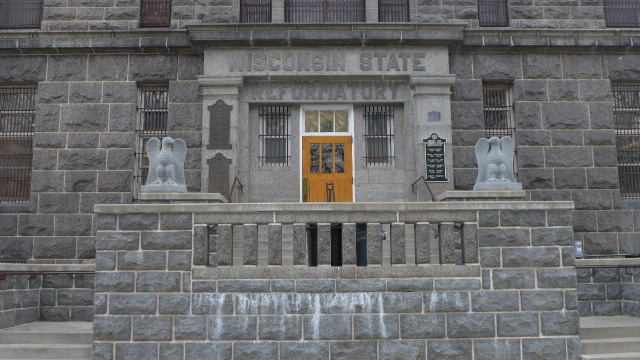

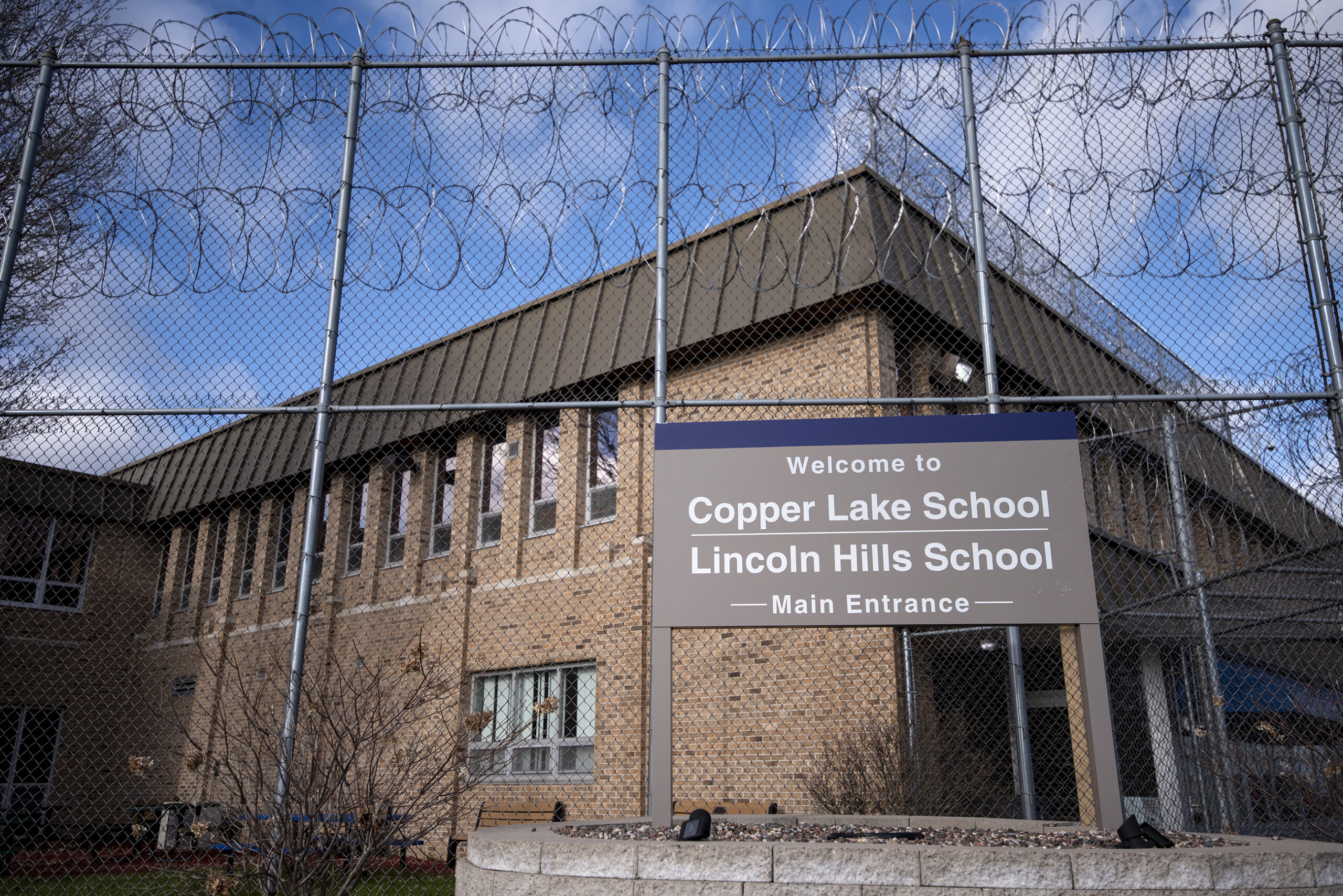

In the spring of 2018, then-Gov. Scott Walker signed a plan into law that would have closed the Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake youth prisons in January 2021, replacing them with community-based secure facilities. The hope was to keep incarcerated children closer to their families.

Then, in 2019, Gov. Tony Evers moved that deadline to July 2021.

Nearly three years later, plans to meet the July deadline have stalled out, even as the latest report from a court-appointed monitor shows concerning conditions at the two facilities.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Instead of helping the youth, they’ll create drama with the youth, and with each other, and they antagonize us,” said Danna Villafane, an 18-year-old who was incarcerated at Lincoln Hills twice, for a total of about three years. “It was a lot of discipline that was unnecessary, and they knew how to target kids.”

She said the staff was almost all white, working with kids who were mostly Black and Hispanic. She also said they seemed ill-equipped to handle children who had mental health issues.

“There was a couple youth that I knew there that had serious mental issues, and all they did was put their hands on them,” she said.

The monitor’s most recent report, required by a lawsuit against the state over conditions at the facilities, backs up Villafane’s experience. Guards at the facilities handcuff incarcerated youth at a rate well above the national average. Care teams, meant to deescalate situations, were also found to restrain children.

“It is an absolute atrocity that this facility will still be open past July of 2021,” said Sharlen Moore, co-founder and director of Urban Underground and Youth Justice Milwaukee.

Moore’s organizations have been pushing for changes at the state, county and city level in how to approach youth justice, citing successful efforts in states like Kansas which reallocated funding from youth prisons into community-based interventions.

“We don’t need to reinvent the wheel,” she said. “We can see what other partners across the country are doing that is proving to save money, no. 1; and no. 2, provide young people with the appropriate alternatives and innovations that they need in order to be successful.”

When a bipartisan group pushed through Act 185 in 2018, that was the goal — shift resources, and get the children at Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake back into their communities.

