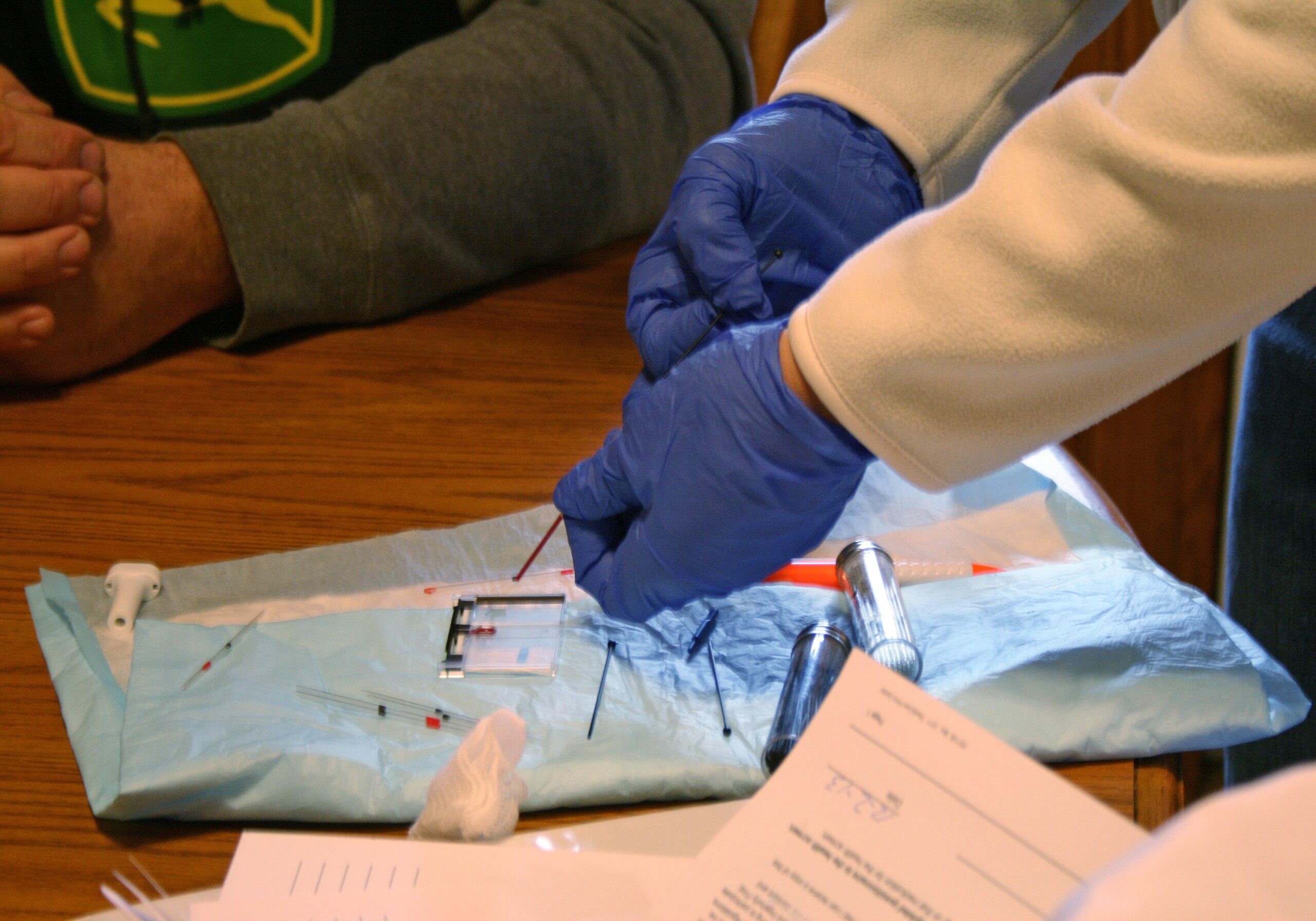

Even before the pandemic, nurses were in short supply due to an aging and increasing patient population. Now, burnout aggravated by the pandemic is increasing concern about even more people either leaving, or entirely avoiding, the profession.

