Artist Mary Gill is still learning how deeply rooted racism is in America.

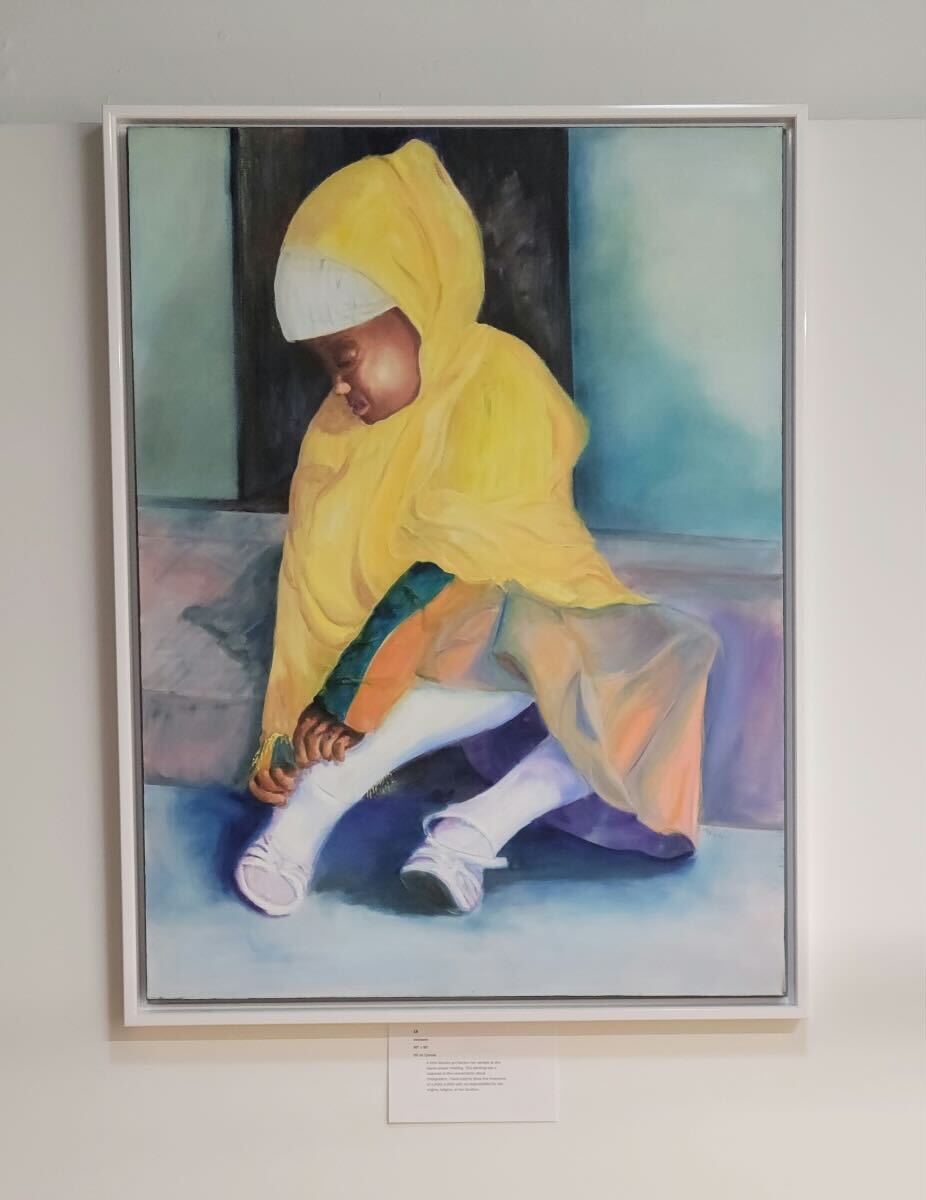

She immigrated to the United States from Trinidad and Tobago decades ago. Her art reflects her heritage — paintings that depict ordinary scenes of Black people.

“Being a foreigner in a country that was foreign to me, I personalized it. I said, ‘Maybe something’s wrong with me,’” she said. “And it’s only many years later, I’m beginning to realize that it’s not just me.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Gill was one of about 200 people to attend a panel called “Black Women Artists Speak” at Madison College’s Goodman South campus Tuesday night. The event came after a string of incidents — in which an artist was harassed and her work was vandalized — prompted calls for change at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, or MMoCA.

