More than 40 years ago, these exiles left their lives in Cuba. They’ve since established roots in Wisconsin.

By: Maureen McCollum, Omar Granados

Episodio 1: traducción al español

It’s Oktoberfest weekend in La Crosse. The small city along the Mississippi River is bursting with energy. People have made their way from the parade to the festival grounds, where you don’t have to be German to show off your finest lederhosen, pretzel necklaces and beer steins.

In between polka sets, some local bands take the stage — like Mr. Blink.

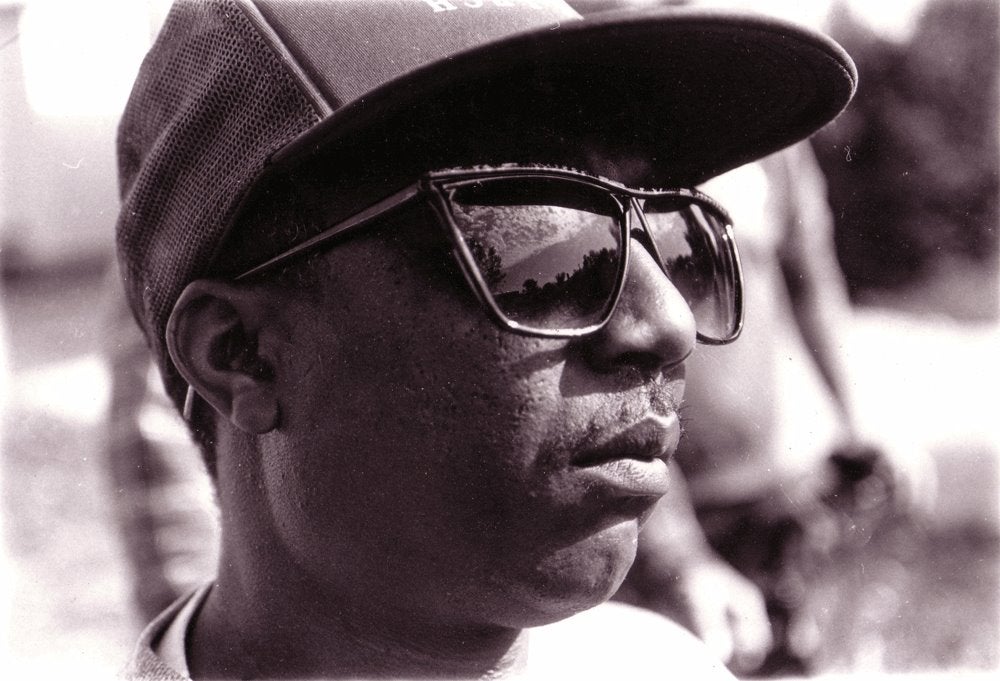

Mr. Blink has been a staple of the La Crosse music scene for more than 30 years. For a lot of that time, Enrique Moré has played percussion with the group, energizing songs with congas and the tambourine.

“I always play with Mr. Blink,” Moré said. “Because I like to play music too much.”

If you’ve seen live music in La Crosse any time over the last 40 years, you’ve likely seen Moré play. Outside of Mr. Blink, the 69-year-old has filled in with different bands, played open mic nights and showed up to impromptu jams.

For many years, Moré worked at the media center at Gundersen Health System in La Crosse. He has roots in the city. His circle of friends goes beyond the music scene.

Wisconsin is his home.

But it didn’t feel much like home when he first got here — when he was one of the few Cubans to settle in La Crosse after arriving in 1980.

Moré refers to himself as “a fly in the milk” — a phrase used in Cuba that means being the only Black person in a sea of white people.

He came to the United States during the Mariel Boatlift. For five months in 1980, the Cuban government opened its borders at the Port of Mariel. During that time, nearly 125,000 residents left the island for the U.S.

Moré was one of the almost 15,000 migrants who temporarily lived at Fort McCoy, in the small western Wisconsin town of Sparta.

For many years, when Moré was asked about his experience — what it was like to leave his life in Cuba; to be sent to live on a military base in a completely new country; to be surrounded by strangers, only some of whom speak your language; unable to leave on your own — he would say: “The past is the past, I don’t like talking about the past.”

But now, he’s opening up.

Moré grew up in Havana, Cuba. When he was young, he wanted to play violin and flute, but people steered him toward percussion; specifically, the timpani.

Music was in his blood. Moré said he’s related to the famous Cuban musician Benny Moré.

Outside of music, he played soccer. He was a good student. Moré was the oldest child, and he was close with his family.

“I had a very good life in Cuba,” Moré said. “My mother was very good.”

