Milwaukee Common Council heard from the city’s Health Department on Wednesday, two days after a report that was critical of Milwaukee’s lead abatement program was made public. But the gathering, which was scheduled to discuss the report’s findings, left elected officials with more questions than answers.

The internal audit from the Milwaukee Health Department said years of funding cuts and a lack of accountability stretched the program to its limits, often leaving lead-exposed children without appropriate follow-up testing services.

During Wednesday’s Steering and Rules Committee meeting, common council members were critical of what they called a lack of transparency, questioning even the timing of the report’s release and Mayor Tom Barrett’s response.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“When the mayor has a press conference at 7:15 on a Monday night that catches everyone by surprise, how are we in good conscience supposed to feel like we’re getting the straight scoop?” asked Alderman Mark Burkoswki.

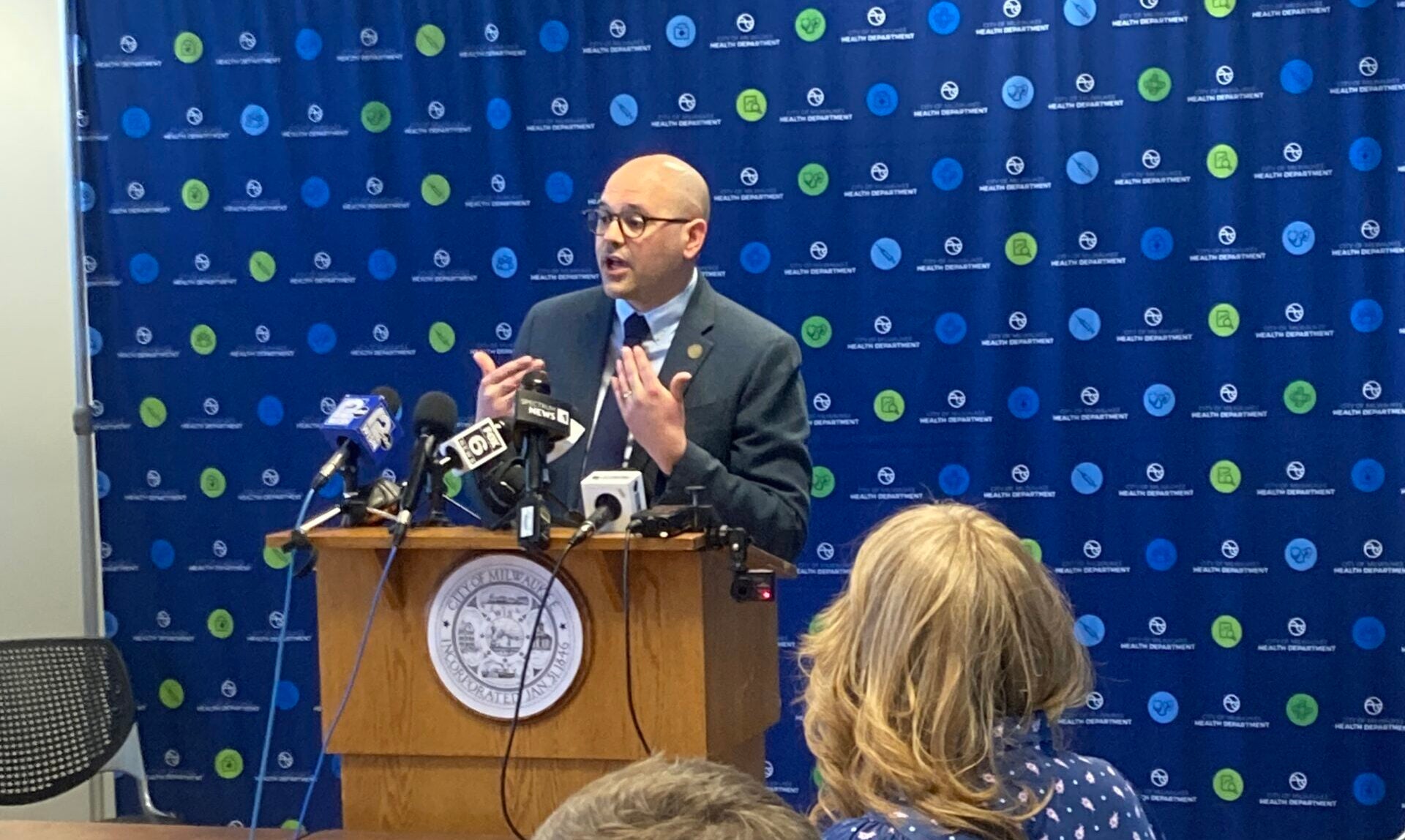

A spokesman for Barrett said the mayor wanted to make the findings public as soon as possible. Barrett called for a press conference just hours after he got the report which he ordered to be put together in 10 days.

Among the biggest points of concern for council members was the extent of lead exposure for Milwaukee children and how many remained untested.

According to the report, numbers from 2016 show 11.6 percent of children tested positive for lead levels high enough to require follow-up from the health department. That’s down from the 2003 numbers showing 37.9 percent of Milwaukee’s children were testing positive.

Dr. Geoffrey Swain, the interim medical director of the department, said the percentage of children tested has also improved somewhat in recent years but the problem remains extensive.

