Migrant workers played a key role in making Wisconsin a modern agricultural powerhouse. Seasonal workers who traveled from Mexico, and Texas-born people of Mexican descent, known as Tejanos, became a crucial part of Wisconsin’s agricultural workforce during and after World War II, setting the stage for a dairy industry that relies heavily on immigrants to this day.

As they found work in Wisconsin and elsewhere around the United States, Mexican-American and Mexican migrant workers often found that white farmers and food processors wanted their labor but often did not regard them as fellow citizens or fellow human beings. These attitudes have influenced the politics of immigration throughout the nation’s history, especially in the early 20th century when Wisconsin experienced its first significant wave of Mexican immigration.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Sergio M. González, a Marquette University professor of history and language who earned his Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, has conducted detailed research into the history of Mexican-Americans in Wisconsin, with an eye toward how this immigrant group has confronted labor abuses and racialized politics. González wrote the 2017 book Mexicans in Wisconsin, which explores specific periods and political and cultural facets of Wisconsin’s Mexican-American communities, from the arrival of “Los Primeros” in the 1920s to a broad wave of undocumented immigrants in the 1970s and ’80s.

In an Oct. 17, 2017 talk at the Wisconsin Historical Museum in Madison, González discussed a period running from the outbreak of World War II to the late 1960s that shaped the role of Wisconsin’s migrant workers and year-round Latin American residents in profound ways. The war ratcheted up pressure on Wisconsin agriculture to produce more food, and many of the migrant workers who stepped in found themselves facing abusive employers and substandard living conditions.

González began his talk, recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s “University Place,” with a story about a group of migrant-worker families who tried to go to a county-operated swimming pool in Waupun in 1949. A custodian at the pool, Seymour Patrick, barred the families, complaining that migrant workers didn’t speak English and saying that white parents didn’t want their children to play with Mexicans or Tejanos. The Fond du Lac County government and the League of Women Voters of Waupun pushed back, starting a local movement to address racial divides within the community.

