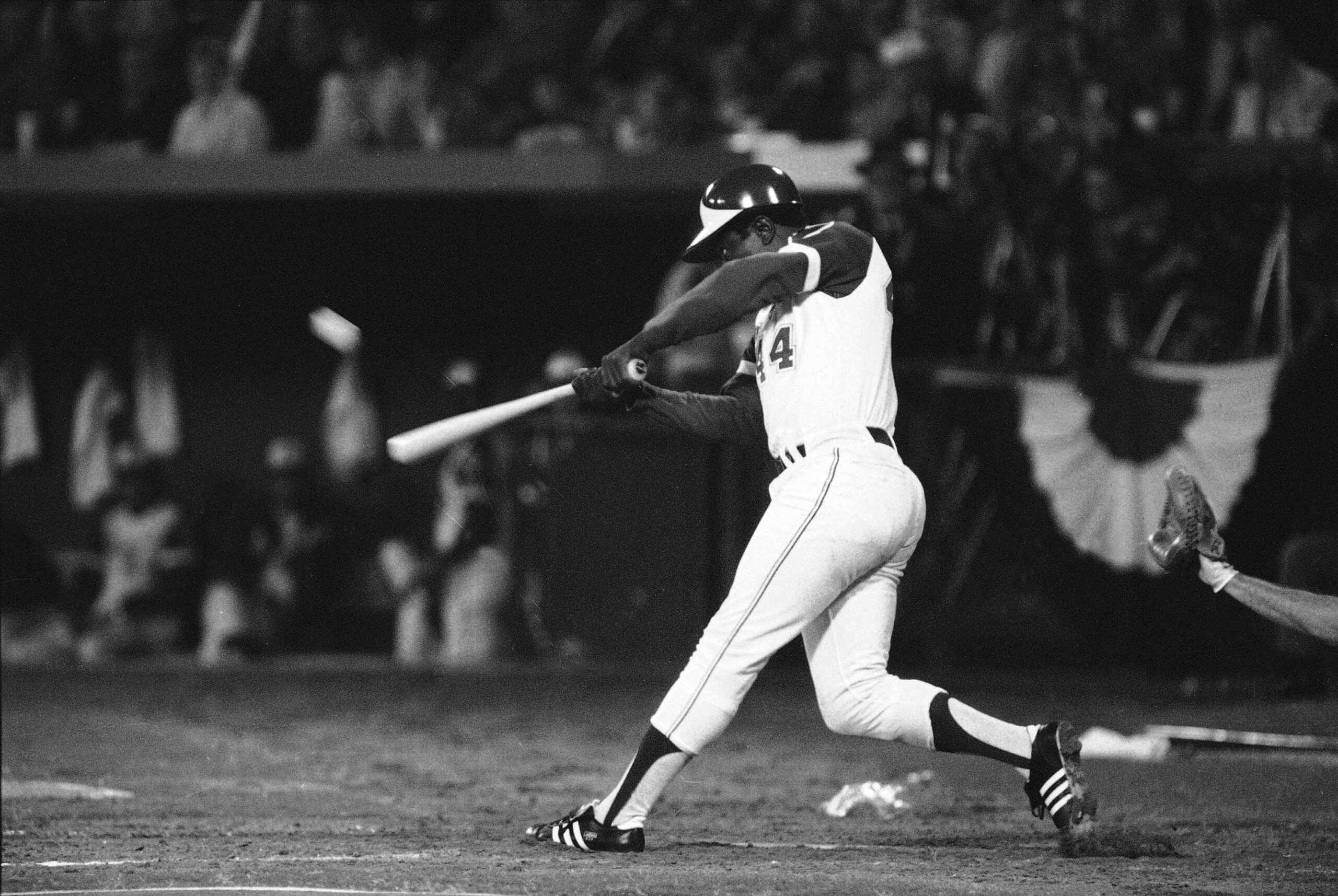

The chase to break Babe Ruth’s 33-year-old record for career home runs took a toll on Hank Aaron.

By the time Aaron hit his 715th homer in 1973 to secure the title of “home run king,” he had been subjected to more racial hate mail and death threats than he cared to admit.

