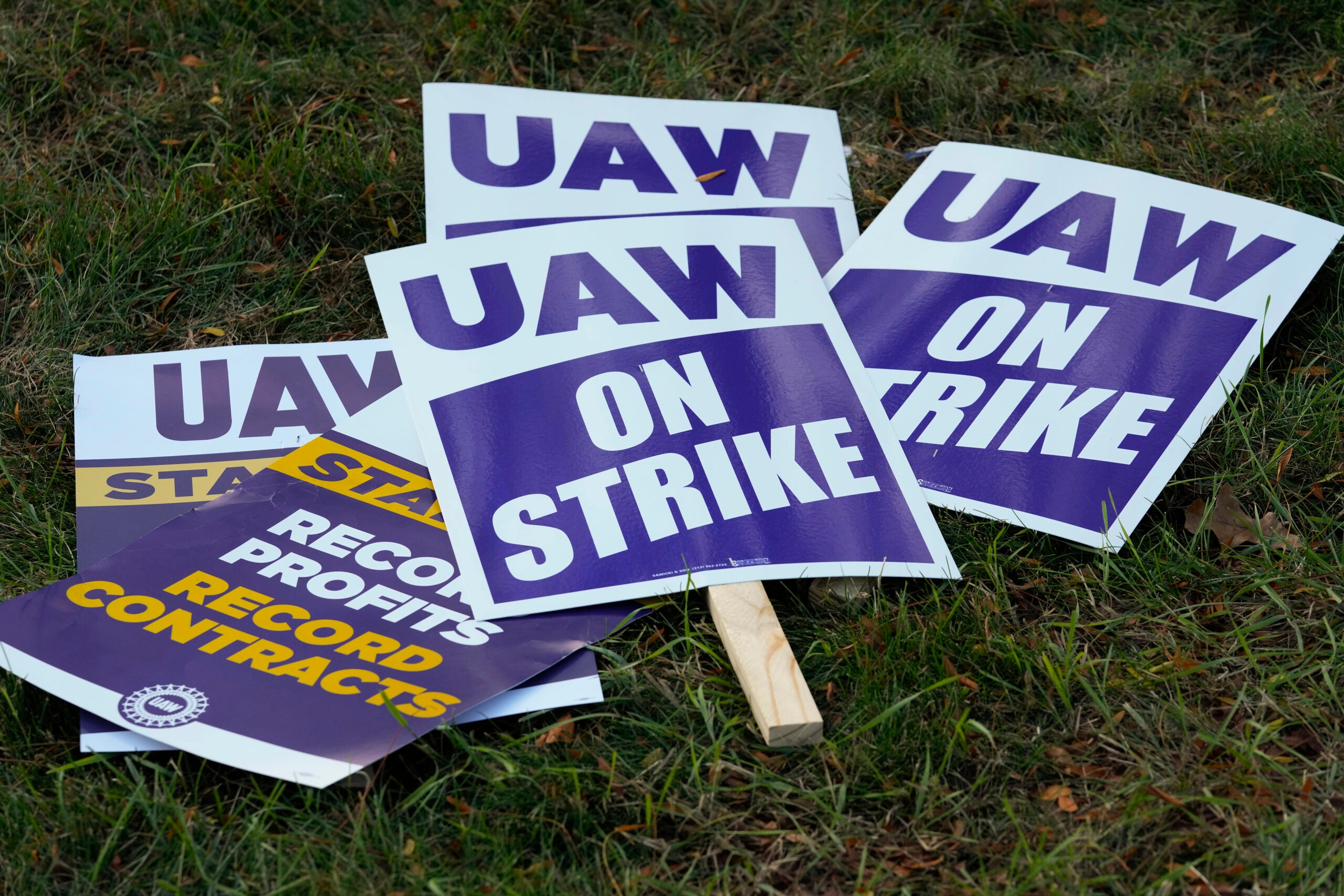

After almost nine months on strike, and following threats of being replaced, the union representing more than 1,000 Case tractor factory workers in Wisconsin and Iowa agreed to a new contract with the company Saturday.

United Auto Workers Local 180 represents about 700 employees at Racine’s CNH Industrial, which produces agriculture equipment. They have been on strike since last May, along with UAW Local 807 members at CNHi’s Burlington, Iowa plant.

Employees approved a new contract Saturday after a mediation session conducted by U.S. Labor Secretary Martin Walsh.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The new agreement comes after the company threatened to permanently replace the workers on strike and amid union membership declines in Wisconsin.

CNHi and UAW International have not released the specifics of the new deal. The two sides were in disagreement over pay and benefits, and the company’s previous “last, best and final offer” was rejected by the union about two weeks ago.

‘The scare tactic worked’

While a new deal was ultimately approved, it wasn’t a unanimous decision.

The majority of members of UAW Local 180 in Racine voted against the new contract, but they were outvoted by members of UAW Local 807 in Iowa who voted to ratify the deal, according to Rich Glowacki, chairman of UAW Local 180’s bargaining committee. He said the agreement was the result of pressure from the company.

“They sent letters to our members informing them that they were going to start permanently replacing them,” Glowacki said. “If someone holds a knife to your throat and threatens you with your job, that tends to make people think about things in a different light.”

That pressure helped turn union members’ votes, he said.

“The scare tactic worked, especially in Burlington,” Glowacki said. “Racine did not approve it.”

In a statement, CNHi Chief Executive Officer Scott Wine thanked the company’s bargaining team, UAW leadership and Secretary Walsh for helping “navigate the complexities of the negotiation process” to end the months-long strike.

“We look forward to welcoming our employees back to work, building the machines that help our customers feed the world and build its essential infrastructure,” he wrote.

Although few details of the new contract have been released, CNHi said it is fair to employees and “provides a framework for the company to better serve” its customers. Meanwhile, UAW International says the deal provides wage increases, shift premium increases, classification upgrades and other improvements.

“This agreement reflects the effort of a determined bargaining team and members being on an almost nine-month strike,” UAW President Ray Curry said in a statement.

New contract fails to meet UAW Local 180’s demands

While the company and UAW International have framed the new contract as a win, Glowacki said it doesn’t feel that way for many in Racine.

He said some of the things union members were fighting against, including a tiered health care package, made it into the deal. The new agreement increases employee pay, but Glowacki said it leaves Racine’s CNHi employees underpaid compared to other area manufacturers.

“You could go work at the HARIBO gummy plant (and) make $26.85 an hour, but you won’t make that making a $500,000 tractor,” he said.

The new deal could lead many of CNHi’s Racine employees to look for work elsewhere, Glowacki said, noting many already found new jobs during the strike.

“We feel that we are not being appreciated and that our skill sets that we bring to the table are not being compensated for correctly,” he said. “And thus in return, the company is going to see how many of our people who choose to come back. And, from what I’m hearing, it’s not going to be many.”

Past concessions, labor shortage may have extended the strike

This isn’t the first time CNHi employees have ended a strike without getting all they hoped for. In 2004, CHNi workers in Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois and Minnesota called a strike after negotiations broke down.

When workers voted to end the strike after 19 days, the company locked union employees out for another 17 weeks. In the end, workers accepted a contract that included concessions.

Prior givebacks, coupled with a labor shortage and effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, may have made employees more motivated to strike for better treatment this time around, according to Steven Deller, professor of agricultural and applied economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“If I was a union member, and I’d been giving up concessions for years and years and years, and I was looking at the labor market right now, I would be saying, ‘Hey, can we make up some of those concessions that we gave up years ago?’” Deller said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.