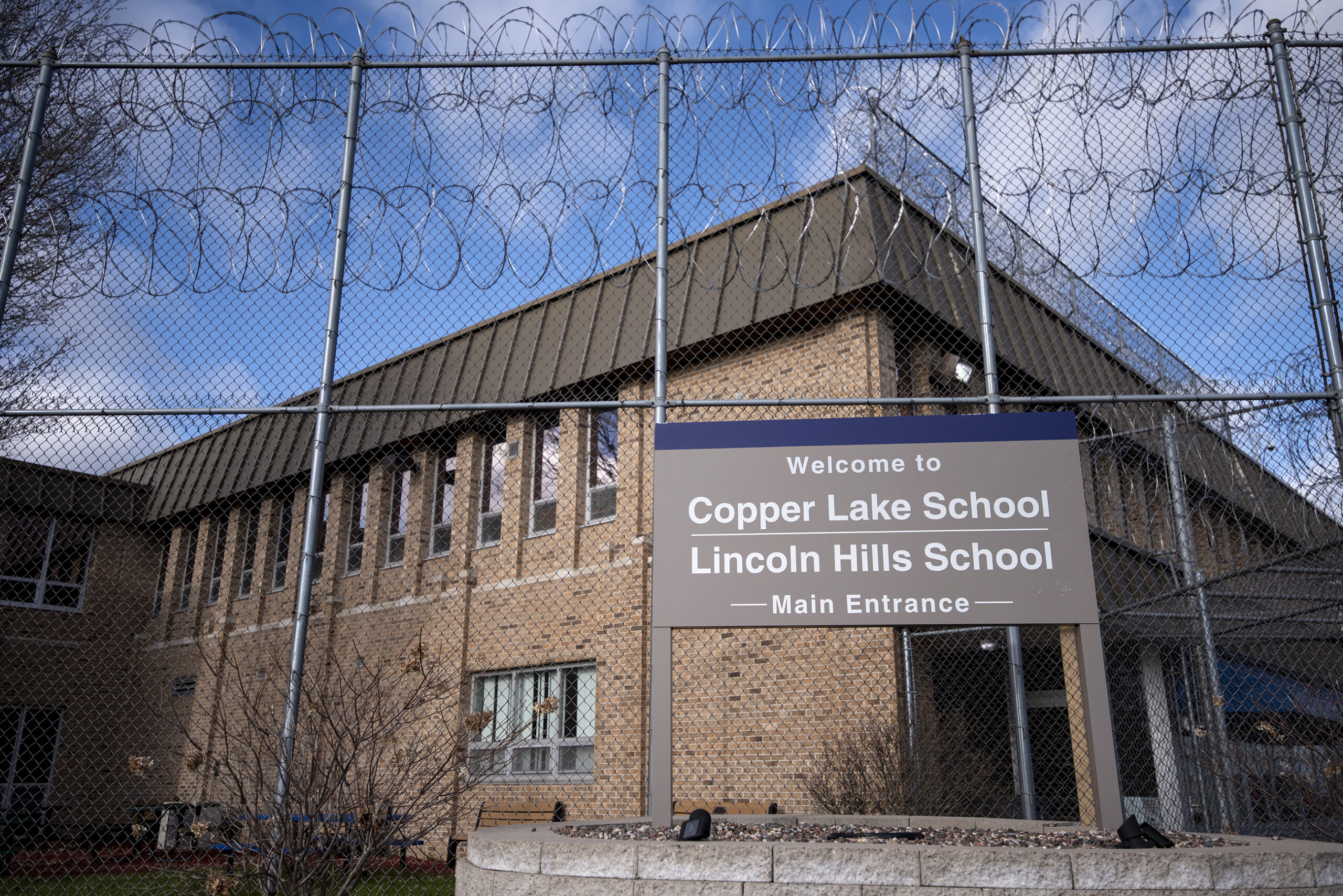

Children at the Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake youth prisons are no longer allowed to be locked in their rooms as punishment under the terms of a class-action settlement approved in 2018.

But kids at the northern Wisconsin facilities are still being confined to their rooms, simply because there aren’t enough staff members to supervise them, according to the latest report submitted by a court-appointed monitor.

