In Wisconsin, it’s estimated that about 120,000 people have Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia. Those numbers could triple by 2050 because of the aging Baby Boomer population, experts say.

While many dementia caregivers currently face major challenges, this population shift has many looking at what it will take to meet their needs in the important years to come.

It was Nov. 11, 2010, and Jennifer Jaqua’s husband, Jim, had just rolled through a stop sign near their home in the village of Mount Horeb. He was pulled over by police.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“And instead of sitting in the car and waiting for the officer to come up and say, ‘Sir, did you know you just rolled that stop sign?’ He got out of the car and approached the officer,” Jaqua said. “And then they said, ‘You need to get back into your car,’ and he refused. And he said, ‘I didn’t do anything wrong,’ and got very defensive. So, they proceeded to handcuff him and throw him in the back of the squad.”

Jennifer said that she had noticed Jim’s behavior had changed recently, but having her previously law-abiding husband in handcuffs was a real turning point. It was about a month later when he was diagnosed.

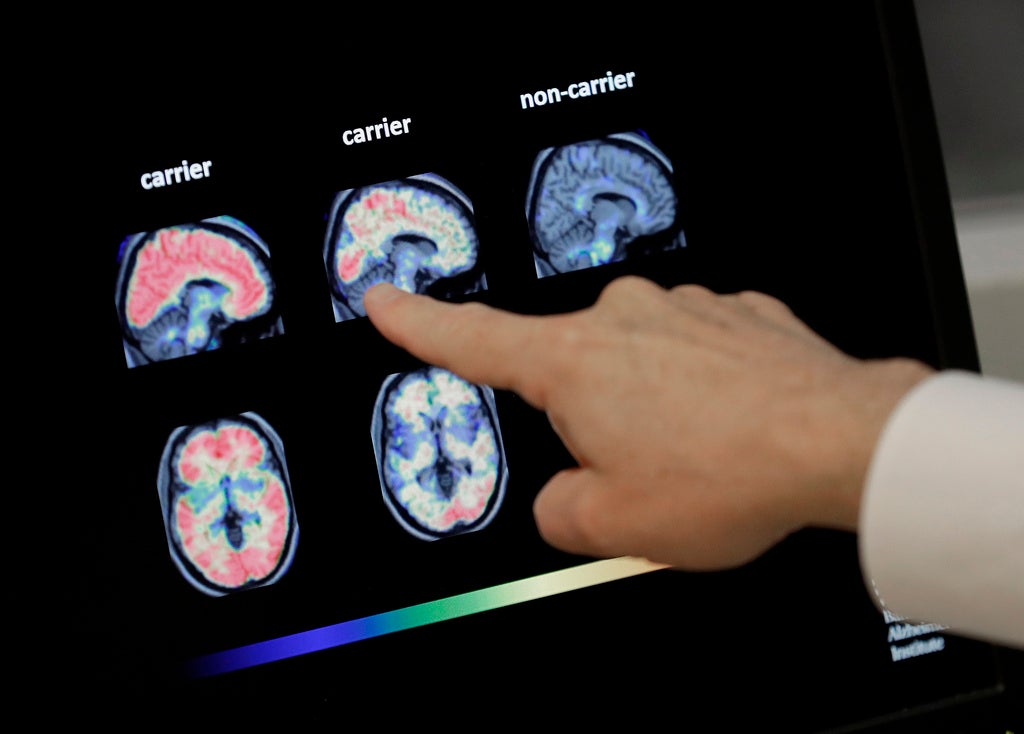

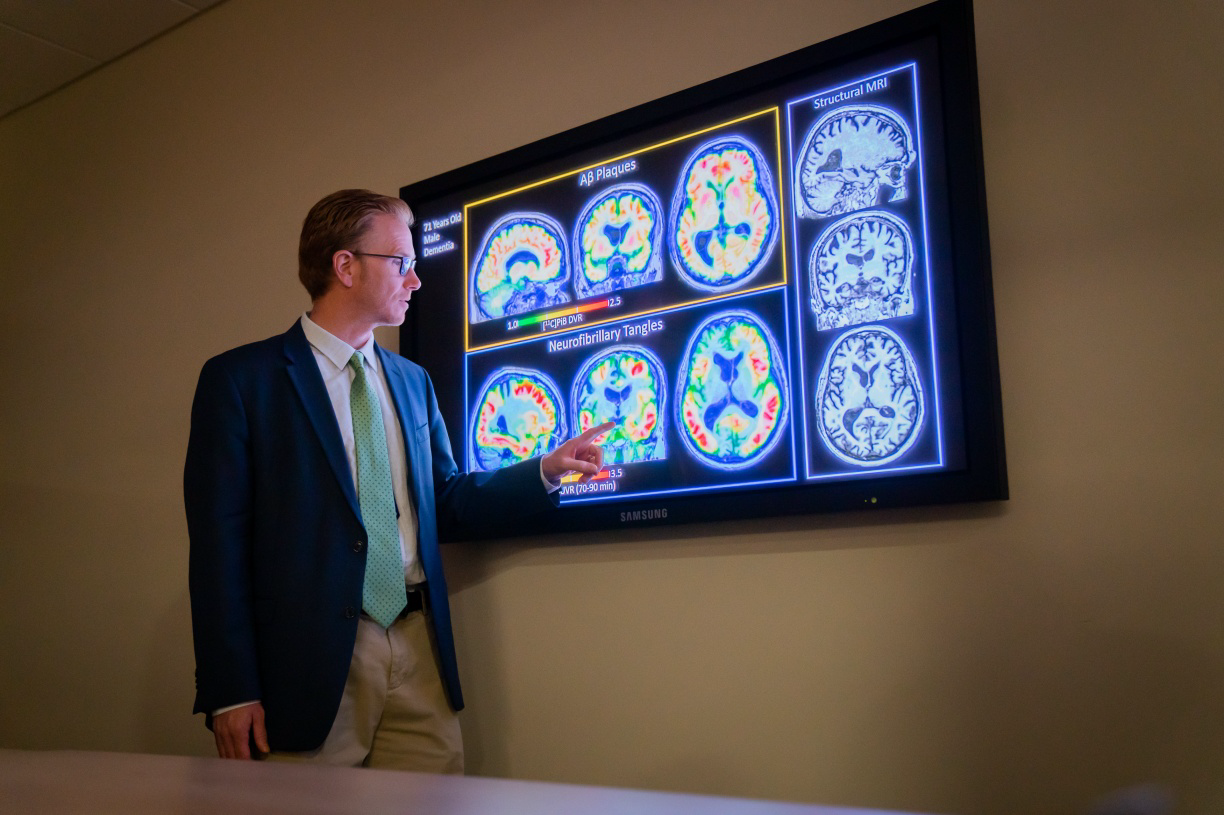

“It’s the deterioration of his frontal lobe of his brain and temporal and that frontal lobe, of course, is what controls your executive function and your decision making, your insight, judgment, your personality,” she said.

The disease has caused Jim’s personality to change. So much so, that Jennifer said today she’s married to a very different man. The new Jim can be confrontational and inappropriate. And at least once a week, she said he has a huge meltdown.

Because of his dementia, Jim can no longer work or drive a car. He lives at home while Jennifer works full time and coordinates his care.

Rob Gundermann of the Alzheimer’s and Dementia Alliance of Wisconsin, said the costs for care can be steep.

“The way you really save money with dementia is to keep people at home. If you put them into a nursing home, the average nursing home cost in Wisconsin is $93,000 a year right now,” she said.