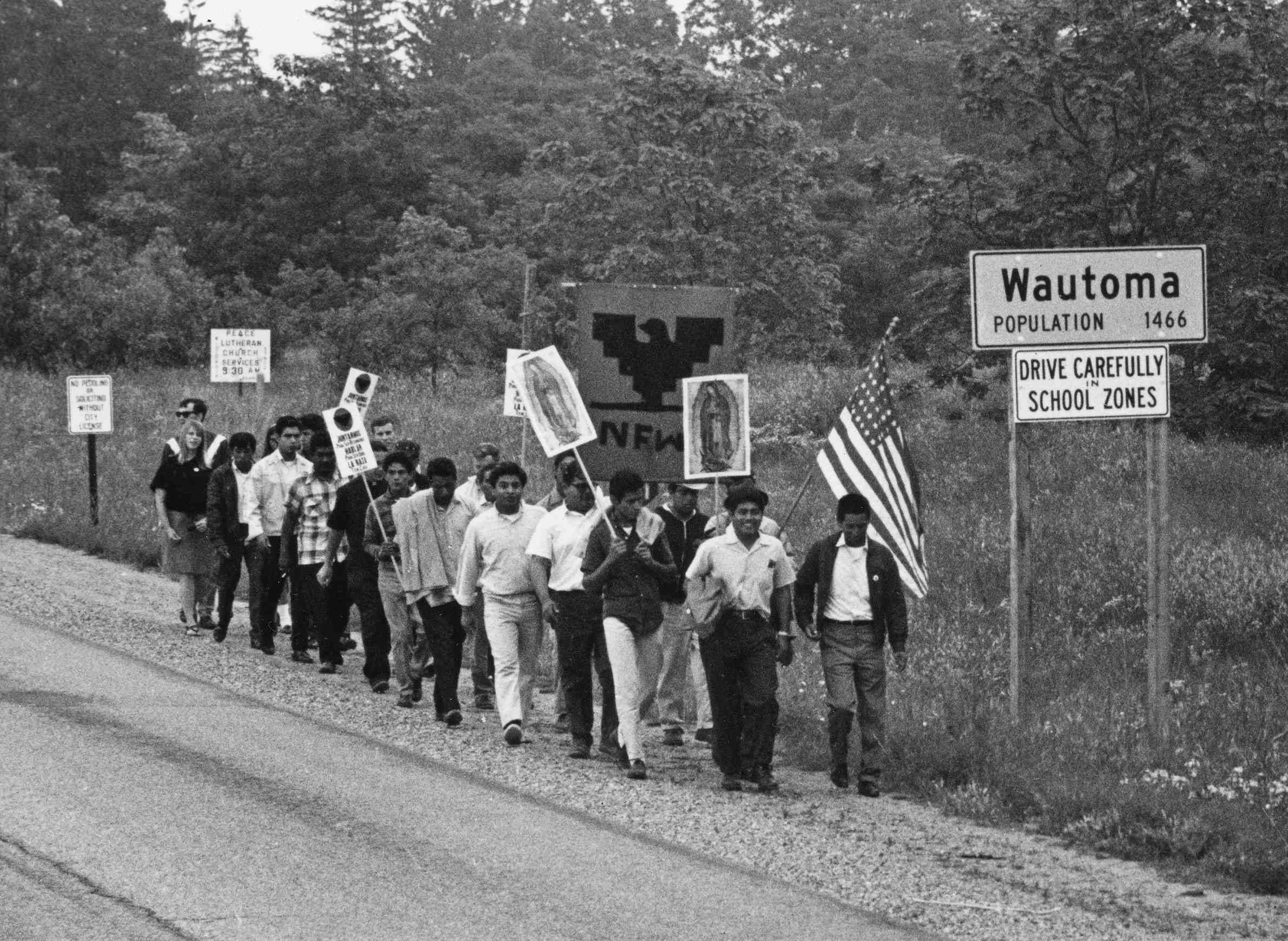

Despite this and similar efforts, some at the state-government level, real change came slowly, González said. State commissions on migrant labor conducted studies that managed to shed light on the challenges Latin-American workers and families in Wisconsin faced, but they often lacked the authority to actually make or enforce policies. Frustration with such efforts prompted workers to take more action on their own, which included forming unions and conducting marches to the state Capitol. These movements drew inspiration from major immigrant-labor leaders in California like Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez, and from the Chicano Movement of the 1960s.

González detailed policy efforts meant to help migrant workers, the emergence of an immigrant labor movement, and how Latin-American immigrant workers remain important to Wisconsin’s agricultural economy, but resentment and racism continue to make their situation precarious.

Key facts

- During the late 1920s, and throughout the 1930s, approximately 3,000 Tejanos, people of Mexican descent from Texas, came to Wisconsin annually to work seasonally on farms.

- Agricultural production in Wisconsin picked up as the United States enter World War II, as more Americans left home to serve the military and, at the same time, increasingly moved from rural to urban areas. These changes created a farmworker shortage, and the U.S. government created guest-worker programs to meet the need, allowing growers to bring in workers from Mexico, the Caribbean and even German prisoners of war to work their farms.

- The 1942 Mexican Farm Labor Agreement, also known as the Bracero program, brought hundreds of thousands of Mexican workers into the U.S., mostly California and southwestern states. About 4,800 of these guest workers came to Wisconsin during World War II. This program was supposed to guarantee workers transportation, food and the local minimum wage, as well as housing, health care and sanitation. However, these workers faced transportation delays on their way to Wisconsin, and ended up living in boxcars and receiving poor medical care. Some of these doctors would misdiagnose the workers — telling them, for instance, that bronchitis was just a bad cold — in order to keep them working. The Mexican government investigated these working conditions and the social circumstances Mexican nationals and Mexican-Americans faced in Wisconsin, and even temporarily blocked access to the state using the program when it found problems.

- In the immediate post-war years, Tejanos accounted for nearly 85 percent of migrant workers in Wisconsin. Throughout the 1950s, between 10 to 14,000 migrant laborers made their way from Texas to communities like Wautoma, Oconto, Rosendale, Lomira and Fox Lake every summer, helping the state become a top producer of canned of peas, sweet corn and beets.