“People say my work is beautiful. How come it’s not accepted in the galleries?” Gill said. “I am in my 70s now, and it’s a fight I don’t want to fight anymore.”

It’s not just galleries that have rejected her work. Gill said people have told her they don’t know where to hang her paintings in their homes. Others have said it’s too expensive.

It got Gill thinking: does she charge too much for her work? But in June, she took a lap around the state Capitol’s “Art Fair on the Square” to compare prices. White artists, she said, were charging the same for their work.

“The work that I have sold in Madison is all fruits and flowers, when in fact, what I paint are Black people,” she said, adding, “because of the Blackness, it’s not accepted.”

These collective experiences drove Gill to attend the panel sponsored by the Madison Arts Commission, Friends of the Madison Arts Commission and nonprofit Seein is Believin. The event was intended to create space for Black women artists in Madison after a series of events called MMoCA’s treatment of artists of color into question.

Black artists say MMoCA ‘ill-equipped’ to support them

In April 2021, MMoCA announced its Wisconsin Triennial event, “a celebration of the breadth and range of artistic practices in the state.”

This year’s exhibit, “Ain’t I A Woman?” highlights the works of Black women and nonbinary artists. In March, Madison artist Lilada Gee was working on her contribution to the exhibit. She said she stepped outside to grab supplies from her car. Gee called Annik Dupaty, MMoCA’s director of events and volunteers, to let her back into the building. A white employee of the Overture Center, where the museum is located, verbally attacked and physically intimidated her, as first reported by Madison365. The employee was later fired, and their identity has not been disclosed.

Gee wrote an open letter about her experience and left a blank canvas on display.

In June, a woman and her children defaced and stole Gee’s art — saying they thought the piece was interactive. Shortly thereafter, MMoCA’s Director Christina Brungardt called Gee to inform her of the incident and asked if the family could keep the artwork they had vandalized. The museum later put out a statement in August apologizing for the damage to the artwork and the pain it caused.

“The damage to Lilada Gee’s artwork inside the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art (MMoCA) is unacceptable,” the statement read. “Lilada is a talented artist and an invaluable voice for Black women and girls. We were proud to have her and her artwork as a part of the exhibit.”

Some community members have called on Brungardt to resign. The museum has rejected charges of institutional racism.

Amid calls for change, at least 10 of the 23 artists involved in the Triennial have pulled out of the exhibit. Several of the artists have signed an open letter, saying the museum was “ill-equipped” to take on the project.

Black artists call for visibility, representation

Gee said these incidents have prompted important conversations. But they’ve also hammered home the realities of working as a Black woman artist as they fight for more creative, economic and artistic opportunities.

“When we talk about equity and art, it’s not just wall space. It’s every other opportunity that goes along with the American Dream that Black artists are left out of,” Gee said.

While Gee noted there have been more opportunities in Madison in recent years, she said there’s more work to be done.

“We have to first acknowledge where we have fallen short as a community. And what’s been the impact of that?” she said. “If we can’t even admit that there’s a problem, there is no hope for change.”

Catrina Sparkman is a best-selling author, publisher and the founder of “Creator’s Cottage,” an art maker’s space that serves women of color.

She said conversations about making Madison a more inclusive space for artists of color needs to happen outside of controversial events.

“I would like to see more dialogue come with less emotional baggage attached to it,” she said. “You don’t have to wait til something horrible happens.”

Sparkman said she’s been told to go to bigger cities like Chicago or New York, but moving isn’t always an option. She noted that publishers typically pay low wages, making it difficult to afford to live and create in those places.

Gill said she’s looking for wider markets in those big cities herself, saying, “I think that’s the only way I would be able to survive if I want to continue being an artist.”

One gallery artist said her work is “too specific,” her portraits wouldn’t resonate with people. Yet people outside of Madison, Gill said, are taking an interest in her art.

For her, creating something that speaks to her lived experience is more important than selling paintings. But she and other Black women artists in Madison hope the city becomes a place that accepts and empowers artists of color.

“I will continue to paint what I want, what touches my heart,” Gill said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.