Wisconsin’s aging population is set to explode and the costs could skyrocket. So, keeping dementia patients in their homes for as long as possible is necessary, Gundermann said.

By 2015, officials with the state Department of Health Services said Wisconsin will have over 900,000 people who are 65 years and older.

“That is roughly 117,000 more than were 65 in 2010. So, in five years, we’re gaining 117,000 … 65 year olds,” said DHS Secretary Kitty Rhoades.

Rhoades said connecting people with resources to help keep them in their homes and safe for longer is the only way the state will be able to afford the population boom.

But she said there are challenges in rural areas of Wisconsin where public transportation and services can be lacking. Jennifer Jaqua actually packed up and moved her family from Mount Horeb to nearby Madison.

“(We moved) because it was too difficult for me to get him and out to activities. You know, Madison is rich with resources and things that are very appropriate and meaningful that Jim likes to participate in, but I just couldn’t get him to everything,” she said.

In Madison, a paratransit bus picks him up at the door. While Jennifer works, Jim is able to go to adult day care three times a week, as well as other dementia specific programs and physical therapy.

Gundermann said those are resources that really pay off.

“Being able to get to say an adult day care one day a week paid for then that enables the caregiver to not burn out and caregiver burnout is one of the things that will trigger sending someone into a nursing home.”

Jaqua said with help, she hopes to keep her 61-year-old husband at home for as long as possible.

“Because of the access to services and transportation … I don’t have to do it all,” she said.

She said not having to do it all allows her to keep her job and that provides her with very important and necessary time away.

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth in a six-part series on aging and elder care in Wisconsin.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.