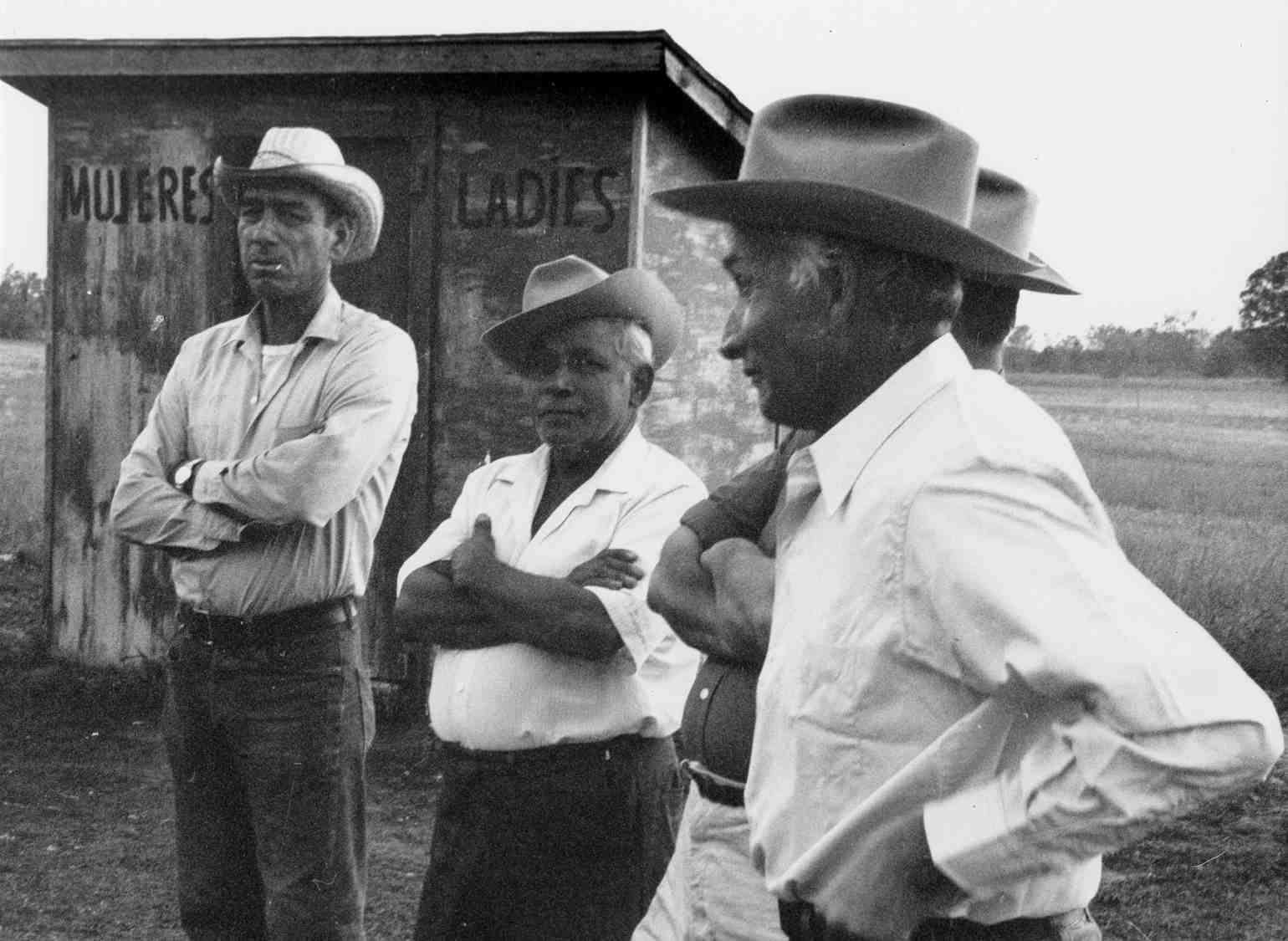

- During the post-World War II era, larger agricultural producers around the U.S., especially those who viewed guest workers with humanity and respect, often managed to provide housing that met at least minimal standards of ventilation and sanitation. But smaller farmers often provided workers housing that one researcher referred to as “hovels which defy description.” According to a 1948 report, one-third of the housing units provided for migratory families were unfit for human occupancy. State and federal laws gave migrants little recourse to address these conditions. At the same time, New Deal programs, including the National Labor Relations Act, the Fair Labor Standards Act and Social Security deliberately excluded migrant workers, including Tejanos who were U.S. citizens.

- State commissions throughout the 1940s and ’50s, including the Governor’s Commission on Human Rights in Wisconsin, tried to address rising tensions between Tejanos and white people in the state through education and research on the conditions migrant workers experienced. However, these bodies had no power to enforce civil-rights laws. The commission’s 1950 report “Migratory Agricultural Workers in Wisconsin: A Problem in Human Rights” detailed the work conditions and labor abuses employers inflicted upon migrant workers, and discussed these workers’ difficulties in assimilating into the community, as well as the lack of educational opportunities available to their children.