And then in 1959, the Cuban revolution took place and Fidel Castro rose to power.

Moré was 6 years old at the time. As he grew, he saw the revolution affect nearly every part of his life. He didn’t always like what he saw.

Moré had been speaking out against Castro’s communist government. He had a few reasons. For example, he said the Cuban government took away a home that had been gifted to him. And then there was an incident involving beer.

At this time in Cuba,if you bought food or drinks at a restaurant, you had to use rations. Sometimes, it was mandatory to get food with your alcohol. Moré was at a restaurant with his friends and just wanted to drink beer. So he traded other customers his fish rations in exchange for their beer rations.

The restaurant manager didn’t like that tactic. Moré and the manager got into an argument, catching the attention of the police.

In the fallout of the beer exchange — and for criticizing Castro — Moré ended up in jail. He said he was incarcerated for one year, six months and one day.

This is where things could have gone very differently for Moré.

If the following series of events didn’t happen, it’s likely his life would be much different. He would have never ended up in Wisconsin, never established roots in La Crosse and never played with Mr. Blink on stage at Oktoberfest.

The Peruvian Embassy break

When Moré was in his mid-20s sitting in prison in 1980, a group of people hundreds of miles away stormed the Peruvian Embassy in Havana, demanding asylum so they could leave Cuba. About 10,000 people eventually showed up at the embassy and wanted to leave, including Moré’s brother.

Reacting to the embassy breach, U.S. President Jimmy Carter agreed to take in 3,500 refugees from the Peruvian Embassy — a move that angered Castro.

The decision came at the height of the Cold War, a period of time when tensions were high between the U.S. and the Soviet Union and its allies, which included Cuba.

On April 20, 1980, Castro opened the borders at the Port of Mariel and told people in the U.S. that Cuban Americans could pick up their relatives on the island. This marked the beginning of the Mariel Boatlift, a period in which 125,000 Cuban exiles boarded boats bound for Florida from April to October 1980.

Then, Castro decided to open the island’s prisons and psychiatric hospitals. Anumber of Cuban spies also entered the U.S. via Mariel.

Moré caught wind of Carter’s message welcoming Cuban refugees while in prison. It inspired him to leave.

But leaving wasn’t simple. As Moré made his way to the Port of Mariel, he was met with backlash from fellow Cubans who considered him a traitor or “escoria” — the Spanish word for “scum.” Some threw bottles and screamed taunts.

Once he arrived at the port, Moré boarded a boat with 11 other people. The trip across the Florida Straits to Key West, Florida, was treacherous.

“It was a bad, bad, bad weather. Oh, yeah. Bad weather,” Moré recalled, remembering the massive waves. “A lot of people didn’t make it. Because you fall down, there’s no time to (come up).”

Moré said his boat landed in Key West at 2:45 p.m. on June 2, 1980.

Luckily, everyone on his boat made it safely to Florida. But that wasn’t the case for many other Cubans making the journey. Some fell overboard because of the waves, or because they were allegedly pushed overboard by an enemy, Moré said.

The details are a little fuzzy on what happened next. As Moré got off the boat, he had to navigate a somewhat chaotic scene where he was processed by volunteers and U.S. government officials.

He said the captain of the boat was going to help him find a sponsor. Moré came across someone handing out apples and using them as a religious offering. He was drawn in. But in that moment, he was separated from the captain and lost his opportunity to move in with a sponsor, to settle with a family in Florida.

Instead, later that day, Moré said he boarded a plane in the middle of the night to fly to Fort McCoy in Sparta. He arrived on June 3, becoming one of the nearly 15,000 Cuban refugees to go to Fort McCoy in 1980.

From Cuba to Wisconsin

You may be wondering why a bunch of Cuban refugees in southern Florida were suddenly being flown to Wisconsin.

To put it simply: There wasn’t enough space for all the refugees in cities like Key West and Miami.

The U.S. government had to find a place to keep people temporarily before they found permanent homes with families or sponsors, said Omar Granados, an associate professor of Spanish and Latin American studies at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and co-host of “Uprooted.”

Fort McCoy is an Army Reserve and National Guard training base, which had been prepared for the arrival of thousands of Cuban refugees on extremely short notice by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. It was the last of four camps opened to house Mariel refugees.

The camp at Fort McCoy was set up with additional police and wire fencing than it had previously because of riots that happened in another Cuban refugee resettlement center, Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, Granados said.

According to NPR archival audiofrom 1980, officials of relief agencies working at Fort Chaffee said the main reason for rioting by Cuban refugees being held there was boredom. The exiles anxiously sat and waited with little to do until they could be relocated.