“He looked at that time period as something that affected him for the rest of his life,” said Terence Moore, author of a new biography about Aaron, during a recent interview with Wisconsin Public Radio’s “The Morning Show” with Shereen Siewert.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

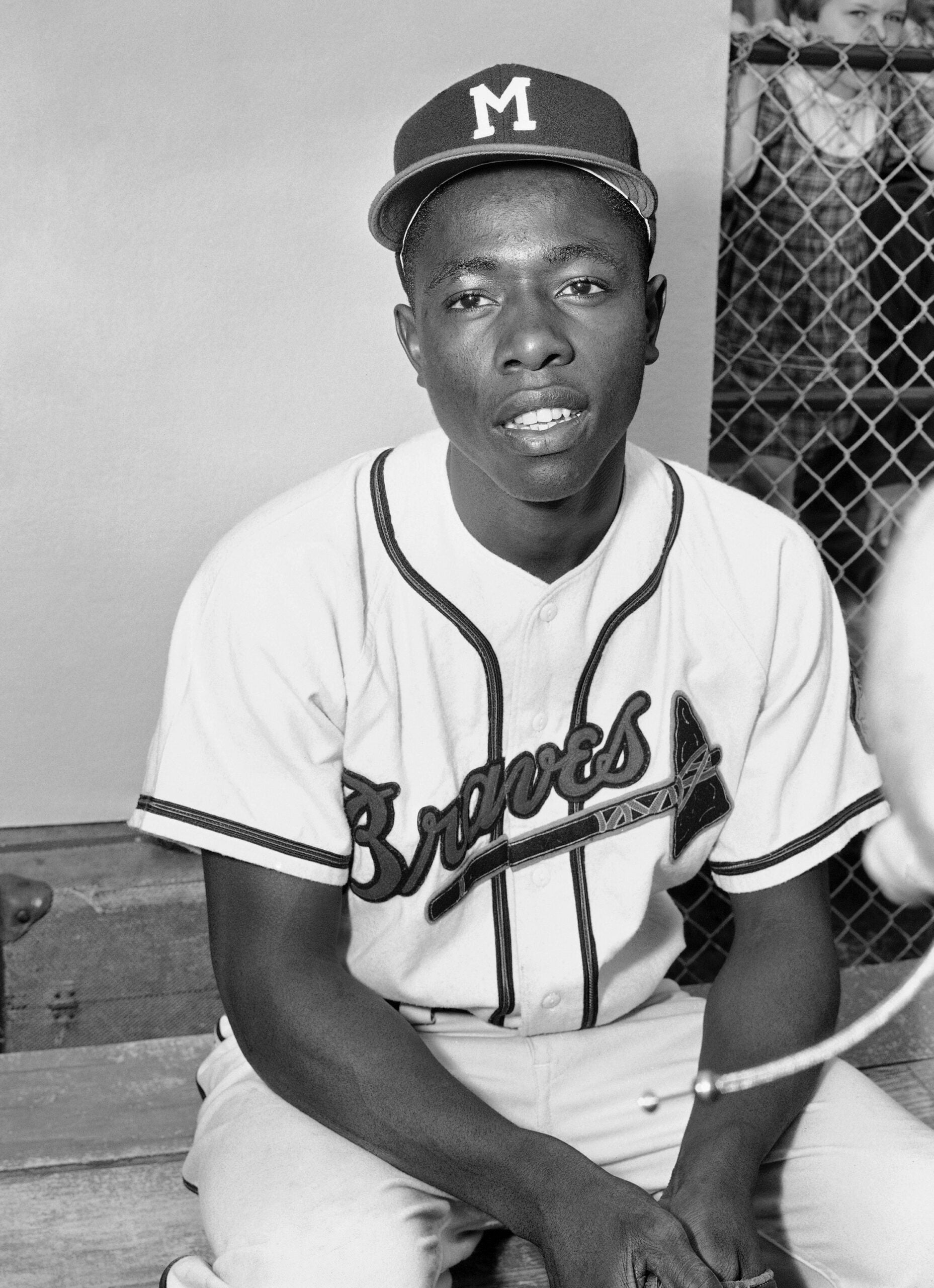

Aaron started and ended his professional baseball career in Milwaukee, debuting with the Braves in 1954 and retiring with the Brewers in 1976. He would eventually notch 755 career homers. Last year, Aaron died at age 86.

Barry Bonds broke Aaron’s home run record in 2007 while facing allegations of using performance-enhancing steroids. Aaron steered clear of commenting publicly on Bonds’ accomplishment. But Moore said Aaron confided in him.

