Normally, the summer is a time for local health departments to capture, count and test for bugs like ticks and mosquitoes.

In 2018, over 3,000 people in the state contracted Lyme disease from blacklegged ticks found on deer. Susan Paskewitz, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of entomology, said that number just represents known and suspected cases, and is only the tip of the iceberg.

“That’s likely to be an underreporting by a factor of ten. So, it could be as many as 30,000 of our citizens are getting infected,” said Paskewitz.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

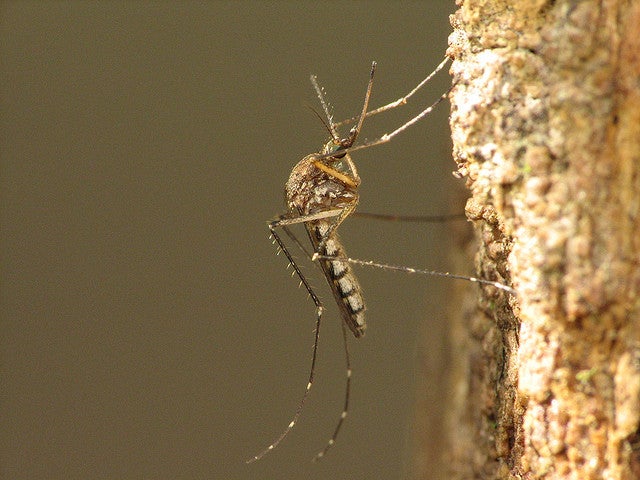

And then there are mosquitoes, which can carry West Nile virus and other diseases that they spread to humans while they feast. There were 33 cases reported West Nile cases in 2018.

But this summer, the attention of health departments across Wisconsin is focused squarely on the coronavirus pandemic — taking scarce public health dollars and time away from other, more routine health threats. That includes tick and mosquito surveillance.

“This year all of our public health staff is operating on an ‘essential services only’ basis,” said Maegan Jacob, an environmental health specialist for Walworth County.

Funding Also A Barrier For Tick, Mosquito Surveillance

Concerned that coronavirus may be prompting other health hazards to go undetected, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have urged local health officials to continue mosquito surveillance.

But even before the coronavirus pandemic hit, Wisconsin had planned a reduction in mosquito surveillance this year. Such disease-monitoring programs rely heavily on federal dollars.

“Public health is a victim of boom and bust cycles where there might be a large outbreak — most recently it was Zika virus in 2016 — that provided us with additional federal funding,” said Rebecca Osborn, a vectorborne disease epidemiologist at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. “Unfortunately a lot of that funding isn’t permanent. This is a very common phenomenon. I’m sure we’ll see it with coronavirus to some degree. So, as funding fluctuates we have to adjust our program accordingly.”

For most people, mosquitoes are merely annoying. But researchers know the threat they pose to humans.

“If nobody’s out there surveying, these things can really creep up on you quickly. So it would be possible that if we had the right kind of conditions, we’d have outbreaks of West Nile virus and be totally unprepared. I mean we would not know. We wouldn’t receive the signal that we usually get when we were looking at infected mosquito pools,” Osborn explained.

