The Wisconsin Supreme Court weighed arguments Thursday about whether to remove the embattled former chair of the Wisconsin Natural Resources Board who refused to step down at the end of his term last year.

Wisconsin Attorney General Josh Kaul filed a lawsuit in the summer seeking to remove Wausau dentist and businessman Dr. Fred Prehn from the board after his term expired in May. In 2015, former Republican Gov. Scott Walker appointed Prehn to a six-year term.

Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, appointed Sandy Naas and Sharon Adams to the board in April to fill vacancies left by members whose terms expired, including Prehn. His decision to stay on the board blocked Naas from taking a seat.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Prehn has argued a 1964 decision by the Wisconsin Supreme Court allows him to remain on the board until the Republican-controlled Senate confirms his successor. In the case, Thompson v. Gibson, the court allowed a state auditor to remain in his post because a replacement wasn’t confirmed.

A Dane County judge ruled in favor of Prehn in September, and Kaul asked the state Supreme Court to hear the case.

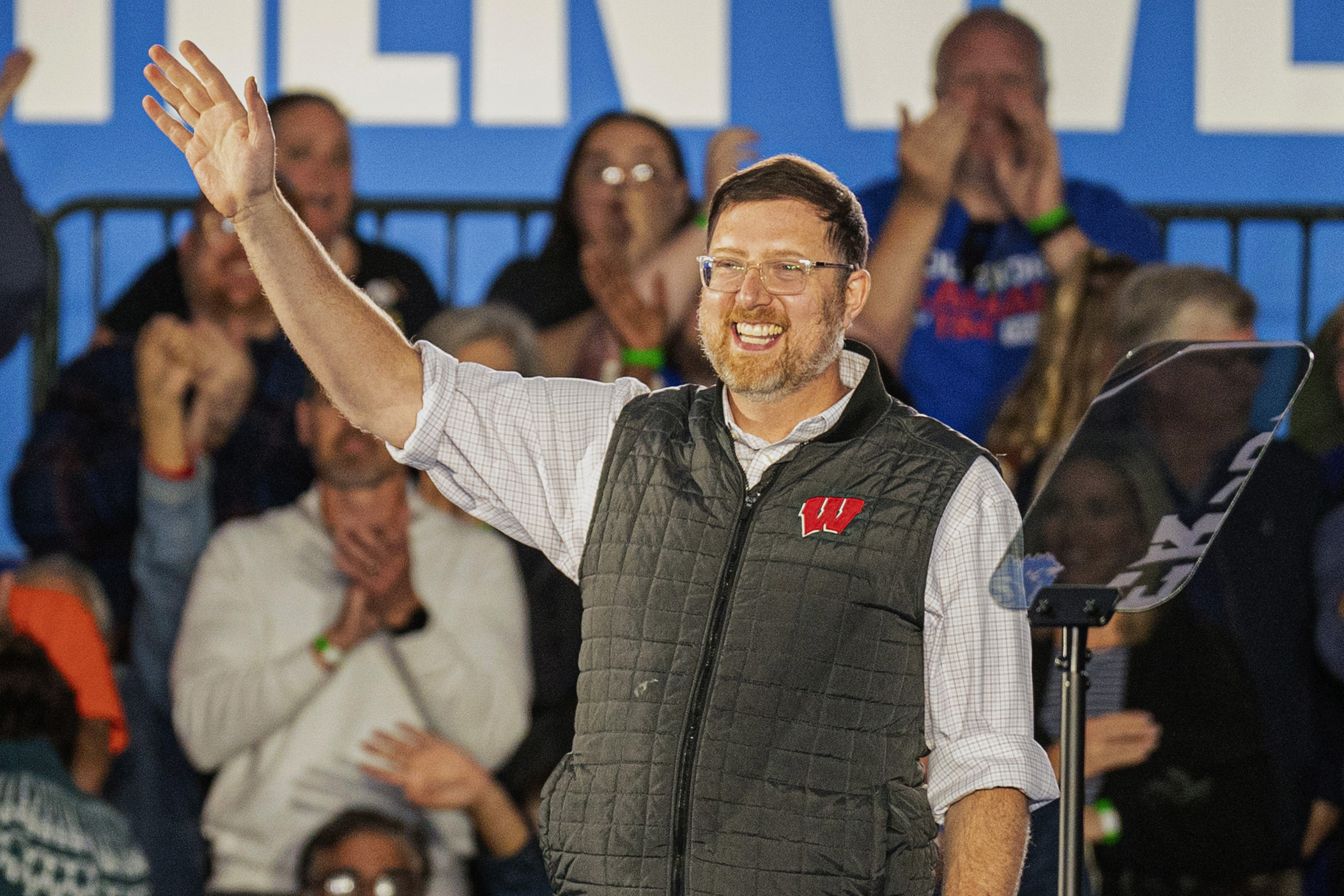

Wisconsin Assistant Attorney General Gabe Johnson-Karp argued the term for board members doesn’t include a holdover period. He argued a vacancy arose on the board at the expiration of Prehn’s term.

“He has no authority to be in office right now,” Johnson-Karp said.

Justice Rebecca Bradley disputed that argument.

“I searched the statutes and I don’t find any declaration by the Legislature in the statutes that upon expiration of an appointed term that a vacancy is created,” Bradley said.

Justice Pat Roggensack said the only reason the issue is being debated is that the governor appointed someone else — Naas — to serve on the board.

“That’s the only reason we’re fussing, but the governor can’t really make an appointment into a position that’s not vacant,” Roggensack said.

In the view of lawmakers and Prehn, Johnson-Karp argued the Legislature could stall the next appointment as long as they choose under the law. He urged the court to overrule the part of the Thompson decision that said the expiration of a fixed term does not create a vacancy.

He also added that state officers like Prehn who are appointed by the governor and serve with consent of the Senate can be removed by the governor at any time for cause or at the pleasure of the governor. He argued Prehn could be removed for any reason after the expiration of his term, adding that lawmakers can’t encroach on the governor’s power to remove him.

Justice Brian Hagedorn, who has been a swing vote on the court, appeared to question the governor’s authority to remove Prehn.

“If you look at some of the early laws that were adopted, governor’s powers were very, very limited,” Hagedorn said. “The very first Board of Regents that was enacted was appointed entirely by the Legislature. The governor had very little authority in relation to that.”