About 90 percent of the Cuban refugees at Fort McCoy were male. The majority of those exiles were between age 25 and 35, lacked professional experience and weren’t fluent in English, Granados said.

While living at Fort McCoy, Moré worked in the visitor center, and he said he genuinely enjoyed the food there. He played music and tried to have fun passing the time while living in the barracks.

But it could be scary at times, he said, since there were assaults, thefts and fights. Moré doesn’t like to go into details about his time at Fort McCoy.

“I don’t want to even remember,” he said. His tone shifted, becoming solemn. “This was a Wild West. Yeah, the Wild West.”

The sooner Moré found a sponsor — someone who vouched for a refugee and help them settle into new communities — the sooner he could get out.

Moré, at age 27, found a sponsor — someone he still considers a mother figure — and left Fort McCoy for La Crosse after three months.

Over the decades, he’s formed strong relationships with people in La Crosse. He’s found family within the city’s music scene, especially with his chosen brothers and sister in Mr. Blink.

But settling down in the Midwest has been difficult for Moréand many of the other Mariel refugees who came to the U.S.

While Carter initially accepted Cubans with “an open heart and open arms,” they weren’t necessarily welcomed in their communities — in La Crosse and Sparta and even down in Florida.

Many of these new refugees were young, Black men and had been labeled criminals by the Cuban government.

In its effort to build the perfect socialist society, the Cuban government, particularly in the 1970s, was incredibly strict about young people’s behaviorand anything that could affect their ideology, Granados said. Cuban police had an extra eye on the country’s youth.

One of those policed behaviors included smoking marijuana — which is what got Armando Rodriguez in trouble.

Rodriguez was just 16 years old when he arrived at Fort McCoy in 1980. He has lived in Madison on and off since then.

In Havana, he was sentenced to three and a half years in juvenile detention for smoking a joint.

“I was on a corner smoking marijuana with some friends of mine and the police came and picked us up. And they sent us to a juvenile prison,” he said. “We didn’t have a lot of marijuana, it was just a joint … After that day, I went many years without smoking marijuana because every time I smoke marijuana, I am reminded of the separation of my family. Today I don’t smoke.”

As the Mariel Boatlift was underway, Rodriguez was sitting in juvenile detention. Cuban officials asked him if he wanted to go to the U.S. At first, he said no.

But then, he was told his brother had left for the U.S., so he decided to make the journey.

For five months, Rodriguez stayed at the Fort McCoy military base, far from the only world he knew back in Havana. He started looking for his brother, Guillermo Rodriguez. He wanted to see him, hoping to feel some sort of connection to home.

But his brother wasn’t at Fort McCoy. It was another Guillermo Rodriguez.

“They told me that my brother had left for the United States. So, I said, ‘Well, I’m leaving!’ Then when I got here, they gave me my brother’s name, but my dad has the same name. Then I realized that it was my dad who had come, that it wasn’t my brother. My brother had stayed in Cuba, and today he is in Cuba,” Rodriguez explained.

Rodriguez uprooted his life, mostly because he thought his brother had moved to the U.S.