Prior to the coronavirus, Wisconsin needed at least 3,000 more registered nurses, according to Gina Dennik-Champion, executive director of the Wisconsin Nurses Association. Nationally, the country will need to fill nearly 176,000 registered nurse positions each year through the year 2029, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“We all saw when the surge really hit Wisconsin and our Wisconsin workplaces, that we did not have enough nurses,” Dennik-Champion, a registered nurse, said of the upswing of coronavirus cases that hit the state in the fall. “Those nurses were probably running on adrenaline, but after a while the adrenaline starts to leave, you can’t keep up with that level of energy.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“What we’re seeing now is the impact of that,” she continued. “The nurses are very fatigued, feeling very challenged.”

The critical shortage of nursing staff felt during the pandemic could be a taste of what’s to come, she said.

“The shortage itself shows what I’m thinking we could be experiencing in the very near future if we don’t pay attention to what we need in the future,” she said.

A national survey by NurseGrid released in January found a dramatic rise in nurses expressing concerns about burnout and their mental health. More than 60 percent said they were most concerned about burnout in December 2020, compared to only 25 percent in April.

“Pre-covid … nurses were feeling it,” Dennik-Champion said. “This certainly came as a blow. COVID was something new and really required whatever nurses could do to help, And they just rose to the occasion, as nurses do. But the burnout is real and … they’re exhausted.”

“We need to increase the supply of our nurses,” she continued.