Prehn’s attorney, Mark Maciolek, also disputed Evers’ authority, saying holdovers are protected from removal. He also said the fixed term protects those holding office rather than limiting their service, saying there’s no limit to the number of terms an appointee could serve.

Maciolek said the governor could not make any provisional appointments if someone, like Prehn, chooses to hold over in their seat “because there’s no vacancy.”

Justice Jill Karofsky said there’s nothing in the statute that explicitly allows him to remain in his seat. Justice Rebecca Dallet argued that could essentially lead to lifetime appointments, creating broad implications for state agencies and boards.

“All they have to do is just stay put till the end of their life,” Dallet said.

Justice Rebecca Bradley noted people have held over in positions before under both Republican and Democratic governors, the longest of which served four more years.

Justice Ann Walsh Bradley said the Thompson decision creates an unworkable situation that undermines the separation of powers between the governor and Legislature.

The Legislature’s attorney, Ryan Walsh, argued this isn’t the first time the Senate hasn’t held a hearing on the governor’s nominee, adding lawmakers have confirmed more than 40 of Evers’ nominees.

“There are times where there are impasses between governors and legislatures, and they often work them out, and sometimes they don’t,” Walsh said. “The government continues to work as it is working now, which is part of the reason there is a holdover rule.”

The court is likely to issue a ruling by the end of its current session in June.

If the high court rules in Prehn’s favor, he could remain on the board for years if Republican lawmakers fail to hold a hearing. The Senate has refused or delayed confirmation of Evers’ appointees, including former Health Secretary Andrea Palm and Transportation Secretary Craig Thompson. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported more than 100 appointments by Evers were still awaiting confirmation as of the fall.

The board’s Walker-era appointees hold a 4-3 majority. The body has become the focus of unlikely power struggles. In the past year, the NRB has weighed contentious wildlife and environmental regulations surrounding wolf management and so-called forever chemicals known as PFAS.

Last month, the board reached a split decision on proposed standards to regulate PFAS in groundwater, causing the regulation to fail.

In August, the board voted 5-2 to set a quota of 300 wolves for the fall’s wolf hunt that was put on hold by a court ruling and later canceled after a federal judge restored protections under the Endangered Species Act. Board member Sharon Adams later clarified she never intended to vote for the quota, which means the board was split 4-3 between Walker and Evers appointees.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.