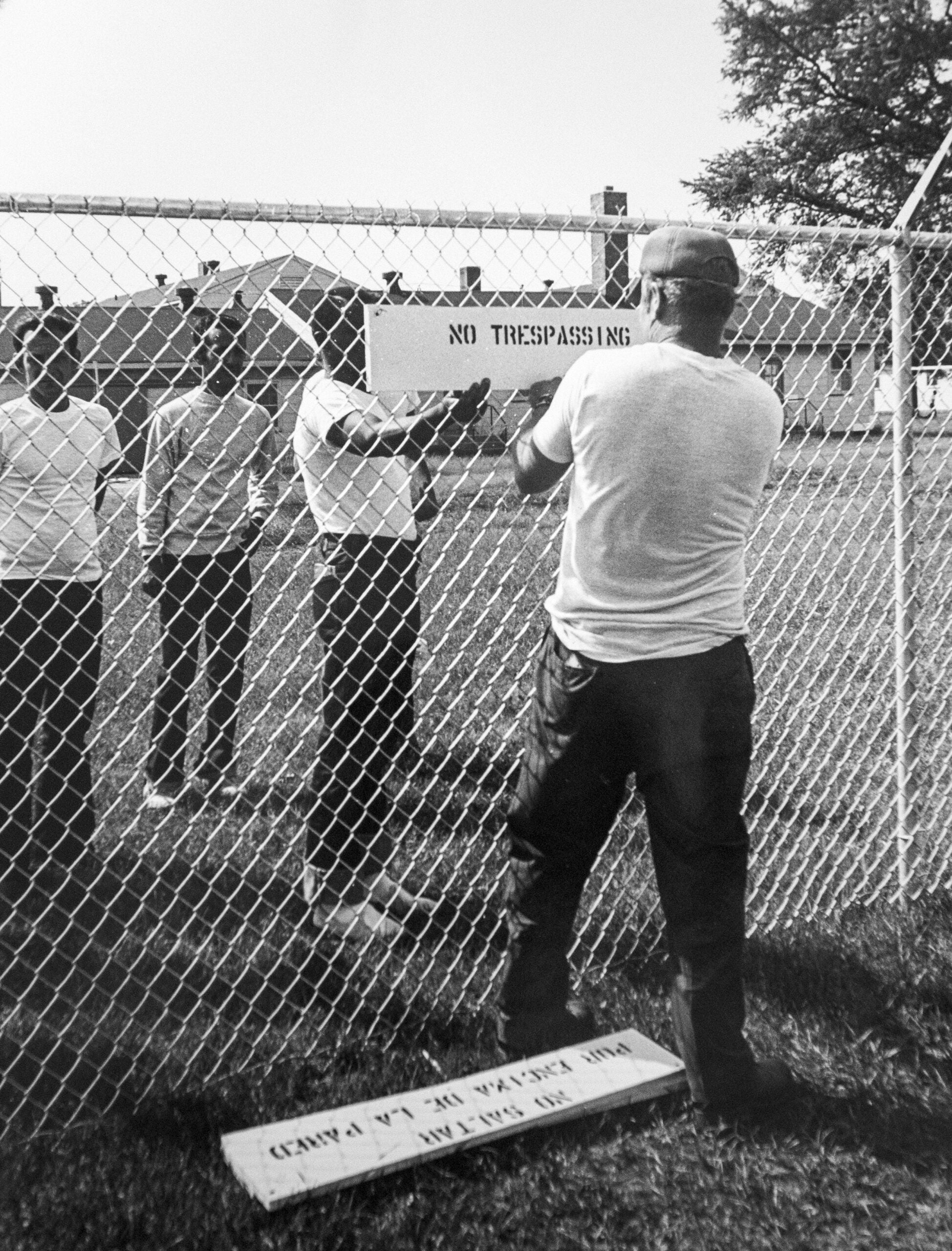

Rodriguez said he hadn’t spoken to his father in years. But despite their estrangement, once the father and son reconnected at Fort McCoy, they developed a daily routine. They’d leave their separate barracks and meet at a barbed wire fence to talk.These tall, barbed wire fences kept kids separate from the adults who were also living at the military base in Sparta. Government officials wanted to protect the children, but Rodriguez said it felt like a prison.

The two never saw each other again after leaving Fort McCoy. Rodriguez’s father, Guillermo Hernandez Rodriguez, was sent to New Jersey to live with a sponsor and has since died.

Other than the meetings with his father, Rodriguez doesn’t share many details about what he encountered at Fort McCoy. But other minors have written accounts of their experiences at the military base, which for some included sexual assault, stabbings and theft.

‘Encontré a mi padre’

At Satori Arts Gallery in La Crosse, Rodriguez looks through a stack of papers.

He’s not a 16-year-old trying to survive at Fort McCoy anymore. He’s in his 50s and works in Madison.

The documents are a list of every single Cuban refugee who came through Fort McCoy. And they’re blowing Rodriguez’s mind.

In the midst of his search, Rodriguez says, “I found my father.”

Most Cubans who left the base were like Guillermo Rodriguez —they left Wisconsin after connecting with family or finding sponsors.

But some people, like Armando Rodriguez and Moré, have remained in southern Wisconsin in places such as La Crosse, Sparta and Madison. There are hundreds of Cuban refugees in Wisconsin who have built lives as bus drivers, fathers and musicians. They’re mostly in their 60s. Many are unemployed without health insurance.

They say all they want is to go back to Cuba. But they can’t, because of documentation errors and criminal records.

“I have never been able to visit Cuba. I would like to visit Cuba,” Rodriguez said. “I am not allowed; and if I go, I can’t come back. I am in the same situation as everyone who has committed a crime.”

In the next episode of “Uprooted”: How the Cuban revolution in 1959 led to thousands of Cubans coming to the U.S. and Wisconsin in 1980 as part of the Mariel Boatlift. We’ll also learn what childhood was like in Cuba for two friends who now live together in La Crosse.

Editor’s note: WPR’s Alyssa Allemand contributed to this report.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.