Wisconsin author and farm historian Jerry Apps is concerned about water.

On a farm not far from the one he grew up in near the small Village of Wild Rose, Apps struck a match on the wall and lit a fire in an old wood stove, similar to the one his family used back in the 1930s.

“My dad would say in no uncertain terms, ‘Never curse the rain,’” Apps sang in his rich baritone voice, perfected by years of book tours and public speaking events.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The saying is also the title of his latest book in which he argues as a society we need to view water the way his father did 80 years ago. Water was precious back then in a home with no indoor plumbing. It had to be hauled by hand every Saturday to that wood stove for the once-a-week bath.

“My brothers were bathed, then it was my turn,” Apps mused, with a look of disbelief at his own recollection. “Same water. Then my mother, and finally my dad. We all bathed in the same water.”

The water was pulled from a deep well by a wind mill. With no electricity to power a pump, when the wind stopped blowing, it was a serious problem.

It’s one of Apps’ most vivid childhood memories.

“It was a hot, dreary, dry night,” Apps recalled. “You could hear for miles. There was no wind to break the sound. And there was just a mournful, mournful cry of cattle wanting water, needing water, and not getting any water. It was an orchestra of mournful sounds, that you did not want to hear, but you couldn’t avoid hearing.”

A few miles from the old farmstead was the Wild Rose grist mill, a building that is still standing, but no longer functioning. Water from the Pine River ground the feed for cattle. It also generated electricity for those fortunate enough to live in town.

“The people in the Village of Wild Rose had electricity, and the farm people, just a few miles out of town, did not. That created a tremendous rift,” Apps said, his breath steaming in the cold February morning.

Apps said he believes the urban rural rift still exists in America today, as evidenced in everything from attitudes to election results. And he said he believes it was partly created decades ago by who had running water and who didn’t.

