, the public health nurse for Public Health Madison & Dane County. As a result, every morning, the department’s contact tracers participate in a phone call where they receive updates about COVID-19 before getting to work. They also receive email updates from the department and partners at the state and CDC.

“Everybody can spend a good amount of time every day just making sure that we’re up-to-date on the info,” Maaneb de Macedo said.

One potential consequence of this dizzying information environment Maaneb de Macedo has witnessed first hand is a gradual but noticeable erosion of trust among a growing number of the contacts she reaches out to.

When she began contact tracing in mid-March, Maaneb de Macedo said nearly every person she called recognized the gravity of the situation and expressed a willingness to self-quarantine. As time passes by, however, she said she’s encountering more people who are dismissive about COVID-19 and the need for quarantines.

“Now, I think that … there are a bunch of people who think that they really do know better without you telling them anything,” she said. “So it’s a delicate balance. It isn’t always that I’m trying to say ‘I’m a nurse, and I know these things, and you’re not a nurse, and you need to listen and learn.’ What we’re really trying to make the relationship be is that we’re gathering information, and as we’re gathering information we throw in a little health education.”

Contact tracers may be in for an uphill battle convincing some contacts to self-quarantine or even participate in a phone interview as COVID-19 conspiracy theories abound on YouTube and elsewhere online, and as some Americans reject the use of emergency public health powers.

In Wisconsin, a Marquette University Law School poll released May 12 laid bare the increasingly ideological debate over the state’s response to the pandemic. The polling showed that while a sizable majority of Wisconsinites continued to support Gov. Evers and the state’s stay-at-home order, only 49% of self-identified Republicans were supportive, down from 83% in late March. Support for the Democratic governor’s order slipped a much more modest 5% among self-identified Democrats, down to 90%.

Maintaining the trust of Wisconsinites is top of mind for state health officials who are considering ways to speed up contact tracing as the state’s caseload grows and positive individuals are expected to generally have more contacts. The state’s goal is to interview anyone who is confirmed to have COVID-19 within 24 hours of their diagnosis, and to interview all of their contacts within another 24 hours. That often hasn’t been attainable with resources available to the state and local health departments, according to assistant state health secretary Julie Willems Van Dijk.

“We have got to get much faster at this,” she said.

Part of the solution will be hiring more contact tracers. The state has reassigned hundreds of state workers to help with contact tracing part-time, and received more than 3,600 applications for temporary full-time positions that officials hope can help shore up local resources when there’s a surge in cases. The first few dozen of these new hires began training on May 18, and the state has plans to add hundreds more in the months to come, depending on the trajectory of the pandemic in Wisconsin.

On May 19, the Evers administration announced that $75 million of federal stimulus funding would be allocated toward beefing up contact tracing in the state. An additional $260 million would be allocated to support testing efforts. Up to two-thirds of the funding allocated for tracing would go to local and tribal health departments to hire additional staff for conducting case investigations and contact tracing, according to a press release from Evers’ office. An additional $445 million is being allocated to support a stepped up response in the case of a surge in the disease later in the year.

Leveraging new technologies

Wisconsin health officials also see a role for technology in making contact tracing more efficient, and therefore, they hope, more effective.

To that end, in mid-May, the state Department of Health Services signed a contract with Microsoft to use the company’s Dynamics 365 software as part of its COVID-19 response efforts. Like the Wisconsin Electronic Disease Surveillance System, this software can help manage the flow of information between the state, labs, local health departments and healthcare providers, but unlike that system, it can also connect seamlessly with the devices of Wisconsinites who seek testing for COVID-19.

Building upon the early experiences of jurisdictions that are using the software elsewhere, including in North Dakota, Missouri and Washington, D.C., Wisconsin officials say they envision a system where the information collection that informs contact tracing begins as soon as someone seeks a test, whether they drive up to a community testing site or request a test through their healthcare provider.

This new system wouldn’t really change the information shared by people who are tested, assistant state health secretary Julie Willems Van Dijk said, but would create a more direct line of communication between a patient and public health investigators. It’ll also offer the option of completing a large portion of the interview process online before test results are ready.

“Some people would much rather just fill out the form online than sit through a whole interview being asked questions,” Willems Van Dijk said. “As soon as their test results come back, [the software] will immediately ping the contact tracers, look for that person’s completed interview form and or place the call to them so that we can do this in a much more timely manner.”