- Door County cherries have a troubled history when it comes to migrant workers. During the 1950s, growers in the county brought in migrant workers to pick and process tens of millions of pounds of cherries per season, providing them substandard, segregated housing and sometimes paying them less than half of what they’d contractually promised. African-American workers in Door County also faced abuses. Resort owners in the area claimed that African-Americans and Tejanos in the area drove business away — even though guest areas rarely went into resort areas — and businesses practiced open segregation in response.

- During the 1950s and ’60s, Portage, Waupaca, Adams, Waushara, Marquette, Green Lake and Wood counties in central Wisconsin relied every year on more than 10,000 Tejano migrant workers to plant, harvest, and process potatoes, lettuce, carrots, onions, cucumbers, peppers and sugar beets. These workers and their families faced discrimination and were often relegated to low social and economic status.

- People supporting migrant workers in Wisconsin — including prominent organizations like the Catholic Church and the Governor’s Commission on Human Rights — made both moral and business-driven arguments about treating migrants better. These supporters said exploitation reflected poorly on Wisconsin communities and that migrant workers should be treated as an economic asset. However, farmers and canners often turned a deaf ear and continued to provide low wages and poor housing.

- In the wake of the Governor’s Commission’s 1950 report, advocates in state government and religious groups continued to urge for better treatment of migrant workers, but they lacked real power to create or enforce policy. However, this situation began to change in 1960, when Gov. Gaylord Nelson created the Governor’s Committee on Migratory Labor, chaired by UW-Madison Economics Professor Elizabeth Brandeis Raushenbush. This group successfully lobbied for public funding for educational programs for migrant children, but its policy successes were piecemeal and didn’t manage to address systemic issues that relegated Tejanos to second-class citizenship status.

- The emergence in California of the National Farmworkers Association (later called the United Farm Workers) sparked a national conversation about working conditions in agriculture and the rights of farmworkers to unionize. Jesus Salas, a third-generation farmworker whose family settled in Wautoma, helped to lead a 1966 union organizing drive among migrants working in the cucumber industry in central Wisconsin. They called their union Obreros Unidos, or Workers United, and adopted the slogan of “La Raza Se Junta” or “The People Rise to the Cause.”

- In August 1966, about 5,000 Obreros Unidos members from across the state marched to Madison to draw attention to four key demands: a higher minimum wage, coverage under the state’s workers compensation laws, representation on the Wisconsin Governor’s Committee on Migratory Labor, and public sanitation facilities in Wautoma.

- The prominence of dairy in Wisconsin agriculture’s dramatic shift toward dairy has created a year-round need for a reliable labor force. As rural populations drop, the industry has come to rely heavily on immigrants, who make up some 80 percent of the workforce on Wisconsin’s dairy farms. A large percentage of those workers are undocumented. The Republican-led state Legislature’s efforts to crack down on “sanctuary cities” distressed both immigrant-rights groups and some dairy farmers, prompting large-scale protests at the state Capitol.

Key quotes

- On World War II’s effects on Wisconsin food production: “Following the expansive agricultural dive of World War II, the number of Wisconsin crops raised and harvested for canning leapt upward in the subsequent decades. Before the start of the war, individual farmers could harvest their own crops, and deliver them to canneries the following day. Throughout the 1950s however, farmers were responsible for hundreds of thousands of acres of field with peas, sweet corn, cucumbers for pickles, cherries, snap peas, lima beans, sugar beets and tomatoes. And who did these farmers turn to for migrant work? People from Texas. Growers and canners concentrated the recruitment efforts on these Texas-born, Mexican-American families, also known as Tejanos.”