“Where we got stuck is how to fund and how to develop the alternatives,” said state Rep. Evan Goyke, D-Milwaukee.

Budget Woes Slow Progress

The 2018 plan required what Goyke described as a “three-legged stool” of funding: state funding for the most secure facilities; county funding to build and run community-based facilities; and juvenile mental health facilities, namely the Madison-based Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center, to handle youth diverted into treatment instead of the justice system.

The 2019 budget that followed set aside more than $100 million for counties, and funding for the Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center, but lacked money at the state-level.

“That decision, two years ago, really was the moment it was clear we were not going to meet the July 2021 deadline,” said Goyke. “You need all three of those legs working together in a continuum of care.”

Goyke and Moore both noted they’re pushing against a tide of frustration and burnout from advocates and lawmakers who put tremendous effort into the 2018 law and subsequent budget requests, only to be stymied when the necessary funding didn’t come through. However, they noted, this year has also brought new hope: COVID-19 has pushed counties to think about alternatives to incarceration — which has drastically reduced the number of children at Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake.

“They started to really analyze, what were the direct needs of that young person,” said Moore. “If COVID would not have happened, we would not be seeing this radical shift in numbers of young people going into incarcerated settings.”

The desire to keep children out of facilities, where the risk of community spread is high, has forced the justice system to leverage other resources, like intensive mental health and behavioral care within their own homes, Moore said.

“Everybody thinks that a young person has to be locked up,” she said. “But there are people that just need services … they need very intensive, wraparound services within their families. The infrastructure and the resources need to exist to have that happen.”

Keeping Youth In Their Communities

Villafane, the teen who was at Lincoln Hills twice, is from the Milwaukee area, far from the juvenile detention facility’s location 30 miles north of Wausau. That distance made it more difficult for her to see family and friends.

“It was out in the middle of nowhere, so usually the Milwaukee people, we didn’t get a lot of visits, just because we’re far — and it was a lot of Milwaukee kids, it was always a lot,” she said.

