A bipartisan bill is expected to be released this month that would change the way most public schools in Wisconsin teach reading.

State Rep. Joel Kitchens, R-Sturgeon Bay, who chairs the Assembly Committee on Education, has been working with the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction on the plan that would move more schools away from teaching what is known as “balanced literacy,” to a “science of reading” approach.

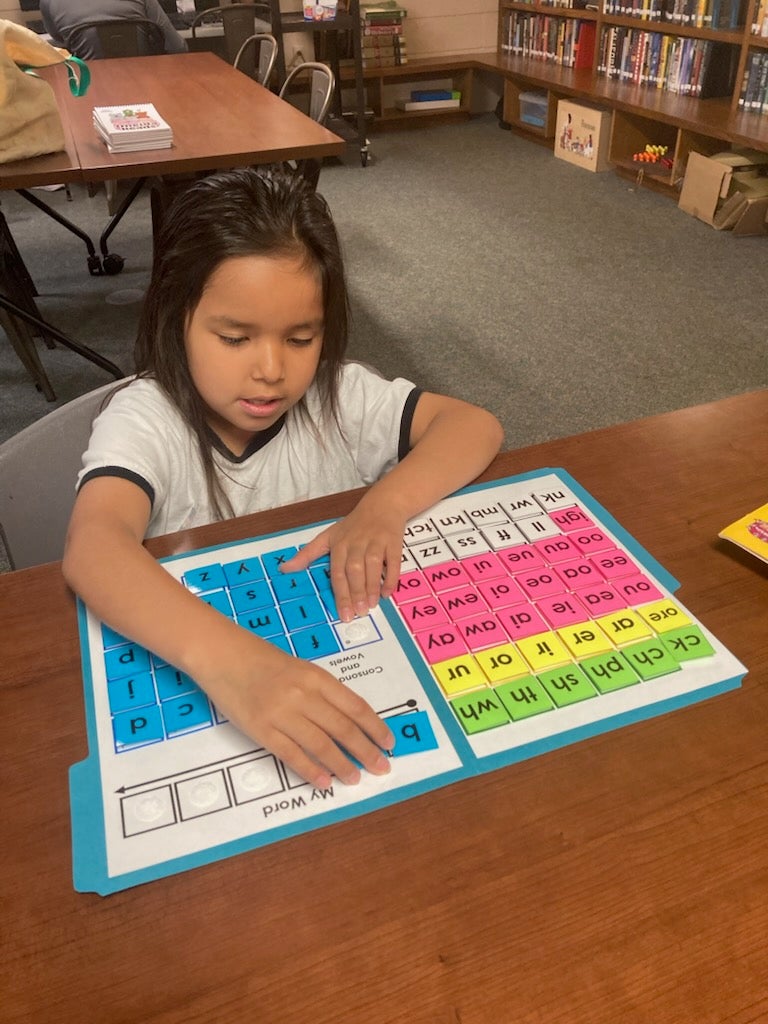

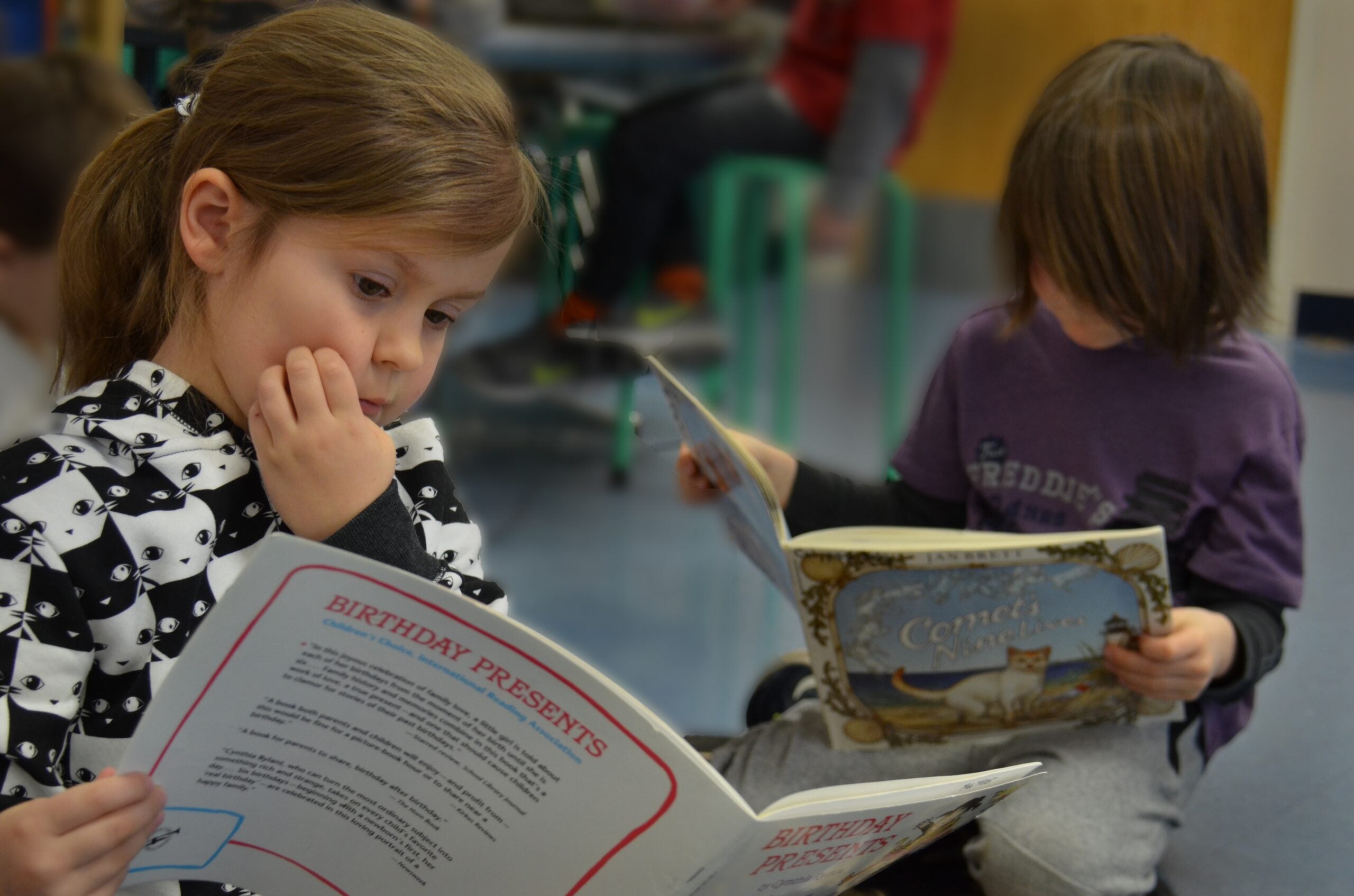

Instead of being taught reading through pictures, word cues and memorization, children would be taught using a phonics-based method that focuses on learning to sound out letters and phrases.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

According to DPI, only about 20 percent of school districts are using a phonics-based approach to literacy education. Other reading curriculums that don’t include phonics have been shown to be less effective for students.

The bill will be introduced separately from the 2023-25 biennial budget that is currently being crafted but $15 million to support the plan would be included in the budget, Kitchens said during an April 24 interview on Wisconsin Eye.

“Education is the one chance we have to break the cycle of generational poverty that we see in Wisconsin and reading is by far the most important skill to allow children to be successful in school,” Kitchens said.

Kitchens told Wisconsin Public Radio on Thursday he is updating the current draft of the bill and will share it with DPI “in coming days.”

“Hopefully it will be out within the next two weeks,” Kitchens said.