Prison officials say they use so-called “operational confinement” to ensure the safety of the children and staff on days when not enough employees report to work to keep the facilities running as usual.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

American Civil Liberties Union of Wisconsin attorney Karyn Rotker says the youth confined to their rooms — sometimes for up to 20 hours a day — are left struggling with isolation. She says that’s especially difficult for those struggling with preexisting mental health issues and past trauma.

“In general, it doesn’t appear that the facility is doing this for quote-unquote, ‘punitive purposes,’” said Rotker, one of the attorneys who filed the federal class action lawsuit on behalf of the ACLU and the Juvenile Law Center in 2017. “But if you’re the youth who’s being told you have to stay in your room for 19 hours a day, or however many hours a day, it is not necessarily going to feel any different.”

Children miss out on in-person learning because of staffing

Children at the prison also say their education has been suffering because of inadequate staffing levels, according to the most recent monitor’s report which covers a period extending from August until November. Frequently, the youth weren’t able to report to their classrooms because not enough school staff showed up. Instead, students were stuck in their units filling out packets and workbooks or completing an online program on computer tablets.

Many students told the monitor they couldn’t “meaningfully learn” under those conditions and several said the requirements of their individualized education plans, which are federally-mandated for students with disabilities, weren’t being met.

“Youth are to some extent being expected to teach themselves, which is not realistic,” said Rotker, who joined the monitor on a site visit this fall.

In fact, the court monitor reviewed video footage from 26 random school days, and found students were not physically in the school area at all on more than half of those days.

As of Oct. 31, about a third of 19 teaching positions at the schools were vacant, along with more than one-fifth of 94 youth counselor positions, the monitor’s report found. The shortage of social workers was most severe, with 75 percent of social worker positions sitting empty. There were 78 children at both the Copper Lake and Lincoln Hills facilities at the end of October.

Although the facility hired 21 youth counselors between August and the end of October, it hasn’t managed to hire a new social worker since 2018, despite raising pay for the position. Nonetheless, the report referenced several recruiting efforts, including appearances at job fairs and walk-in interviews, and noted that the facilities has been trying to improve retention with employee wellness programs.

“This Administration will continue to seek every avenue to recruit new staff to Lincoln Hills/Copper Lake so we can safely meet the standards we have set,” Wisconsin Department of Corrections Secretary Kevin Carr said in a statement.

Lincoln Hills has been under scrutiny for years

After the federal lawsuit described abuse and civil rights violations at the prisons, Wisconsin’s Department of Corrections eventually agreed to the consent decree that’s currently in place at the Lincoln Hills School for Boys and the smaller Copper Lake School for Girls. Among dozens of other stipulations, it prohibits the use of pepper spray on children and limits strip searches while requiring probable cause for their use.

The treatment of youth at the prisons in the small, unincorporated community of Irma has been under scrutiny for years. That includes a Federal Bureau of Investigation inquiry into whether civil rights were violated at the prison, which ultimately did not result in any charges.

Then-Gov. Scott Walker signed a law in 2018 that would have required the Cooper Lake and Lincoln Hill schools to eventually be shuttered by January 2021, although that plan languished when state lawmakers failed to fund an alternative. Officials extended the deadline for closure by several months until summer 2021, but the state missed that deadline, too.

State plan for new facility in Milwaukee pending approvals

In August, Gov. Tony Evers announced the state had selected a site in north Milwaukee for a new youth detention facility, although that plan is pending approvals.

Rotker supports building a new facility in Milwaukee, in part because she hopes locating it in a more populous area of the state will make it easier to recruit and retain staff.

And she says the facility’s “fairly isolated” location appears to have been compounding feelings of isolation for many of the youth at the prison. Irma’s population hovers at less than 1,300 people and it’s more than 200 miles away from Milwaukee, where many of the incarcerated children have families.

“We need to bring these youth closer to home, which will also help provide more culturally relevant services for a lot of these kids,” Rotker said.

But Rotker says she hopes the states will rely less on incarcerating children.

“We need to fund and provide more alternative services so that they don’t have to be locking so many youth up,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.