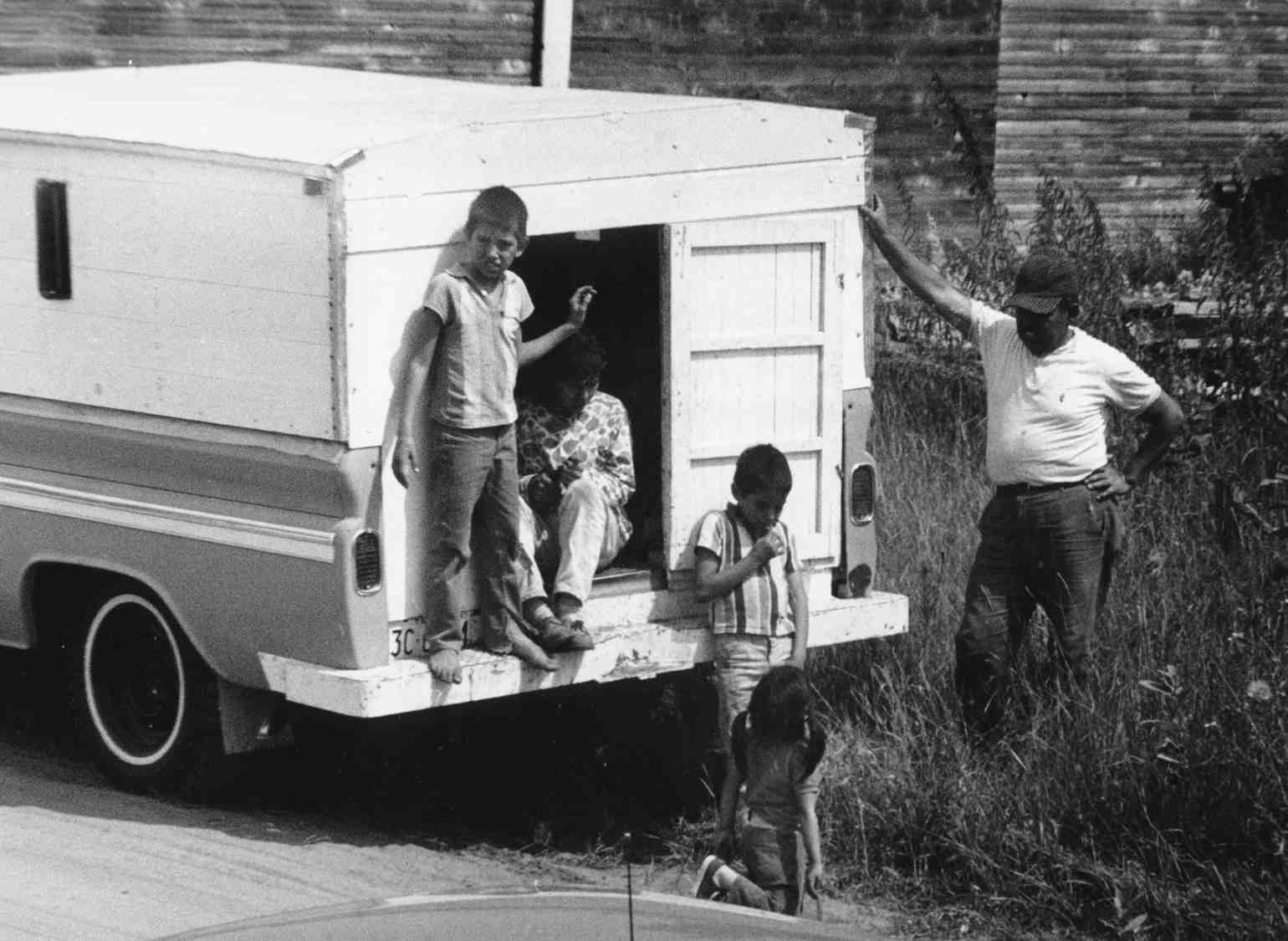

- On the makeup of migrant worker groups: “The migrant crews usually consisted of groups of families, ranging from 10 to 30 men, women, and children, who traveled by car, or by covered truck, or sometimes by uncovered truck. Nearly all workers that arrived from Texas came in family units, all of whom worked in the fields, including the children.”

- On the role of religion and government in migrant-labor disputes: “Throughout the 1950s, religious organizations and state commissions grappled with how best to integrate these migrants into the rest of the state. Wisconsin advocates argued that the exploitation of migrant families affected not only the migrants themselves, but also left what they called an irreparable scar on the moral character of the communities that received them.”

- On the social fabric of immigrant-labor organizing during the 1960s: “These union organizing drives were not simply led by the people who worked in the fields. They were completely family events … because migrant units were often consisted of an entire family. It was not just the mother or father working in the field, but it was often the grandmother, and the children who are also part of these organizing drives.”

- On the historic role of immigrant labor in Wisconsin agriculture: “Without Mexican laborers, documented or undocumented, Wisconsin’s dairy industry as well as meat packing, and food processing plants in rural parts of the state, would collapse. And so once again … workers of Mexican descent, brought to the state, are seen as an economic necessity, but they find themselves, find it impossible to exist and prosper in Wisconsin. Unlike those former Tejano migrants who traveled to Wisconsin every year growing and harvesting in the summer seasons, many of the people who are being targeted today, have lived in the state for decades. They’ve bought homes, their children attend schools and they have become vital members of their communities.”

A Mid-Century Turning Point For Migrant Farmworkers In Wisconsin was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.