“Hank told me many times during that period that until and unless Bonds confessed that he used steroids on purpose to hit home runs or to just be a great player in general, Hank Aaron was willing to give Bonds the benefit of the doubt,” Moore said.

During “The Morning Show” interview, Moore discussed Aaron’s place in history, his final years playing in Milwaukee, his friendship with Moore and other details from his life. Moore’s biography of Aaron is titled, “The Real Hank Aaron: An Intimate Look at the Life and Legacy of the Home Run King.”

The interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

Shereen Siewert: Talk a little bit about that friendship. How did it develop over the years? How did you get so close?

Terence Moore: It essentially started in 1982 when I worked for the San Francisco Examiner.

I did this detailed study of what was happening to African Americans in baseball. I discovered there was a steady drop of African American players from its peak in the mid-1970s of 25 percent, down to 19 percent in 1982. It’s below 10 percent now. And the general consensus among the people I talked to — players, coaches and administrators, white and Black and on the record — was Major League Baseball had a quota system and was phasing out African Americans.

In 1982, Hank Aaron was the only African American in a front office (of a Major League Baseball Team, the Atlanta Braves) at the time. I called him up (for comment). We clicked from day one.

SS: Was Hank Aaron the greatest baseball player of all time?

TM: Oh, clearly. Granted, I’m biased, but I can make a case for this. The only people who are in contention for the greatest player of all time are Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron and Willie Mays.

Babe Ruth is out of the picture because anything prior to April 15, 1947, when Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, doesn’t count.

That means that Babe Ruth didn’t play the best available competition. He was just playing against white players.

Then you come down to Hank Aaron and Willie Mays. Hank Aaron beats Willie Mays in just about every single offensive category: home runs, batting average and running down the lines.

READ MORE: Hank Aaron, Baseball Slugger With Close Ties To Milwaukee, Dies At 86

READ MORE: Baseball Legend Hank Aaron’s Early Career In Eau Claire

SS: When Hank Aaron was pursuing Babe Ruth’s career home run record, he faced significant challenges. Baseball fans sent hate mail to him. He received death threats. How did he handle that kind of reaction?

TM: People did not understand that there were days when he could have starved, because he couldn’t leave his hotel room to go out to get a bite to eat. His teammates had to bring food to him, because it was so terrifying to leave the hotel room (out of fear) that something bad might happen.

In our last interview in the fall of 2020, he said he basically resented the fact that white superstars, such as Pete Rose, Cal Ripken Jr. and Mark McGwire, could chase these historic Major League Baseball records and, in his words, go basically unmolested along the way. Whereas Hank Aaron, in the early ’70s when he was chasing Babe Ruth, went through what he said was just holy hell.

Hank Aaron was eternally haunted by that Babe Ruth (career home run) chase and what he had to go through. The death threats, the hate mail. That’s in large part the reason why he refused to comment on that entire race by Barry Bonds.

SS: Do you think the career home run record is still Hank Aaron’s?

TM: No doubt about it. He is the legitimate home run king.

SS: Hank Aaron nearly retired before requesting a transfer to finish his career in Milwaukee. And he was close to being traded to the Boston Red Sox. Tell us about that.

TM: In 1974, after breaking Babe Ruth’s record in Atlanta at Falcons Stadium against the Dodgers, Hank told me that he wanted to retire right then. He said he was done. He was mostly spent. He wanted to end the ’74 season with the Braves and retire. But he said negotiations broke down, because the Braves did not give him what he wanted — a front office position. They wanted him to be more of a figurehead. And he didn’t want that.

I said everybody assumed that the Brewers were the only team that Hank could go to or was thinking about going to. But he said he also had an opportunity to go to the Boston Red Sox. Just think about that, Hank Aaron ending his career in Fenway Park.

But he said that one of the greatest things that happened to him was finishing his career with the Brewers. I think people can understand, given his love affair with Wisconsin and Milwaukee.

SS: What do you want people to know about Hank Aaron’s legacy, what he meant to you?

TM: Quite simply, he was more than 755 home runs. He was an everyman. He was funny. He cared about humanity and he really, really cared about the state of Black America and youth. But the final thing I would say about Hank was he was the guy next door. He was the guy you wanted as your neighbor.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.