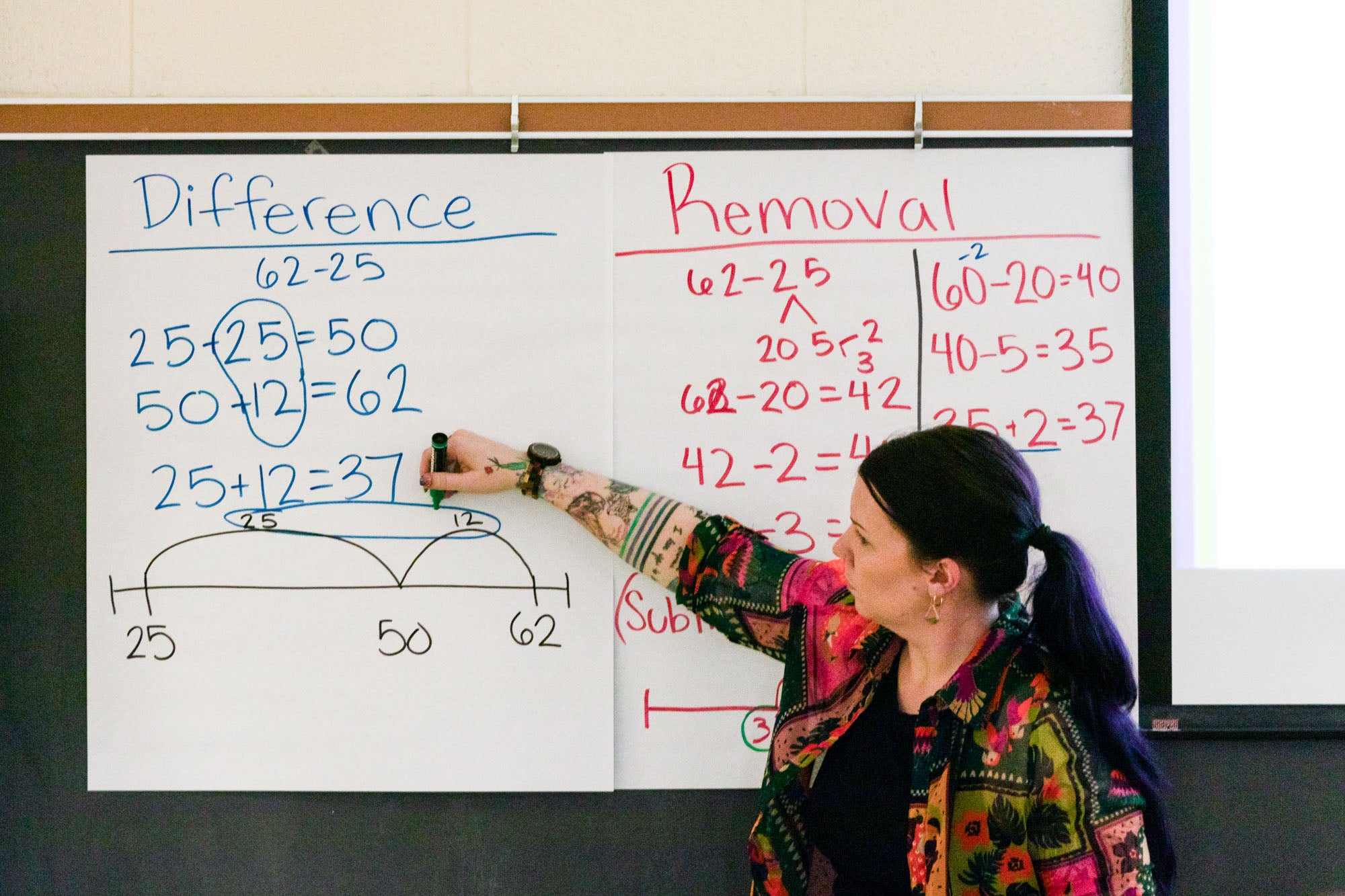

Making the shortage of nurses notably worse is the critical shortage of faculty to train those who want to pursue nursing.

Linda Young, dean of the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire’s nursing college, calls the lack of nursing faculty the bottleneck of the larger issue. In 2018, the UW System had to turn away more than 500 qualified students from its nursing programs around the state because of the lack of capacity.

“We don’t have enough faculty to open that up so that there can be that greater number of nursing graduates moving into the health care industry,” she said.

It’s a problem that has been brewing for over a decade, and continues to worsen, Young said.

A major part of the issue is that salaries in the health care system are much higher than in education. And recently, two of the major health care systems in Wisconsin made a significant salary increase for all employees, she said.

“And what that means to me as a dean of a nursing school is I’m even less competitive now … compared to nurses who are working in health care,” Young said. “It’s going to be another challenge to retain my faculty when the draw for earning so much more is just across the street.”

Then there are the retirements, which Young said they’re unable to keep up with. According to the 2020 RN Workforce Report, in less than a decade, the state will see a 58 percent reduction in nurse faculty.

“We have not been able to replace the 112 vacancies that exist right now in Wisconsin, so you can see how compounding this is,” she said. “I have three positions that I have been advertising for three years that have gone unfilled … we’re lucky if we get two qualified candidates.”

The pandemic has had the same effect on nursing faculty as the profession as a whole — speeding up retirements and high levels of burnout. Yet at the same time nursing programs are experiencing what Young calls “the Fauci effect.” Applications to nursing programs are up 4 percent, and they’re projected to continue to rise, she said.

While Young said she’s happy to see more students want to join the profession, it doesn’t change the harsh reality that many will be turned away because she won’t have enough faculty to teach them.

“I want people to know that this will impact the health care they’re receiving,” she said.

The Wisconsin Nurses Association and Administers of Nursing Education of Wisconsin are requesting $10 million in state funding to address the issue. The program would offer student loan forgiveness in exchange for a three-year commitment to teach in a Wisconsin nursing program.

Young said they’re aiming to bring about 250 nursing faculty to the state.

“That’s not going to resolve the issue in the next nine years, but it will help, and then we will have time to look at something that is more sustaining,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.