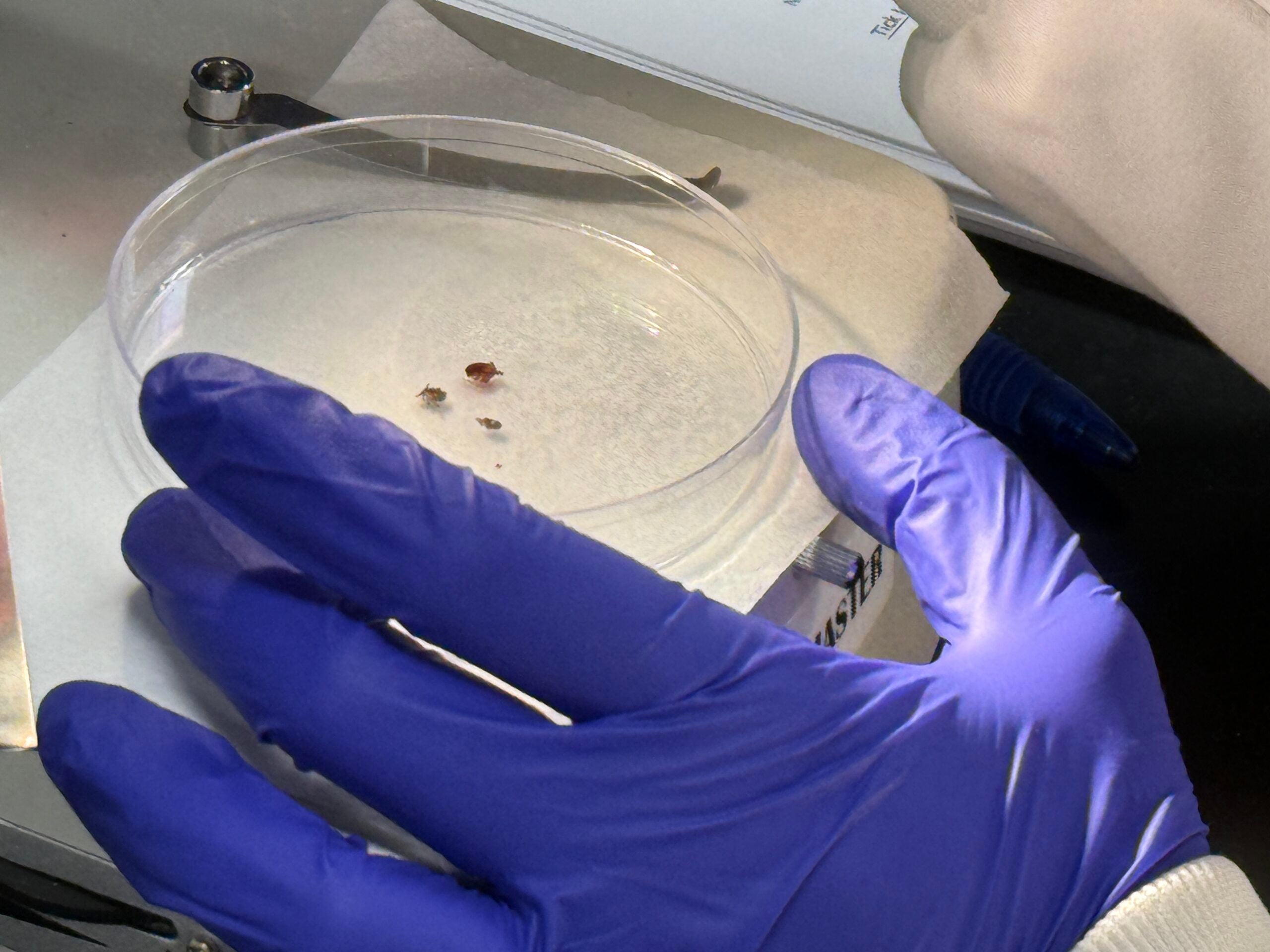

Paskewitz directs the Midwest Center of Excellence for Vector-Borne Diseases, which has continued to search for ticks, but not mosquitoes, in state parks this year. Only three state parks — Tower Hill near Spring Green, Council Grounds in Merrill and Hartman Creek near Waupaca — have been checked for ticks. Normally there would be surveillance in 10 or more state parks, in addition to local hotspots.

The Hunt Continues

In July, Paskewitz hunted for ticks in a marshy, shaded part of the UW Arboretum known as the Lost City. It’s a housing project from the early 1900s that was never completed — the first homes sunk into the bog around them.

Paskewitz used a heavy piece of canvass with fringes on the end to capture the bugs. The tool is dragged on the ground in the hope ticks will try to hitch a ride.

“Anything moving by, they’re going to grab it,” said Paskewitz. “And then they can make a choice if it’s not the right thing. Unless it’s cold, this works really well to pick them up.”

The Arboretum, she said, is a “low-intensity” site compared to other places in Wisconsin where ticks are more abundant. It’s that prevalence statewide that has health officials cautioning people to be careful as they go outdoors, and if bitten to go to a doctor.

But in Wisconsin and across the country, people have put off health care in part over concerns about catching COVID-19.

“Folks are more hesitant potentially to go in and see their providers to get checked out if they have headaches or fever. Things like muscle, joint aches and fatigue. They may be more willing to dismiss those symptoms instead of going and getting checked out and get tested,” said Ryan Wozniak, who supervises vector-borne diseases within Bureau of Communicable Diseases at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

Wisconsin continues to track how many people get sick from tick and mosquito infections. But if people ignore symptoms, reported cases could be lower than they actually are during a time more people are going outdoors in hopes of bolstering both mental and physical health.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.