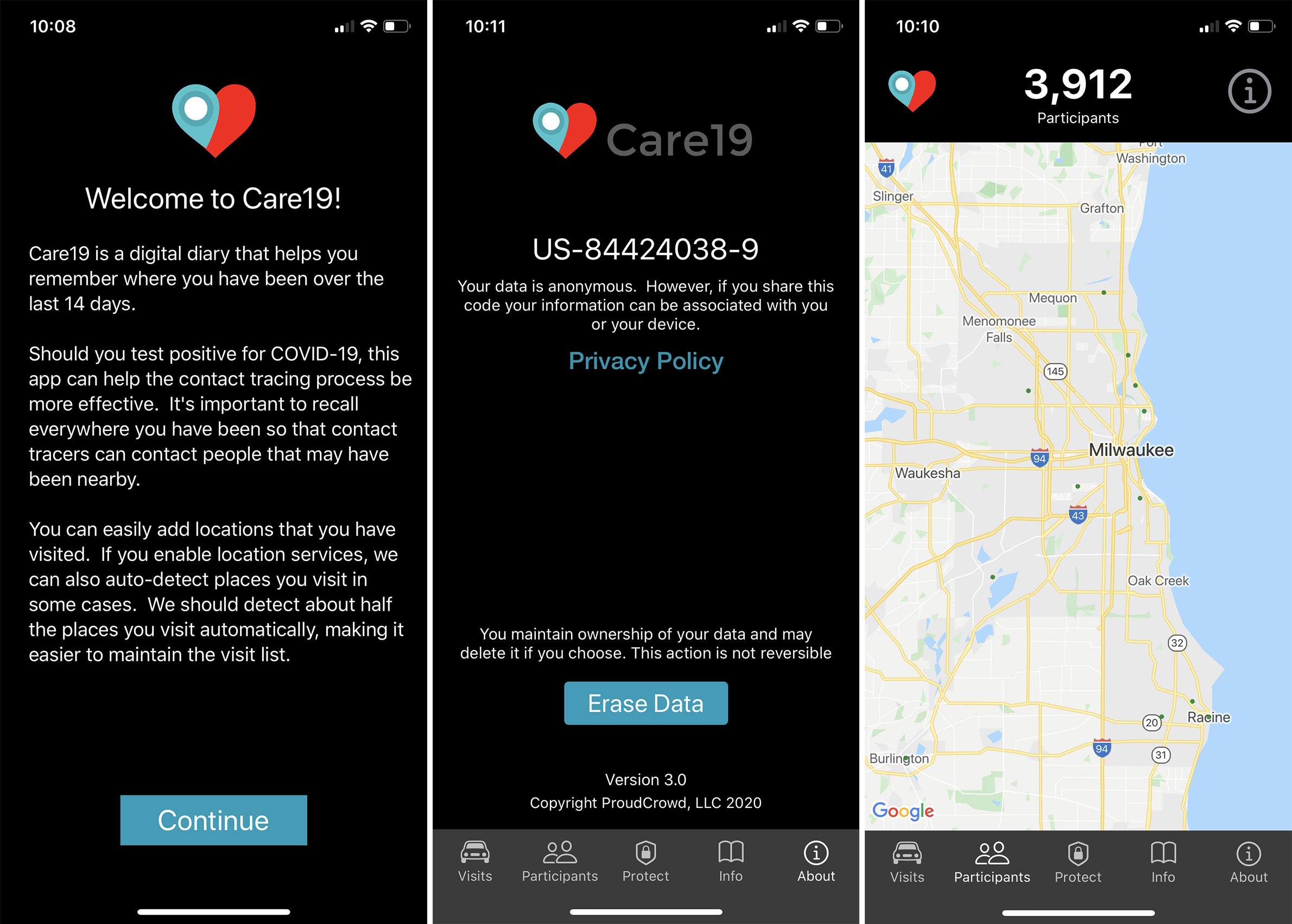

Additionally, Willems Van Dijk said the state is reviewing a number of smartphone apps that use location-tracking data to inform people whether they were in a location around the same time as someone who subsequently tests positive for COVID-19. Similar apps have sparked privacy concerns as some governments, including in South Korea, Singapore and Israel, have used them in invasive ways.

Willems Van Dijk said these so-called proximity apps could be a useful way of nudging people away from higher-risk habits.

“If I’m going out and doing a whole day of shopping and then my proximity tracer tells me I might have been exposed in five different stores, I might think, ‘You know, I don’t think I need to shop so much anymore, or maybe I’ll go back to online ordering.’”

A growing number of proximity apps are being developed for use around the world, though Willems Van Dijk said the agency is considering only those that can integrate with Dynamics 365. These include the Care19 app, which is already in use in North Dakota, as well as another app developed jointly by Apple and Google.

Underscoring the potential privacy risks of these rapidly developed apps and the need to closely vet them, a May 21 review by the software maker Jumbo found that North Dakota’s Care19 app violated its own privacy policy and directed users’ data to a third-party vendor without their knowledge.

In a May 22 statement emailed to WisContext, Willems Van Dijk said the state continued to evaluate contact tracing apps for ease of use and privacy protections.

“No decisions have been made yet, and we will consider the additional information regarding the Care19 application,” she said.

No matter which app the agency selects, Willems Van Dijk said its use would be optional and the privacy of users’ data would need to be ensured.

“That is one of the reasons we haven’t selected one yet,” she said. “We’re really looking at the different apps … and the privacy protection on them.”

In the end, though, technology can only replace so much of the work performed by an actual contact tracer, especially when an individual’s circumstances call for a sensitive and empathetic interaction.

“What sticks with me are the people who the cases that they have been associated with in close contact have been seriously ill, have died,” said Maaneb de Macedo. “The ability to kind of embrace them over the phone call and to tell them, ‘If you need to talk again, honestly just give a call or reach out,’ and some of those people that I know are struggling with family loss, I reach out to them every so often and say ‘Hey, how are you doing?’”

PBS Wisconsin multimedia producer Marisa Wojcik contributed to this story.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published on May 20 and updated on May 22 to include new information about privacy concerns over North Dakota’s contact tracing app.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.