When Ingrid Walker-Henry was a student at Milwaukee Public Schools, she remembers the Black history in her textbooks as being incredibly limited — maybe two columns in a history textbook with a picture of a slave auction and some explanatory text.

“That was my experience of Black people if my teachers had just stuck to what was in a textbook,” she said. “I can’t imagine looking at students in my classroom — looking at Black students, looking at Latino students, looking at Asian students, and not pulling in stuff that is relevant to them.”

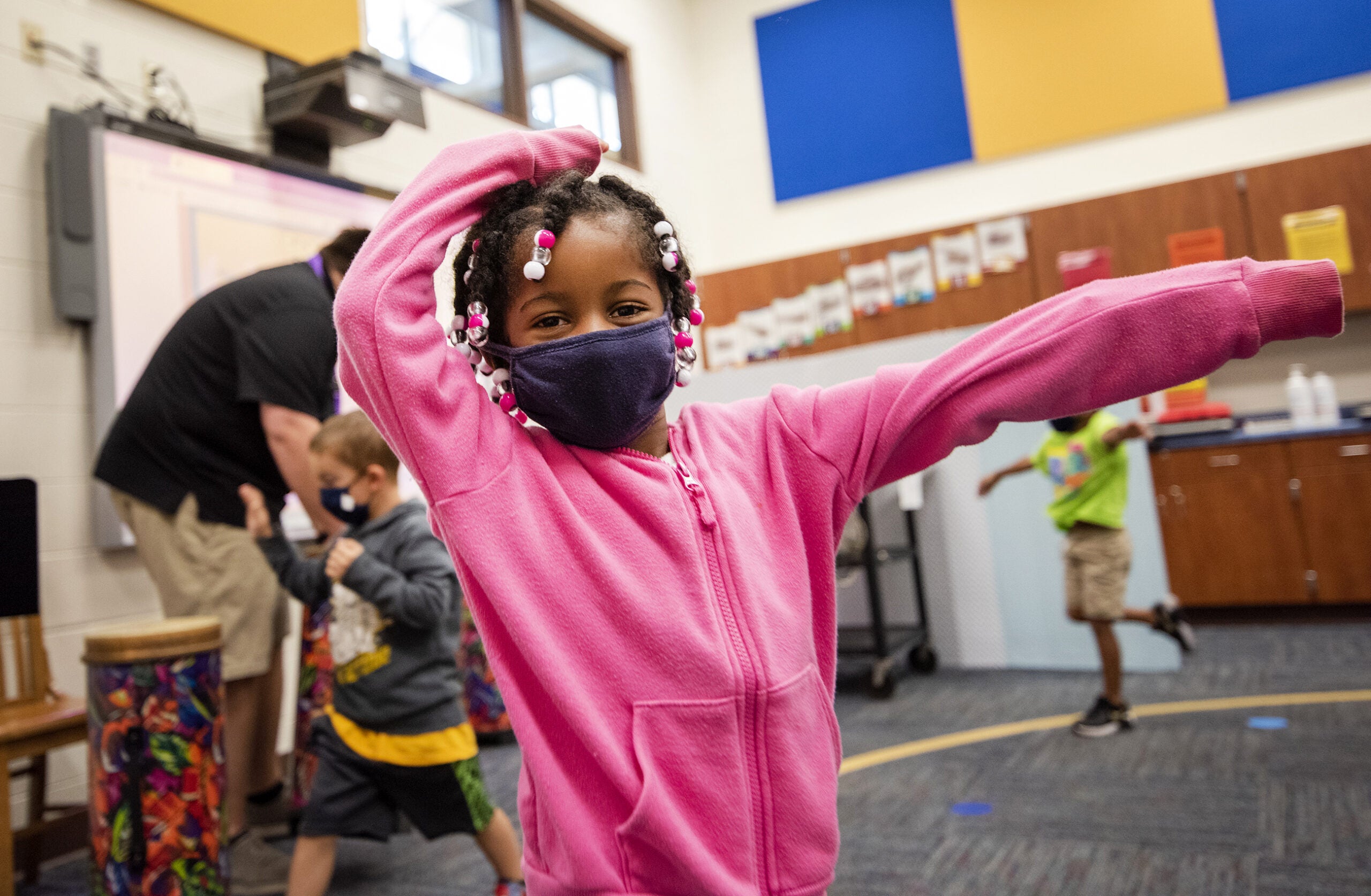

Walker-Henry, a teacher and vice president of the Milwaukee Teachers Education Association, now gets to help shape those more inclusive history lessons for current MPS students. The district teaches about Black history through art and has lessons focused on Black disability rights activists and Black educators in the Civil Rights Movement. For the last several years, MPS has participated in Black Lives Matter Week of Action, a week of programming on Black history and culture that’s designed to engage the larger school community as well as students.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Walker-Henry said the conversation about how to hold the annual Week of Action events looked a little bit different because of COVID-19 precautions, but it wasn’t affected by another issue that’s been bubbling over in Wisconsin during the pandemic: pushback against the way schools and teachers talk about race.

In Wisconsin and around the country, some teachers and school districts who have tried to bring conversations about racial justice, equity and history into the classroom have gotten strong pushback from often small but very vocal groups of parents who call it “critical race theory.” In Burlington, a teacher who talked to her students about Black Lives Matter after the police shooting of Jacob Blake in 2020 kicked off heated debates in the community about how to discuss racism and activism. In Elmbrook, a plan to adopt “equity principles” to guide the district’s policies created uproar. Around the country, state-level bans on teaching so-called critical race theory have left teachers wondering if they could move forward with their usual Black History Month lessons.

When Meg Fisher started planning for the return of the Kenosha Unified School District’s Black History Bee, a 19-year tradition that was on hiatus last year because of the pandemic, she was more concerned about pushback.

“For the first 18 years of doing this, I’ve never had any concern, really. I get the occasional, ‘When is White History Month?’ and on occasion I get some stuff that’s a little snarky,” she said. “When I decided I wanted to do it again this year, it was with a completely different feeling. I was hesitant — there was definitely fear of how somebody might twist and turn this.”