The $15 million would purchase new reading curriculum and would hire 52 teaching coaches. The coaches would be divided between low-performing urban schools, Wisconsin’s Cooperative Educational Service Agencies (CESAs) and school districts that want to apply for help, Kitchens said.

While drafting the bill, Kitchens has looked to Mississippi, which is often cited as a model by advocates of the science of reading curriculum. From 2013 to 2019, Mississippi fourth graders increased their reading scores on a national exam by 10 points after the state transformed its approach to reading instruction.

“I don’t know if (Mississippi) is the gold standard, but when you look at Mississippi, it’s the poorest state in the union, it has the highest percentage of minority students, so with all the disadvantages that they have, they’ve gone from last in reading to about where we are in the early grades,” Kitchens said. “I think what we come up with will have a lot of similarities there.”

Thomas McCarthy, executive director for the Office of the State Superintendent, said the plan will be successful if the Legislature and DPI can agree on what the core components will be. The most important aspect will be coaching and supporting current teachers, McCarthy said.

Other important pieces include making sure colleges change the way prospective teachers are taught and coming up with a new method of assessing third graders’ reading skills, McCarthy said.

Wisconsin slow to adopt sweeping reading changes

More than 30 states have already adopted laws or are moving towards requiring school districts to use the science of reading approach. But partisan gridlock in Wisconsin has kept the state from moving forward on a comprehensive reading plan for several years, despite third grade reading test scores remaining stagnant or falling.

“Reading scores have been dropping for 40 years,” Kitchens said.

Only 33.8 percent of third graders were proficient in reading on the most recent Wisconsin Forward Exam. Wisconsin’s achievement gap between Black and white fourth grade students in reading has often been the worst in the nation.

Previous reading-related bills brought forward by the GOP have been vetoed by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers. They included a 2021 bill that would have increased the number of times students were tested and asked schools to come up with intervention plans for students who scored poorly.

Evers also vetoed a similar 2022 bill. With both vetoes, the governor raised concerns about long-term sustainable funding.

Kitchens said he did not want to bring another bill forward this session that would get vetoed, so he has been working with the governor and DPI and the conversations have been encouraging.

“As far as (Evers) thinking on it, it seems he has moved towards realizing that we have to do something more about reading that didn’t seem to be there in the past,” Kitchens said.

McCarthy agreed, saying there have been more “open and vulnerable conversations between all the parties.”

“That is really what is going to move the needle on what our learners need instead of where the political winds are swirling on a particular day,” McCarthy said. “We all know this is an issue we can address if we put our cards on the table and talk this through.”

Evers could not be reached for comment.

Wisconsin is a local control state where districts choose their own curriculum. This bill could give DPI standards that could be enforced, McCarthy said.

McCarthy said superintendents in the state’s five largest school districts – Milwaukee, Madison, Racine, Green Bay and Kenosha – began to “bite off” the idea of science of literacy before the pandemic. Some districts have gotten further than others.

Madison public schools implemented science of literacy this year.

Changes would come at a time when schools need more funding

If approved, the massive change to reading would come at a time when schools are facing a shortage of people willing to work in education. In Milwaukee Public Schools alone there are more than 350 teacher vacancies.

McCarthy said $15 million is a good start to fund the reading program, but he hopes it doesn’t come at the detriment of other funding for schools.

“I don’t want to drop a bunch of money onto a dire need that pulls apart a gigantic hole somewhere else,” he said. “Otherwise, it’s just a shiny object districts are forced to chase. It has to be partnered with reliable revenue growth.”

Kitchens acknowledged the challenge – including that most reading coaches would likely come from the classroom. He said that’s why the reading changes would be rolled out over several years.

He also said this is a hard sell to his own Republican caucus.

“People want to beat up DPI and educators, so it will be a fine line getting this through the caucus and satisfying them,” Kitchens said. “But if we don’t have buy-in from the education community it won’t work.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.