Villafane said she sometimes got calls from her father, but restrictions that only allowed family members to get on an approved call list meant friends and other adults in her life couldn’t reach her. She said some of her friends at Lincoln Hills who didn’t have relationships with their biological families felt especially isolated. On top of that, she said the facility lacked cultural understanding, and didn’t provide many spaces or opportunities for Black youth in particular.

One of the hopes for moving youth back into their communities is to eliminate the barrier of distance. Community-based facilities also tend to have a better understanding of local needs, especially when it comes to racial equity and awareness. Those are key parts of growing programs in Milwaukee County, which has redirected a lot of youth who would otherwise have been bound for Lincoln Hills.

Goyke said the population at Lincoln Hills is at 57 boys as of Friday, down from 150 when lawmakers were debating the 2018 bill, and well below the facility’s capacity of 519 children. Copper Lake has five girls, with a capacity of 29.

“One of the realities that gives me optimism is that this is a year that we can finally end this nightmare, and actually finish what we started,” he said. “With a reduced incarcerated population, the number of facilities or the size or scale of those facilities can be reduced, should be reduced, and that reduction can and should lead to cost savings, and that cost savings can or should be something that lawmakers can agree on.”

The cost per day, per youth for incarceration at Lincoln Hills was $615 as of Jan. 1, and is expected to surpass $800 by July.

For Goyke, the cost argument seems like one way to build another bipartisan coalition. Between the rising costs and the money spent on lawsuits, he said, the fiscal argument to close Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake keeps getting stronger. There’s also the argument that personalized responses to these youth, rather than a one-size-fits-all detention center, is likely to reduce recidivism, which is particularly high for those at Lincoln Hills.

“Everyone is saying the same thing, that this facility is not working for kids. The kids seem to be saying it, the staff seem to be saying it, the litigants seem to be saying it, the Department of Corrections seem to be saying it,” he said.

With growing awareness of racial injustice over the past year, especially with growing awareness of racial injustice over the past year in response to massive protests over police brutality, Goyke said fixing the youth justice system is a concrete way to work toward racial equity.

“The racial disparities in the juvenile system are rampant,” he said. “The more local control we have and the more local decision-making and the closer those kids are to our community, the more holistic and evidence-based and culturally competent decisions will be made, and connections to the community will be enhanced or at least not severed. And that results in positive outcomes.”

Milwaukee Pilots Local Solutions

Over the past five years, Milwaukee has cut the number of children sent to the central Wisconsin facilities by about 70 percent.

Brandon Weathersby, director of communications for Milwaukee County Executive David Crowley, said in an email that the county was able to put $1 million into community programs for youth who might otherwise have gone to Lincoln Hills in its last budget.

The county put that toward its Credible Messenger Program, which offers “emotional first aid, violence interruption and mediation,” and achievement centers, which help get kids into work placements, apprenticeships and other vocational services.

“These steps intentionally strive to bring those communities that have been historically excluded — or ignored — back into the fold when discussing how we create better outcomes for residents,” Weathersby said. “Getting those resources, like credible messengers or work placement services, into the right hands and into the community is key to creating positive outcomes for our residents and keeping our youth on positive and productive path.”

Weathersby said the county needs more funding to keep going. The gap between what the county takes in and what it needs to spend is growing, which he attributes to state-imposed funding limits and the growing cost of state-mandated services. Milwaukee County is looking at a local solution, raising the sales tax by 1 percent, he said, which would help fund the existing programs, develop new programs for youth, and fund other local priorities.

Moore said Milwaukee County’s successes point to a shortcoming in the 2018 plan: its funding allocations were for the facilities themselves — the brick-and-mortar buildings — rather than for the programs to keep kids closer to home and out of the carceral system.

“The framework is already there, we just need the right leadership in the state in order to say, ‘You know what, we care about these young people, and we’re willing to do something that’s going to make an impact on their lives,’” she said. “We should be doing what’s best for every single child in this state, and that’s an issue that we can’t play politics with.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated to clarify that former Gov. Scott Walker’s deadline for closing Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake youth prisons was January 2021. Gov. Tony Evers pushed that deadline in 2019 to July 2021.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.