The bee traditionally consists of each Kenosha grade school holding a separate quiz contest for fourth and fifth graders to answer questions about Black history, with the winners going on to a district-wide competition. Fisher writes the questions herself, drawing on national history as well as Wisconsin-specific Black history. Some questions are consistent, and others rotate in and out, or are more permanently phased out and added in — an early bee question on Bill Cosby, for example, is no longer on the list.

This year, Fisher went to the district’s administration to ask for people to check her work and serve as a kind of oversight committee, so she’d have people in her corner if the bee draws more ire this year.

“I think part of what will help me is that we’ve been doing this for 19 years,” she said. “We’ve never had an issue, never had a problem with what’s been taught or how it’s being taught.”

The idea for the bee came to Fisher when she started noticing gaps in her own knowledge about Black history as an adult. She wanted to make sure her students learned more than she did. In particular, she likes to incorporate local and state history. She’s included questions on the first Black family to live in Kenosha, Underground Railroad stops around the city’s Library Square, Kenosha native and current NFL player Melvin Gordon and Olympian Jesse Owens’ visit to Kenosha to race against a Harley-Davidson motorcycle.

“There’s just so much more that we could and should be doing to make this a more inclusive state,” she said. “So, we’re trying.”

Peggy Wirtz-Olsen, president of the state’s largest teacher’s union, said her members haven’t reported any issues with district or community pushback over Black History Month lessons so far this year.

“We stand with our educators in teaching true history. We stand with our educators in helping students understand the roots of inequality and giving them the tools to shape a just future,” she said. “We’ve been clear that when those kinds of challenges occur, they reach out to ensure that they have our support, which they unilaterally do.”

Walker-Henry, the MPS teacher, said she loves to see students get excited about not only Black History Month, but about lessons year-round that reflect their own communities and history. Last year, one month her students learned about Juneteenth, which she said they loved. Students learned the history and designed their own commemorative coins for the holiday.

“We’re always trying to do things as a teacher that interest students and really hit at their different skills and talents,” she said. “It’s about really making those connections to things that interest them and, I would say, also the community.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.