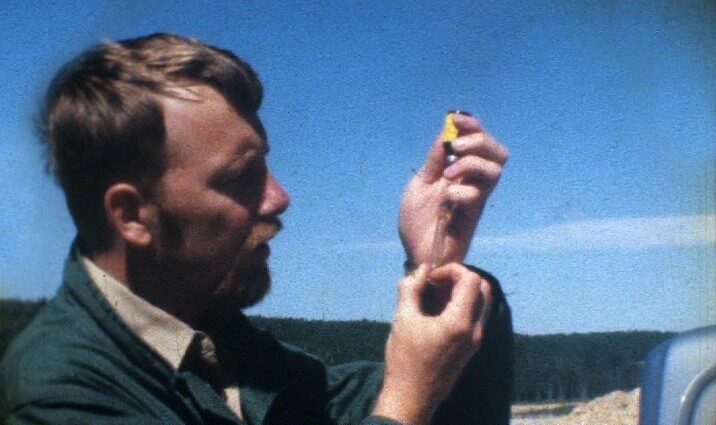

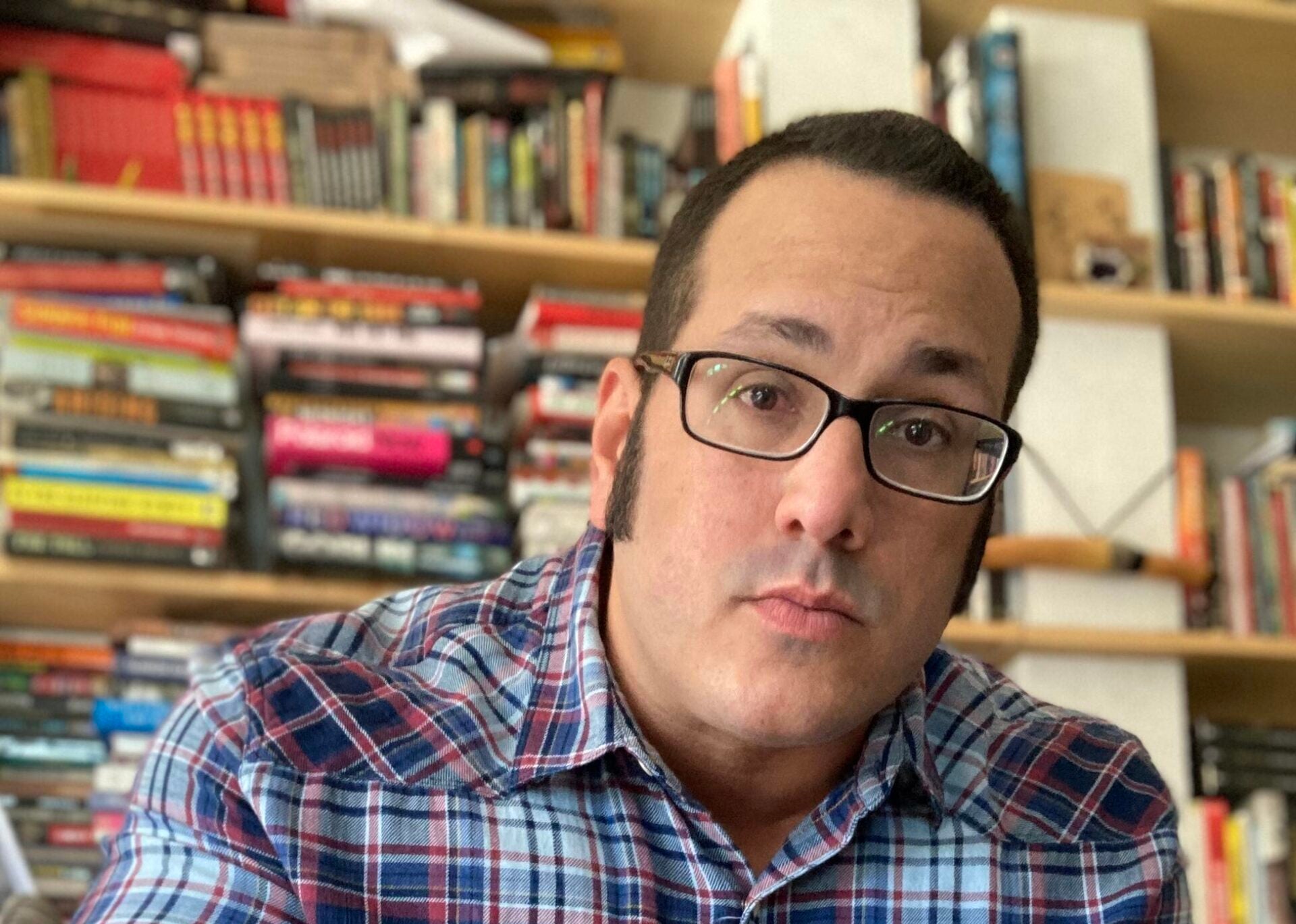

Jerry Apps speaking at Patterson Memorial Library in the Village of Wild Rose. Glen Moberg/WPR

“The idea of growing up in the country meant that you were a country hick. You had limited education, limited exposure to the finer things of life,” he said ruefully. “As kids, I was ashamed to have my friends from town come out to the farm because we had no indoor plumbing.”

That same February morning there was an overflow crowd at Patterson Memorial Library in the village that gathered to hear Apps share stories from the old times and read from his new book, “Never Curse the Rain: A Farm Boy’s Reflections on Water.”

“‘You have running water out there yet at that farm?’ My dad’s response was, ‘You bet we do! You grab up a pail and you run with it,’” Apps recalled to laughter.

The stories and the underlying message struck a chord with Janet Case, who grew up near Colby on a farm without electricity.

“I have a dear friend in Tucson,” Case said. “She speaks of the water level out there going down, down, each year, more and more. We can’t live without water.”

Childhood friends Fred Johannes and Oscar Cardenas also grew up on nearby farms without running water. Cardenas was born into a migrant worker family. They both used to take baths in washtubs in the barn and also believe clean water will soon be a big issue.

“We have an environmental problem,” Johannes said, reflecting on the threat posed by pesticide use of farm fields “One group makes money off of it, and the rest of us are suffering.”

“Someday, maybe I won’t see it; someday, water is going to be very expensive,” Cardenas said.

Over the years, Apps has seen how high capacity wells have changed the landscape in central Wisconsin.

“There are entire lakes that have dried up, disappeared,” Apps said. “People who own cottages on those lakes, when they bought their cottage, they had a lake for fishing and swimming and boating. And now they set looking at a pasture.”

And Apps has seen how climate change is affecting Alaska, where he has conducted writing workshops.

“One of the glaciers that I visited, it had receded like 3 miles in the last 20, 25 years,” Apps said, shaking his head. “That to me is an obvious piece of evidence that does not require a whole lot of scientific research. Just go there and look at it.”

Apps argues we now need the same reverence for water that his father had in the 1930s, and that America’s original inhabitants had before that.

“Not only should we be concerned about our water in the year or two ahead, but as the Native Americans say, ‘We must consider seven generations ahead,”‘ Apps said, adding that future generations could learn and benefit from the example of his past.

This story is part of a yearlong reporting project at WPR called State of Change: Water, Food, and the Future of Wisconsin. Find stories on Morning Edition, All Things Considered, The Ideas Network and online.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.