“Between 2000 and 2008, roughly speaking, there were typically 30 to 40 percent of kids under 6 that were being tested,” Swain said. “By 2011 that was closer to 50 percent, and it’s sort of stayed between 40 and 50 percent between 2011 and 2016. So are we testing all the kids? No.”

Council members were left asking what more could have been done to address the shortcomings.

“A lot of times we can say that we send out some piece of paper to peoples’ homes and we’ve got it on our websites, the answer to that is, it’s still not enough and we all know that,” said Alderman Jim Bohl.

City officials also wondered why staff didn’t blow the whistle if problems were so pervasive.

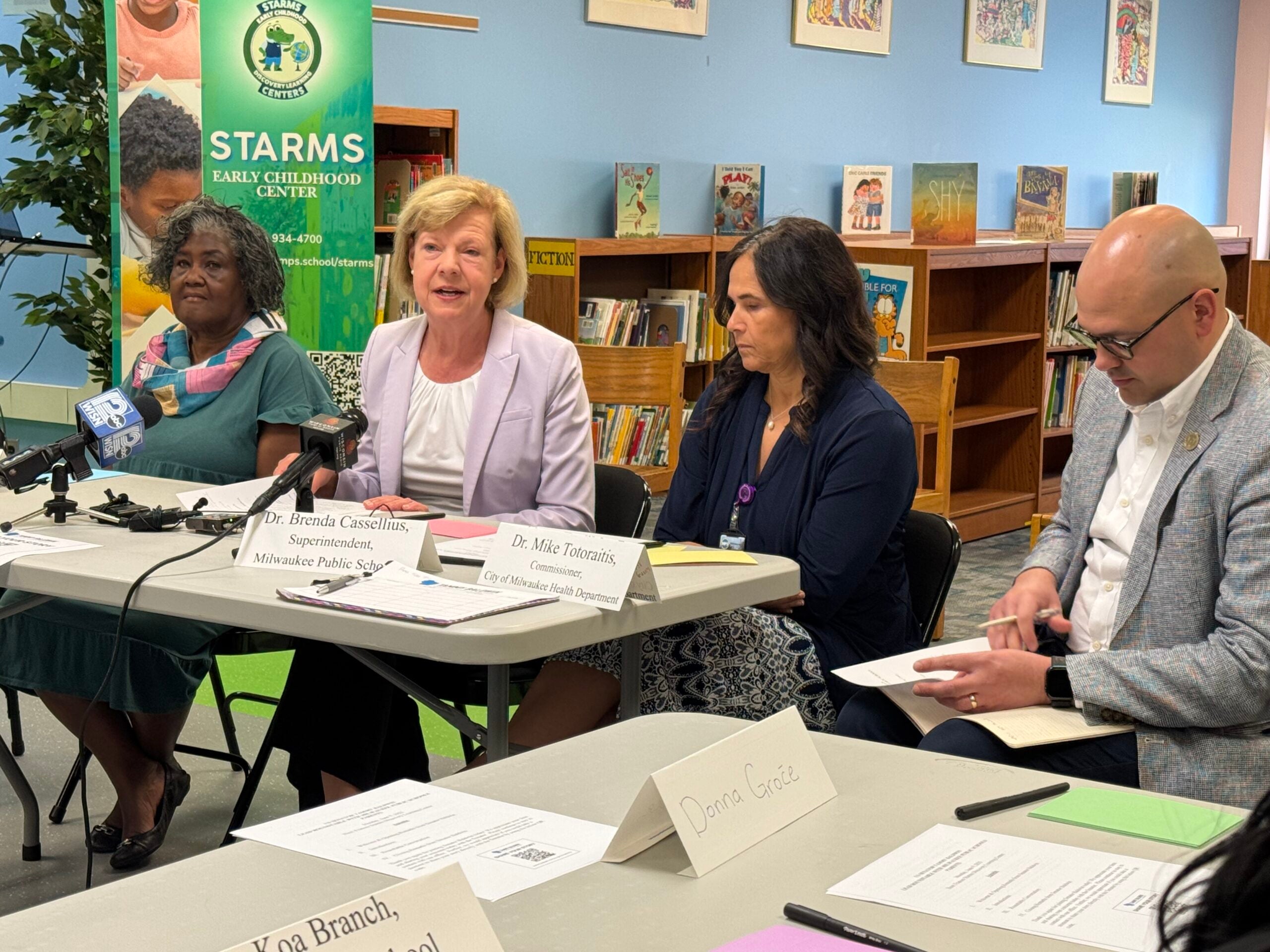

Angela Hagy became the city’s director of disease control and environmental health in June. She helps oversee the city’s lead program and helped put together the internal audit.

Hagy said a policy that prohibits staffers from speaking to the elected officials without approval from their direct superior is partly to blame.

“Unless he gives us the directive to contact you, it is department policy that we cannot contact you,” Hagy explained.

Bevan Baker, the former health commissioner, resigned in January when it was first learned the Milwaukee Health Department couldn’t confirm it had run the necessary follow-up for thousands of lead-exposed children.

The policy which some aldermen said they had heard of before, appears to have exacerbated the lead program’s deficiencies, said Common Council President Ashanti Hamilton.

“The lack of the ability to be able to move past your immediate supervisor to talk about a problem, hindered us from being able to respond to this in a quicker way,” Hamilton said.

Hamilton said members of the council were getting texts during the meeting confirming the policy. Council members say they want an ordinance to ban the practice.

The common council is launching its own investigation into the health department’s management of the lead program.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.